CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 24.2 Standard electrode potentials Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 24.2 Standard electrode potentials Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 24.2 Standard electrode potentials Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

define the terms:

(a) standard electrode (reduction) potential

(b) standard cell potentialdescribe the standard hydrogen electrode

describe methods used to measure the standard electrode potentials of:

(a) metals or non-metals in contact with their ions in aqueous solution

(b) ions of the same element in different oxidation statescalculate a standard cell potential by combining two standard electrode potentials

use standard cell potentials to:

(a) deduce the polarity of each electrode and hence explain/deduce the direction of electron flow in

the external circuit of a simple cell

(b) predict the feasibility of a reactiondeduce from E⦵ values the relative reactivity of elements, compounds and ions as oxidising agents or as reducing agents

construct redox equations using the relevant half-equations

predict qualitatively how the value of an electrode potential, E, varies with the concentrations of the aqueous ions

use the Nernst equation, e.g.

E = E⦵ + (0.059/z) log [oxidised species]/[reduced species],

to predict quantitatively how the value of an electrode potential varies with the concentrations of the

aqueous ions; examples include:

Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ ⇌ Cu(s)

Fe³⁺(aq) + e⁻ ⇌ Fe²⁺(aq)understand and use the equation ΔG⦵ = –nE⦵cellF

Standard Electrode and Cell Potentials

Standard electrode potentials are used to compare the tendency of different species to be reduced. These values are then used to calculate the standard cell potential.

(a) Standard Electrode (Reduction) Potential, \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \)

The standard electrode (reduction) potential is defined as the e.m.f. of a half-cell when it is connected to the standard hydrogen electrode, under standard conditions, with all values quoted for reduction.

Standard conditions:

- Temperature of \( \mathrm{298\ K} \)

- Pressure of \( \mathrm{100\ kPa} \)

- Solutions at \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

A more positive value of \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) means a greater tendency for the species to be reduced.

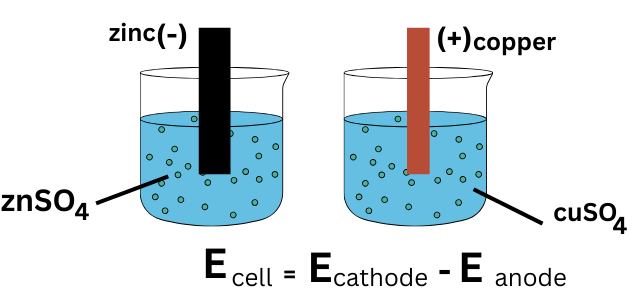

(b) Standard Cell Potential, \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \)

The standard cell potential is defined as the e.m.f. of a complete electrochemical cell under standard conditions.

It is calculated using standard electrode (reduction) potentials:

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = E^\circ_{cathode} – E^\circ_{anode}} \)

A positive value of \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \) indicates a feasible redox reaction.

Example

Explain what is meant by the statement that the standard electrode potential of the \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu} \) half-cell is +0.34 V.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The value is measured relative to the standard hydrogen electrode.

Conditions are standard conditions.

The positive value shows that copper(II) ions are readily reduced to copper metal.

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+}/Zn = -0.76\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu = +0.34\ V} \)

Calculate the standard cell potential and state which electrode is the cathode.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Copper has the more positive standard electrode potential.

Copper is therefore the cathode.

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = 0.34 – (-0.76) = +1.10\ V} \)

The positive cell potential shows the reaction is feasible.

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE)

The standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) is used as the reference electrode against which all standard electrode (reduction) potentials are measured.

Description of the Standard Hydrogen Electrode

The standard hydrogen electrode consists of an inert platinum electrode in contact with hydrogen gas and an acidic solution containing hydrogen ions.

Standard conditions:

- Temperature: \( \mathrm{298\ K} \)

- Pressure of hydrogen gas: \( \mathrm{100\ kPa} \)

- Concentration of hydrogen ions: \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

Hydrogen gas is bubbled over the platinum electrode, which provides a surface for the redox reaction to take place.

The half-equation for the SHE is:

\( \mathrm{2H^+(aq) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons H_2(g)} \)

By convention, the standard electrode potential of the standard hydrogen electrode is defined as 0.00 V.

The SHE can act as either a cathode or an anode, depending on the half-cell it is connected to.

Example

State two features of the standard hydrogen electrode.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Hydrogen gas is supplied at a pressure of \( \mathrm{100\ kPa} \).

The hydrogen ion concentration is \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

Example

Explain why platinum is used as the electrode in the standard hydrogen electrode.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Platinum is chemically inert.

It does not react with hydrogen or hydrogen ions.

It provides a surface for electron transfer between hydrogen gas and hydrogen ions.

Measuring Standard Electrode Potentials

Standard electrode potentials are measured by constructing an electrochemical cell that includes the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) and the half-cell of interest. All measurements are carried out under standard conditions.

Standard Conditions

- Temperature: \( \mathrm{298\ K} \)

- Pressure: \( \mathrm{100\ kPa} \)

- Solutions: \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

(a) Metals or Non-metals in Contact with Their Ions

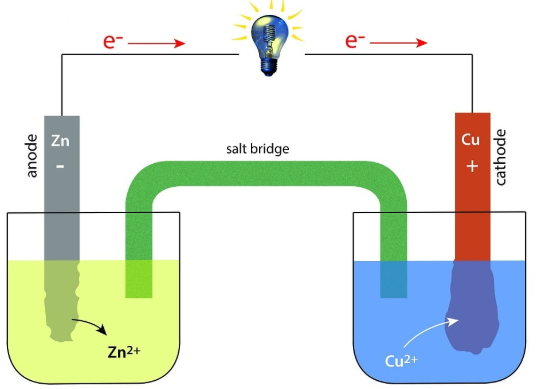

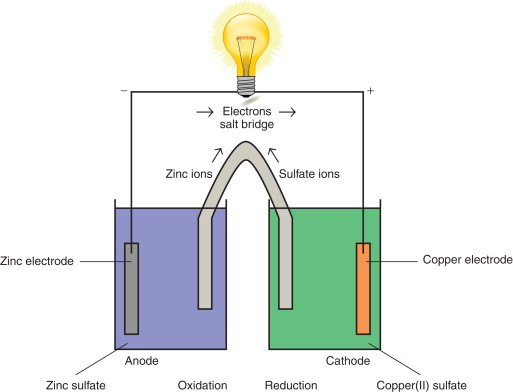

A standard electrode potential for a metal (or non-metal) is measured by connecting its half-cell to the standard hydrogen electrode.

For a metal:

A strip of the metal is placed in a solution containing its ions at \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

For a non-metal:

An inert platinum electrode is used to provide a conducting surface.

The two half-cells are connected by:

- a salt bridge to complete the circuit

- a high-resistance voltmeter to measure the e.m.f.

The measured e.m.f. is the standard electrode potential, since the SHE has \( \mathrm{E^\circ = 0.00\ V} \).

(b) Ions of the Same Element in Different Oxidation States

To measure the standard electrode potential of ions of the same element in different oxidation states, an inert platinum electrode is used.

The platinum electrode is placed in a solution containing both ions at \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

This half-cell is connected to the standard hydrogen electrode and the e.m.f. is measured.

Platinum does not react but allows electron transfer between the ions.

Example

Describe how the standard electrode potential of the \( \mathrm{Zn^{2+}/Zn} \) half-cell is measured.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A zinc electrode is placed in a \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) solution of zinc ions.

The half-cell is connected to the standard hydrogen electrode.

A salt bridge and voltmeter are used.

The measured e.m.f. gives the standard electrode potential.

Example

Describe how the standard electrode potential of the \( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \) half-cell is measured.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A platinum electrode is placed in a solution containing \( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}} \) and \( \mathrm{Fe^{2+}} \) ions, each at \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

The half-cell is connected to the standard hydrogen electrode.

A salt bridge and voltmeter are used.

The measured e.m.f. gives the standard electrode potential.

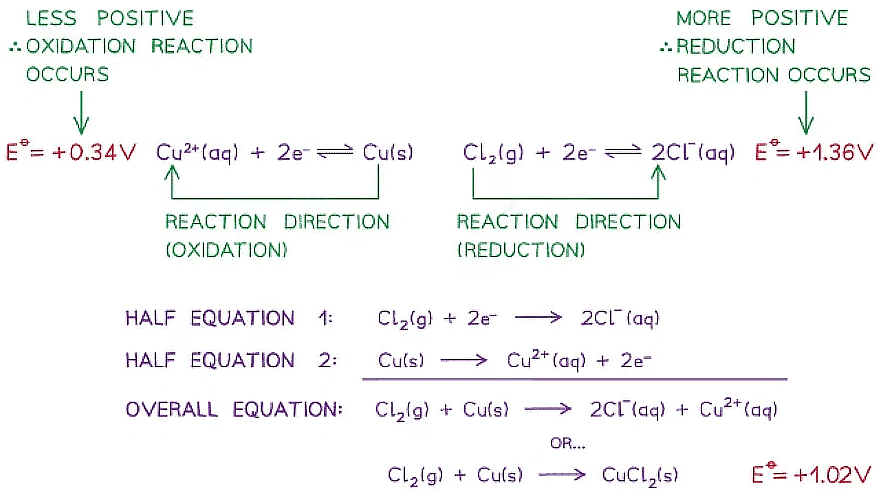

Calculating the Standard Cell Potential

The standard cell potential, \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \), can be calculated by combining two standard electrode (reduction) potentials. This allows prediction of the feasibility of a redox reaction.

Key Rule

All standard electrode potentials are quoted as reduction potentials.

Method

- Identify the two half-cells involved

- Determine which half-cell has the more positive reduction potential

- The half-cell with the more positive \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) is the cathode

- The half-cell with the less positive \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) is the anode

- Calculate the cell potential using the equation below

Equation

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = E^\circ_{cathode} – E^\circ_{anode}} \)

A positive value of \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \) indicates a feasible reaction.

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+}/Zn = -0.76\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu = +0.34\ V} \)

Calculate the standard cell potential.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The copper half-cell has the more positive reduction potential.

Copper is the cathode and zinc is the anode.

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = 0.34 – (-0.76)} \)

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = +1.10\ V} \)

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+} = +0.77\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{I_2/I^- = +0.54\ V} \)

Calculate the standard cell potential and identify the overall redox reaction.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \) has the more positive reduction potential.

It acts as the cathode.

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = 0.77 – 0.54 = +0.23\ V} \)

Reduction at cathode:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+} + e^- \rightarrow Fe^{2+}} \)

Oxidation at anode:

\( \mathrm{2I^- \rightarrow I_2 + 2e^-} \)

The positive cell potential shows the reaction is feasible.

Using Standard Cell Potentials

Standard cell potentials, \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \), are used to determine electrode polarity, the direction of electron flow, and the feasibility of redox reactions.

Key Principles

- All standard electrode potentials are quoted as reduction potentials

- The half-cell with the more positive \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) is reduced

- Reduction occurs at the cathode

- Oxidation occurs at the anode

(a) Polarity of Electrodes and Direction of Electron Flow

In a simple (galvanic) cell:

- The cathode is positive

- The anode is negative

- Electrons flow in the external circuit from the anode to the cathode

Electrons always flow from the half-cell with the less positive standard electrode potential to the half-cell with the more positive standard electrode potential.

(b) Predicting Feasibility Using \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \)

The standard cell potential is calculated using:

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = E^\circ_{cathode} – E^\circ_{anode}} \)

- If \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} > 0} \), the reaction is feasible

- If \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} < 0} \), the reaction is not feasible

A positive cell potential corresponds to a negative Gibbs free energy change.

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+}/Zn = -0.76\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu = +0.34\ V} \)

Deduce the polarity of each electrode and the direction of electron flow.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Copper has the more positive standard electrode potential.

Copper is the cathode and is positive.

Zinc is the anode and is negative.

Electrons flow from zinc to copper in the external circuit.

Example

Using standard electrode potentials, determine whether the following reaction is feasible:

\( \mathrm{2Fe^{3+}(aq) + 2I^-(aq) \rightarrow 2Fe^{2+}(aq) + I_2(aq)} \)

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+} = +0.77\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{I_2/I^- = +0.54\ V} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \) has the more positive reduction potential.

Iron(III) ions are reduced at the cathode.

Iodide ions are oxidised at the anode.

\( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = 0.77 – 0.54 = +0.23\ V} \)

The positive cell potential shows the reaction is feasible.

Deducing Oxidising and Reducing Strength from Standard Electrode Potentials

Standard electrode (reduction) potentials, \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \), can be used to compare the relative reactivity of elements, compounds and ions as oxidising agents or reducing agents.

Key Principle

All standard electrode potentials are quoted as reduction potentials.

Oxidising Agents

An oxidising agent gains electrons and is itself reduced.

Species with a more positive standard electrode potential are stronger oxidising agents.

This is because they have a greater tendency to accept electrons.

Reducing Agents

A reducing agent loses electrons and is itself oxidised.

Species with a more negative standard electrode potential are stronger reducing agents.

This is because they have a greater tendency to donate electrons.

Important Exam Rules

- More positive \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) → stronger oxidising agent

- More negative \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) → stronger reducing agent

- Electrons flow from lower to higher \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) values

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Ag^+/Ag = +0.80\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu = +0.34\ V} \)

Deduce which ion is the stronger oxidising agent.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Silver ions have the more positive standard electrode potential.

\( \mathrm{Ag^+} \) therefore has a greater tendency to gain electrons.

\( \mathrm{Ag^+} \) is the stronger oxidising agent.

Example

The standard electrode potentials are:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+}/Zn = -0.76\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Fe^{2+}/Fe = -0.44\ V} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu = +0.34\ V} \)

Deduce the relative strength of zinc, iron and copper as reducing agents.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Zinc has the most negative standard electrode potential.

Zinc has the greatest tendency to lose electrons.

Zinc is the strongest reducing agent.

Iron is a weaker reducing agent than zinc but stronger than copper.

Copper, with the most positive value, is the weakest reducing agent.

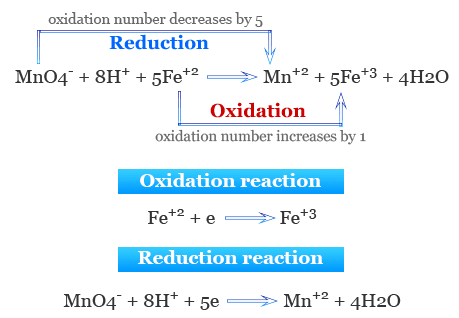

Constructing Redox Equations from Half-Equations

Redox equations are constructed by combining appropriate oxidation and reduction half-equations. Electrons must always be conserved.

Key Definitions

- Oxidation: loss of electrons

- Reduction: gain of electrons

General Method

- Write the two relevant half-equations

- Identify which half-equation is oxidation and which is reduction

- Multiply one or both half-equations so the number of electrons is the same

- Add the half-equations together

- Cancel electrons that appear on both sides

Electrons must never appear in the final overall equation.

Example

Construct the overall redox equation from the following half-equations:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+} + 2e^- \rightarrow Zn} \)

\( \mathrm{Cu \rightarrow Cu^{2+} + 2e^-} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Both half-equations involve two electrons.

Add the equations together and cancel electrons:

\( \mathrm{Zn^{2+} + Cu \rightarrow Zn + Cu^{2+}} \)

Example

Construct the overall redox equation from the following half-equations:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+} + e^- \rightarrow Fe^{2+}} \)

\( \mathrm{2I^- \rightarrow I_2 + 2e^-} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The iron half-equation involves one electron.

The iodide half-equation involves two electrons.

Multiply the iron half-equation by two:

\( \mathrm{2Fe^{3+} + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Fe^{2+}} \)

Add the half-equations and cancel electrons:

\( \mathrm{2Fe^{3+} + 2I^- \rightarrow 2Fe^{2+} + I_2} \)

Effect of Ion Concentration on Electrode Potential

The value of an electrode potential, \( \mathrm{E} \), depends on the concentrations of the aqueous ions involved in the half-equation. Changes in concentration affect the position of equilibrium of the redox process.

General Principle

An electrode potential becomes more positive if the conditions favour reduction, and more negative if they favour oxidation.

Reduction Half-Equations

For a typical reduction half-equation:

\( \mathrm{M^{n+}(aq) + ne^- \rightleftharpoons M(s)} \)

- Increasing the concentration of \( \mathrm{M^{n+}} \) makes \( \mathrm{E} \) more positive

- Decreasing the concentration of \( \mathrm{M^{n+}} \) makes \( \mathrm{E} \) more negative

This is because increasing ion concentration increases the tendency for ions to gain electrons.

Redox Systems with Ions Only

For half-cells containing ions in different oxidation states:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Fe^{2+}(aq)} \)

- Increasing \( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}} \) concentration makes \( \mathrm{E} \) more positive

- Increasing \( \mathrm{Fe^{2+}} \) concentration makes \( \mathrm{E} \) more negative

Electrode potential depends on the ratio of oxidised to reduced species.

Standard Conditions Reminder

Standard electrode potentials, \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \), are measured at \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \). Any change in concentration causes the electrode potential to deviate from the standard value.

Example

Explain qualitatively how increasing the concentration of \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}(aq)} \) affects the electrode potential of the \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu} \) half-cell.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Increasing the concentration of \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}} \) favours reduction.

The tendency to gain electrons increases.

The electrode potential becomes more positive.

Example

The half-equation is:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Fe^{2+}(aq)} \)

Explain how the electrode potential changes if the concentration of \( \mathrm{Fe^{2+}} \) increases.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Increasing \( \mathrm{Fe^{2+}} \) shifts the equilibrium towards oxidation.

The tendency for reduction decreases.

The electrode potential becomes less positive (more negative).

Using the Nernst Equation

The Nernst equation allows the electrode potential, \( \mathrm{E} \), to be calculated under non-standard conditions, when aqueous ion concentrations are not \( \mathrm{1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

Nernst Equation (at 298 K)

\( \mathrm{E = E^\circ + \dfrac{0.059}{z} \log \dfrac{[\text{oxidised species}]}{[\text{reduced species}]} } \)

Where:

- \( \mathrm{E} \) is the electrode potential under non-standard conditions (V)

- \( \mathrm{E^\circ} \) is the standard electrode potential (V)

- \( \mathrm{z} \) is the number of electrons transferred

- Concentrations are in \( \mathrm{mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

Pure solids and liquids are omitted from the expression.

Example: \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu} \) Half-Cell

Half-equation:

\( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}(aq) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons Cu(s)} \)

Here, \( \mathrm{z = 2} \) and solid copper is omitted:

\( \mathrm{E = E^\circ + \dfrac{0.059}{2} \log[Cu^{2+}]} \)

Example : \( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \) Half-Cell

Half-equation:

\( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Fe^{2+}(aq)} \)

Here, \( \mathrm{z = 1} \):

\( \mathrm{E = E^\circ + 0.059 \log \dfrac{[Fe^{3+}]}{[Fe^{2+}]} } \)

Example

The standard electrode potential for \( \mathrm{Cu^{2+}/Cu} \) is +0.34 V. Calculate the electrode potential when \( \mathrm{[Cu^{2+}] = 0.010\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Substitute into the Nernst equation:

\( \mathrm{E = 0.34 + \dfrac{0.059}{2} \log(0.010)} \)

\( \mathrm{\log(0.010) = -2} \)

\( \mathrm{E = 0.34 + (0.0295 \times -2)} \)

\( \mathrm{E = 0.34 – 0.059 = 0.281\ V} \)

The electrode potential decreases as the ion concentration decreases.

Example

The standard electrode potential for \( \mathrm{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \) is +0.77 V. Calculate the electrode potential when:

\( \mathrm{[Fe^{3+}] = 0.20\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

\( \mathrm{[Fe^{2+}] = 1.0\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Substitute into the Nernst equation:

\( \mathrm{E = 0.77 + 0.059 \log \left(\dfrac{0.20}{1.0}\right)} \)

\( \mathrm{\log(0.20) = -0.699} \)

\( \mathrm{E = 0.77 + (0.059 \times -0.699)} \)

\( \mathrm{E = 0.77 – 0.041 = 0.729\ V} \)

The electrode potential becomes less positive when the ratio \( \mathrm{[Fe^{3+}]/[Fe^{2+}]} \) decreases.

Relationship Between Gibbs Free Energy and Cell Potential

The feasibility of a redox reaction can be related directly to its standard cell potential using the Gibbs free energy equation.

The Equation

The relationship between Gibbs free energy and cell potential is:

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -nF E^\circ_{cell}} \)

Where:

- \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ} \) is the standard Gibbs free energy change (J mol⁻¹)

- \( \mathrm{n} \) is the number of moles of electrons transferred

- \( \mathrm{F} \) is the Faraday constant (\( \mathrm{9.65 \times 10^4\ C\,mol^{-1}} \))

- \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell}} \) is the standard cell potential (V)

If required, \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ} \) can be converted from J mol⁻¹ to kJ mol⁻¹ by dividing by 1000.

Key Interpretations

- If \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} > 0} \), then \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ < 0} \) → reaction is feasible

- If \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} < 0} \), then \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ > 0} \) → reaction is not feasible

- If \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = 0} \), then \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = 0} \) → system at equilibrium

This equation links electrode potentials directly to chemical feasibility.

Example

A cell has a standard cell potential of \( \mathrm{+1.10\ V} \). Two moles of electrons are transferred. Calculate \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the equation:

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -nF E^\circ_{cell}} \)

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -2 \times 9.65 \times 10^4 \times 1.10} \)

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -2.12 \times 10^5\ J\,mol^{-1}} \)

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -212\ kJ\,mol^{-1}} \)

The reaction is feasible.

Example

The reaction:

\( \mathrm{2Fe^{3+}(aq) + 2I^-(aq) \rightarrow 2Fe^{2+}(aq) + I_2(aq)} \)

has \( \mathrm{E^\circ_{cell} = +0.23\ V} \). Calculate \( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ} \) and comment on feasibility.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Two electrons are transferred, so \( \mathrm{n = 2} \).

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -2 \times 9.65 \times 10^4 \times 0.23} \)

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -4.44 \times 10^4\ J\,mol^{-1}} \)

\( \mathrm{\Delta G^\circ = -44.4\ kJ\,mol^{-1}} \)

The negative value shows the reaction is feasible.