Question

The function \(f\,{\text{: }}\mathbb{Z} \to \mathbb{Z}\) is defined by \(f\left( n \right) = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n}\).

a.Prove that \(f \circ f\) is the identity function.[6]

b.i.Show that \(f\) is injective.[2]

b.ii.Show that \(f\) is surjective.[1]

▶️Answer/Explanation

Markscheme

METHOD 1

\(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} + {\left( { – 1} \right)^{n + {{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}}\) M1A1

\( = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} \times {\left( { – 1} \right)^{{{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}}\) (A1)

considering \({\left( { – 1} \right)^n}\) for even and odd \(n\) M1

if \(n\) is odd, \({\left( { – 1} \right)^n} = – 1\) and if \(n\) is even, \({\left( { – 1} \right)^n} = 1\) and so \({\left( { – 1} \right)^{ \pm 1}} = – 1\) A1

\( = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} – {\left( { – 1} \right)^n}\) A1

= \(n\) and so \(f \circ f\) is the identity function AG

METHOD 2

\(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} + {\left( { – 1} \right)^{n + {{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}}\) M1A1

\( = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} \times {\left( { – 1} \right)^{{{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}}\) (A1)

\( = n + {\left( { – 1} \right)^n} \times \left( {1 + {{\left( { – 1} \right)}^{{{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}}} \right)\) M1

\({\left( { – 1} \right)^{ \pm 1}} = – 1\) R1

\(1 + {\left( { – 1} \right)^{{{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}}} = 0\) A1

\(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = n\) and so \(f \circ f\) is the identity function AG

METHOD 3

\(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = f\left( {n + {{\left( { – 1} \right)}^n}} \right)\) M1

considering even and odd \(n\) M1

if \(n\) is even, \(f\left( n \right) = n + 1\) which is odd A1

so \(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = f\left( {n + 1} \right) = \left( {n + 1} \right) – 1 = n\) A1

if \(n\) is odd, \(f\left( n \right) = n – 1\) which is even A1

so \(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = f\left( {n – 1} \right) = \left( {n – 1} \right) + 1 = n\) A1

\(\left( {f \circ f} \right)\left( n \right) = n\) in both cases

hence \(f \circ f\) is the identity function AG

[6 marks]

suppose \(f\left( n \right) = f\left( m \right)\) M1

applying \(f\) to both sides \( \Rightarrow n = m\) R1

hence \(f\) is injective AG

[2 marks]

\(m = f\left( n \right)\) has solution \(n = f\left( m \right)\) R1

hence surjective AG

[1 mark]

Examiners report

[N/A]

[N/A]

[N/A]

Question

The set \(S\) is defined as the set of real numbers greater than 1.

The binary operation \( * \) is defined on \(S\) by \(x * y = (x – 1)(y – 1) + 1\) for all \(x,{\text{ }}y \in S\).

Let \(a \in S\).

a.Show that \(x * y \in S\) for all \(x,{\text{ }}y \in S\).[2]

b.i.Show that the operation \( * \) on the set \(S\) is commutative.[2]

b.ii.Show that the operation \( * \) on the set \(S\) is associative.[5]

c.Show that 2 is the identity element.[2]

d.Show that each element \(a \in S\) has an inverse.[3]

▶️Answer/Explanation

Markscheme

\(x,{\text{ }}y > 1 \Rightarrow (x – 1)(y – 1) > 0\) M1

\((x – 1)(y – 1) + 1 > 1\) A1

so \(x * y \in S\) for all \(x,{\text{ }}y \in S\) AG

[2 marks]

\(x * y = (x – 1)(y – 1) + 1 = (y – 1)(x – 1) + 1 = y * x\) M1A1

so \( * \) is commutative AG

[2 marks]

\(x * (y * z) = x * \left( {(y – 1)(z – 1) + 1} \right)\) M1

\( = (x – 1)\left( {(y – 1)(z – 1) + 1 – 1} \right) + 1\) (A1)

\( = (x – 1)(y – 1)(z – 1) + 1\) A1

\((x * y) * z = \left( {(x – 1)(y – 1) + 1} \right) * z\) M1

\( = \left( {(x – 1)(y – 1) + 1 – 1} \right)(z – 1) + 1\)

\( = (x – 1)(y – 1)(z – 1) + 1\) A1

so \( * \) is associative AG

[5 marks]

\(2 * x = (2 – 1)(x – 1) + 1 = x,{\text{ }}x * 2 = (x – 1)(2 – 1) + 1 = x\) M1

\(2 * x = x * 2 = 2{\text{ }}(2 \in S)\) R1

Note: Accept reference to commutativity instead of explicit expressions.

so 2 is the identity element AG

[2 marks]

\(a * {a^{ – 1}} = 2 \Rightarrow (a – 1)({a^{ – 1}} – 1) + 1 = 2\) M1

so \({a^{ – 1}} = 1 + \frac{1}{{a – 1}}\) A1

since \(a – 1 > 0 \Rightarrow {a^{ – 1}} > 1{\text{ }}({a^{ – 1}} * a = a * {a^{ – 1}})\) R1

Note: R1 dependent on M1.

so each element, \(a \in S\), has an inverse AG

[3 marks]

Examiners report

[N/A]

[N/A]

[N/A]

[N/A]

[N/A]

Question

Consider the set \({S_3} = \{ {\text{ }}p,{\text{ }}q,{\text{ }}r,{\text{ }}s,{\text{ }}t,{\text{ }}u\} \) of permutations of the elements of the set \(\{ 1,{\text{ }}2,{\text{ }}3\} \), defined by

\(p = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 1&2&3 \end{array}} \right),{\text{ }}q = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 1&3&2 \end{array}} \right),{\text{ }}r = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 3&2&1 \end{array}} \right),{\text{ }}s = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 2&1&3 \end{array}} \right),{\text{ }}t = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 2&3&1 \end{array}} \right),{\text{ }}u = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 1&2&3 \\ 3&1&2 \end{array}} \right).\)

Let \( \circ \) denote composition of permutations, so \(a \circ b\) means \(b\) followed by \(a\). You may assume that \(({S_3},{\text{ }} \circ )\) forms a group.

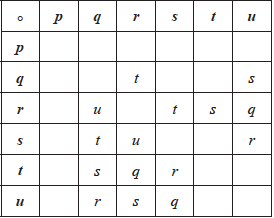

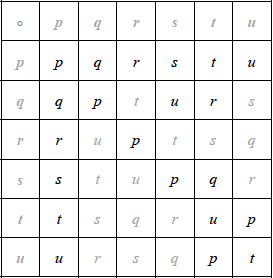

Complete the following Cayley table

[5 marks][4]

(i) State the inverse of each element.

(ii) Determine the order of each element.[6]

Write down the subgroups containing

(i) \(r\),

(ii) \(u\).[2]

▶️Answer/Explanation

Markscheme

(M1)A4

(M1)A4

Note: Award M1 for use of Latin square property and/or attempted multiplication, A1 for the first row or column, A1 for the squares of \(q\), \(r\) and \(s\), then A2 for all correct.

(i) \({p^{ – 1}} = p,{\text{ }}{q^{ – 1}} = q,{\text{ }}{r^{ – 1}} = r,{\text{ }}{s^{ – 1}} = s\) A1

\({t^{ – 1}} = u,{\text{ }}{u^{ – 1}} = t\) A1

Note: Allow FT from part (a) unless the working becomes simpler.

(ii) using the table or direct multiplication (M1)

the orders of \(\{ p,{\text{ }}q,{\text{ }}r,{\text{ }}s,{\text{ }}t,{\text{ }}u\} \) are \(\{ 1,{\text{ }}2,{\text{ }}2,{\text{ }}2,{\text{ }}3,{\text{ }}3\} \) A3

Note: Award A1 for two, three or four correct, A2 for five correct.

[6 marks]

(i) \(\{ p,{\text{ }}r\} {\text{ }}\left( {{\text{and }}({S_3},{\text{ }} \circ )} \right)\) A1

(ii) \(\{ p,{\text{ }}u,{\text{ }}t\} {\text{ }}\left( {{\text{and }}({S_3},{\text{ }} \circ )} \right)\) A1

Note: Award A0A1 if the identity has been omitted.

Award A0 in (i) or (ii) if an extra incorrect “subgroup” has been included.

[2 marks]

Total [13 marks]

Question

\(\{ G,{\text{ }} * \} \) is a group with identity element \(e\). Let \(a,{\text{ }}b \in G\).

a.State Lagrange’s theorem.[2]

b.Verify that the inverse of \(a * {b^{ – 1}}\) is equal to \(b * {a^{ – 1}}\).[3]

Let \(\{ H,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\) be a subgroup of \(\{ G,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\). Let \(R\) be a relation defined on \(G\) by

\[aRb \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H.\]

Prove that \(R\) is an equivalence relation, indicating clearly whenever you are using one of the four properties required of a group.[8]

Let \(\{ H,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\) be a subgroup of \(\{ G,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\) .Let \(R\) be a relation defined on \(G\) by

\[aRb \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H.\]

Show that \(aRb \Leftrightarrow a \in Hb\), where \(Hb\) is the right coset of \(H\) containing \(b\).[3]

Let \(\{ H,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\) be a subgroup of \(\{ G,{\rm{ }} * {\rm{\} }}\) .Let \(R\) be a relation defined on \(G\) by

\[aRb \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H.\]

It is given that the number of elements in any right coset of \(H\) is equal to the order of \(H\).

Explain how this fact together with parts (c) and (d) prove Lagrange’s theorem.[3]

▶️Answer/Explanation

Markscheme

in a finite group the order of any subgroup (exactly) divides the order of the group A1A1

[2 marks]

METHOD 1

\((a * {b^{ – 1}}) * (b * {a^{ – 1}}) = a * {b^{ – 1}} * b * {a^{ – 1}} = a * e * {a^{ – 1}} = a * {a^{ – 1}} = e\) M1A1A1

Note: M1 for multiplying, A1 for at least one of the next 3 expressions,

A1 for \(e\).

Allow \((b * {a^{ – 1}}) * (a * {b^{ – 1}}) = b * {a^{ – 1}} * a * {b^{ – 1}} = b * e * {b^{ – 1}} = b * {b^{ – 1}} = e\).

METHOD 2

\({(a * {b^{ – 1}})^{ – 1}} = {({b^{ – 1}})^{ – 1}} * {a^{ – 1}}\) M1A1

\( = b * {a^{ – 1}}\)A1

[3 marks]

\(a * {a^{ – 1}} = e \in H\;\;\;\)(as \(H\) is a subgroup) M1

so \(aRa\) and hence \(R\) is reflexive

\(aRb \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H\). \(H\) is a subgroup so every element has an inverse in \(H\) so

\({(a * {b^{ – 1}})^{ – 1}} \in H\) R1

\( \Leftrightarrow b * {a^{ – 1}} \in H \Leftrightarrow bRa\) M1

so \(R\) is symmetric

\(aRb,{\text{ }}bRc \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H,{\text{ }}b * {c^{ – 1}} \in H\) M1

as \(H\) is closed \((a * {b^{ – 1}}) * {\text{(}}b * {c^{ – 1}}) \in H\) R1

and using associativity R1

\((a * {b^{ – 1}}) * {\text{(}}b * {c^{ – 1}}) = a * ({b^{ – 1}} * b) * {c^{ – 1}} = a * {c^{ – 1}} \in H \Leftrightarrow aRc\) A1

therefore \(R\) is transitive

\(R\) is reflexive, symmetric and transitive

Note: Can be said separately at the end of each part.

hence it is an equivalence relation AG

[8 marks]

\(aRb \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} \in H \Leftrightarrow a * {b^{ – 1}} = h \in H\) A1

\( \Leftrightarrow a = h * b \Leftrightarrow a \in Hb\) M1R1

[3 marks]

(d) implies that the right cosets of \(H\) are equal to the equivalence classes of the relation in (c) R1

hence the cosets partition \(G\) R1

all the cosets are of the same size as the subgroup \(H\) so the order of \(G\) must be a multiple of \(\left| H \right|\) R1

[3 marks]

Total [19 marks]

Question

Let c be a positive, real constant. Let G be the set \(\{ \left. {x \in \mathbb{R}} \right| – c < x < c\} \) . The binary operation \( * \) is defined on the set G by \(x * y = \frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}}\).

a.Simplify \(\frac{c}{2} * \frac{{3c}}{4}\) .[2]

b.State the identity element for G under \( * \).[1]

c.For \(x \in G\) find an expression for \({x^{ – 1}}\) (the inverse of x under \( * \)).[1]

d.Show that the binary operation \( * \) is commutative on G .[2]

e.Show that the binary operation \( * \) is associative on G .[4]

f. (i) If \(x,{\text{ }}y \in G\) explain why \((c – x)(c – y) > 0\) .

(ii) Hence show that \(x + y < c + \frac{{xy}}{c}\) .[2]

g. Show that G is closed under \( * \).[2]

h. Explain why \(\{ G, * \} \) is an Abelian group.[2]

▶️Answer/Explanation

Markscheme

\(\frac{c}{2} * \frac{{3c}}{4} = \frac{{\frac{c}{2} + \frac{{3c}}{4}}}{{1 + \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4}}}\) M1

\( = \frac{{\frac{{5c}}{4}}}{{\frac{{11}}{8}}} = \frac{{10c}}{{11}}\) A1

[2 marks]

identity is 0 A1

[1 mark]

inverse is –x A1

[1 mark]

\(x * y = \frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}},{\text{ }}y * x = \frac{{y + x}}{{1 + \frac{{yx}}{{{c^2}}}}}\) M1

(since ordinary addition and multiplication are commutative)

\(x * y = y * x{\text{ so }} * \) is commutative R1

Note: Accept arguments using symmetry.

[2 marks]

\((x * y) * z = \frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}} * z = \frac{{\left( {\frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}}} \right) + z}}{{1 + \left( {\frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}}} \right)\frac{z}{{{c^2}}}}}\) M1

\( = \frac{{\frac{{\left( {x + y + z + \frac{{xyz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}}}{{\frac{{\left( {1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}} + \frac{{xz}}{{{c^2}}} + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}}} = \frac{{\left( {x + y + z + \frac{{xyz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \left( {\frac{{xy + xz + yz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)} \right)}}\) A1

\(x * (y * z) = x * \left( {\frac{{y + z}}{{1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}}}} \right) = \frac{{x + \left( {\frac{{y + z}}{{1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}}}} \right)}}{{1 + \frac{x}{{{c^2}}}\left( {\frac{{y + z}}{{1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}}}} \right)}}\)

\( = \frac{{\frac{{\left( {x + \frac{{xyz}}{{{c^2}}} + y + z} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}}}{{\frac{{\left( {1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}} + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}} + \frac{{xz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \frac{{yz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}}} = \frac{{\left( {x + y + z + \frac{{xyz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)}}{{\left( {1 + \left( {\frac{{xy + xz + yz}}{{{c^2}}}} \right)} \right)}}\) A1

since both expressions are the same \( * \) is associative R1

Note: After the initial M1A1, correct arguments using symmetry also gain full marks.

[4 marks]

(i) \(c > x{\text{ and }}c > y \Rightarrow c – x > 0{\text{ and }}c – y > 0 \Rightarrow (c – x)(c – y) > 0\) R1AG

(ii) \({c^2} – cx – cy + xy > 0 \Rightarrow {c^2} + xy > cx + cy \Rightarrow c + \frac{{xy}}{c} > x + y{\text{ (as }}c > 0)\)

so \(x + y < c + \frac{{xy}}{c}\) M1AG

[2 marks]

if \(x,{\text{ }}y \in G{\text{ then }} – c – \frac{{xy}}{c} < x + y < c + \frac{{xy}}{c}\)

thus \( – c\left( {1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}} \right) < x + y < c\left( {1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}} \right){\text{ and }} – c < \frac{{x + y}}{{1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}}}} < c\) M1

\(({\text{as }}1 + \frac{{xy}}{{{c^2}}} > 0){\text{ so }} – c < x * y < c\) A1

proving that G is closed under \( * \) AG

[2 marks]

as \(\{ G, * \} \) is closed, is associative, has an identity and all elements have an inverse R1

it is a group AG

as \( * \) is commutative R1

it is an Abelian group AG

[2 marks]

Examiners report

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.

Most candidates were able to answer part (a) indicating preparation in such questions. Many students failed to identify the command term “state” in parts (b) and (c) and spent a lot of time – usually unsuccessfully – with algebraic methods. Most students were able to offer satisfactory solutions to part (d) and although most showed that they knew what to do in part (e), few were able to complete the proof of associativity. Surprisingly few managed to answer parts (f) and (g) although many who continued to this stage, were able to pick up at least one of the marks for part (h), regardless of what they had done before. Many candidates interpreted the question as asking to prove that the group was Abelian, rather than proving that it was an Abelian group. Few were able to fully appreciate the significance in part (i) although there were a number of reasonable solutions.