CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 25.1 Acids and bases Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 25.1 Acids and bases Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 25.1 Acids and bases Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

understand and use the terms conjugate acid and conjugate base

define conjugate acid–base pairs, identifying such pairs in reactions

define mathematically the terms pH, Kₐ, pKₐ and Kᵥ and use them in calculations

(Kᵦ and the equation Kᵥ = Kₐ × Kᵦ will not be tested)calculate [H⁺(aq)] and pH values for:

(a) strong acids

(b) strong alkalis

(c) weak acids(a) define a buffer solution

(b) explain how a buffer solution can be made

(c) explain how buffer solutions control pH; use chemical equations in these explanations

(d) describe and explain the uses of buffer solutions, including the role of HCO₃⁻ in controlling pH in

bloodcalculate the pH of buffer solutions, given appropriate data

understand and use the term solubility product, Kₛₚ

write an expression for Kₛₚ

calculate Kₛₚ from concentrations and vice versa

(a) understand and use the common ion effect to explain the different solubility of a compound in a solution containing a common ion

(b) perform calculations using Kₛₚ values and concentration of a common ion

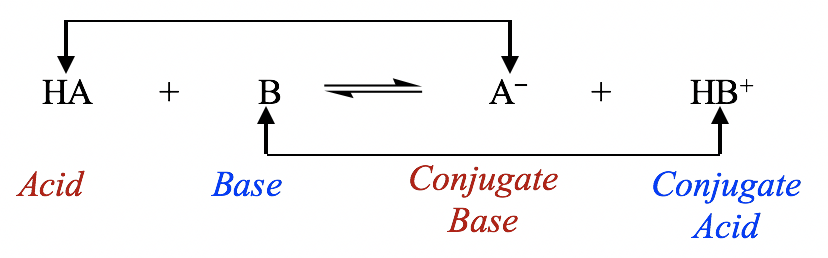

Conjugate Acids and Conjugate Bases

Brønsted–Lowry acid–base reactions involve the transfer of protons. The terms conjugate acid and conjugate base are used to describe species related by the loss or gain of a proton.

Definitions

A conjugate acid is the species formed when a base gains a proton.

A conjugate base is the species formed when an acid loses a proton.

An acid–base pair that differs by one proton is called a conjugate acid–base pair.

General Representation

For an acid:

\( \mathrm{HA \rightleftharpoons H^+ + A^-} \)

• \( \mathrm{HA} \) is the acid • \( \mathrm{A^-} \) is its conjugate base

For a base:

\( \mathrm{B + H^+ \rightleftharpoons BH^+} \)

• \( \mathrm{B} \) is the base • \( \mathrm{BH^+} \) is its conjugate acid

Example

Identify the conjugate acid–base pairs in the reaction:

\( \mathrm{NH_3(aq) + H_2O(l) \rightleftharpoons NH_4^+(aq) + OH^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{NH_3} \) is a base and gains a proton to form \( \mathrm{NH_4^+} \).

\( \mathrm{NH_4^+} \) is the conjugate acid of ammonia.

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) is an acid and loses a proton to form \( \mathrm{OH^-} \).

\( \mathrm{OH^-} \) is the conjugate base of water.

Example

For the reaction:

\( \mathrm{HSO_4^-(aq) + H_2O(l) \rightleftharpoons SO_4^{2-}(aq) + H_3O^+(aq)} \)

Identify the acid, base, conjugate acid and conjugate base.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{HSO_4^-} \) donates a proton and acts as the acid.

\( \mathrm{SO_4^{2-}} \) is its conjugate base.

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) accepts a proton and acts as the base.

\( \mathrm{H_3O^+} \) is the conjugate acid of water.

Conjugate Acid–Base Pairs

In Brønsted–Lowry acid–base chemistry, acids and bases are related to each other by the transfer of a proton. These related species are described as conjugate acid–base pairs.

Definition

A conjugate acid–base pair consists of two species that differ by one proton (H⁺).

• The acid loses a proton to form its conjugate base

• The base gains a proton to form its conjugate acid

General Representation

For an acid:

\( \mathrm{HA \rightleftharpoons H^+ + A^-} \)

\( \mathrm{HA} \) and \( \mathrm{A^-} \) form a conjugate acid–base pair.

For a base:

\( \mathrm{B + H^+ \rightleftharpoons BH^+} \)

\( \mathrm{B} \) and \( \mathrm{BH^+} \) form a conjugate acid–base pair.

Identifying Conjugate Acid–Base Pairs in Reactions

- Find the species that loses a proton (the acid)

- Find the species that gains a proton (the base)

- Match each species with the form that differs by one H⁺

Example

Identify the conjugate acid–base pairs in the reaction:

\( \mathrm{HCl(aq) + H_2O(l) \rightarrow Cl^-(aq) + H_3O^+(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{HCl} \) donates a proton and acts as the acid.

\( \mathrm{Cl^-} \) is the conjugate base of \( \mathrm{HCl} \).

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) accepts a proton and acts as the base.

\( \mathrm{H_3O^+} \) is the conjugate acid of \( \mathrm{H_2O} \).

Conjugate pairs: \( \mathrm{HCl/Cl^-} \) and \( \mathrm{H_2O/H_3O^+} \).

Example

Identify all conjugate acid–base pairs in the reaction:

\( \mathrm{NH_4^+(aq) + OH^-(aq) \rightleftharpoons NH_3(aq) + H_2O(l)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{NH_4^+} \) donates a proton and is the acid.

\( \mathrm{NH_3} \) is its conjugate base.

\( \mathrm{OH^-} \) accepts a proton and is the base.

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) is the conjugate acid of \( \mathrm{OH^-} \).

Conjugate pairs: \( \mathrm{NH_4^+/NH_3} \) and \( \mathrm{OH^-/H_2O} \).

pH and Acid–Base Equilibrium Constants

The strength of acids and the acidity of solutions are described quantitatively using pH, acid dissociation constants, and the ionic product of water.

(a) pH

![]()

pH is defined mathematically as:

\( \mathrm{pH = -\log[H^+]} \)

where \( \mathrm{[H^+]} \) is the hydrogen ion concentration in \( \mathrm{mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

This equation can be rearranged to calculate hydrogen ion concentration:

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = 10^{-pH}} \)

(b) Acid Dissociation Constant, \( \mathrm{K_a} \)

For a weak acid:

\( \mathrm{HA(aq) + H_2O(l) \rightleftharpoons H_3O^+(aq) + A^-(aq)} \)

The acid dissociation constant is defined as:

\( \mathrm{K_a = \dfrac{[H^+][A^-]}{[HA]}} \)

A larger value of \( \mathrm{K_a} \) indicates a stronger acid.

(c) \( \mathrm{pK_a} \)

The term \( \mathrm{pK_a} \) is defined mathematically as:

\( \mathrm{pK_a = -\log K_a} \)

A smaller value of \( \mathrm{pK_a} \) corresponds to a stronger acid.

(d) Ionic Product of Water, \( \mathrm{K_w} \)![]()

The ionic product of water is defined as:

\( \mathrm{K_w = [H^+][OH^-]} \)

At \( \mathrm{298\ K} \):

\( \mathrm{K_w = 1.0 \times 10^{-14}} \)

Example

Calculate the pH of a solution with \( \mathrm{[H^+] = 2.5 \times 10^{-3}\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the definition of pH:

\( \mathrm{pH = -\log(2.5 \times 10^{-3})} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = 2.60} \)

Example

A weak acid has a \( \mathrm{K_a} \) value of \( \mathrm{1.8 \times 10^{-5}} \). Calculate its \( \mathrm{pK_a} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the definition of \( \mathrm{pK_a} \):

\( \mathrm{pK_a = -\log(1.8 \times 10^{-5})} \)

\( \mathrm{pK_a = 4.74} \)

This value indicates a weak acid.

Calculating pH and \( \mathrm{[H^+]} \) Values

The method used to calculate hydrogen ion concentration and pH depends on whether the acid or alkali is strong or weak.

Key Equations

\( \mathrm{pH = -\log[H^+]} \)

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = 10^{-pH}} \)

(a) Strong Acids

Strong acids are assumed to be fully dissociated in aqueous solution.

For a monoprotic strong acid:

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = \text{acid concentration}} \)

(b) Strong Alkalis

Strong alkalis are assumed to be fully dissociated in aqueous solution.

First calculate \( \mathrm{[OH^-]} \), then use \( \mathrm{K_w} \):

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = \dfrac{K_w}{[OH^-]}} \)

(c) Weak Acids

Weak acids are partially dissociated. Their hydrogen ion concentration is calculated using \( \mathrm{K_a} \).

For a weak acid \( \mathrm{HA} \):

\( \mathrm{K_a = \dfrac{[H^+][A^-]}{[HA]}} \)

An ICE table or approximation is usually used.

Example

Calculate the pH of:

(i) \( \mathrm{0.020\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) hydrochloric acid

(ii) \( \mathrm{0.010\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) sodium hydroxide

▶️ Answer / Explanation

(i) HCl is a strong acid and fully dissociated.

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = 0.020} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = -\log(0.020) = 1.70} \)

(ii) NaOH is a strong alkali and fully dissociated.

\( \mathrm{[OH^-] = 0.010} \)

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = \dfrac{1.0 \times 10^{-14}}{0.010} = 1.0 \times 10^{-12}} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = 12.0} \)

Example

A weak acid, HA, has a \( \mathrm{K_a} \) value of \( \mathrm{1.8 \times 10^{-5}} \). Calculate the pH of a \( \mathrm{0.100\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) solution of HA.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Let the concentration of dissociated acid be \( \mathrm{x} \).

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = x,\ [A^-] = x,\ [HA] = 0.100 – x} \)

Substitute into the \( \mathrm{K_a} \) expression:

\( \mathrm{1.8 \times 10^{-5} = \dfrac{x^2}{0.100}} \)

\( \mathrm{x^2 = 1.8 \times 10^{-6}} \)

\( \mathrm{x = 1.34 \times 10^{-3}} \)

\( \mathrm{[H^+] = 1.34 \times 10^{-3}} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = -\log(1.34 \times 10^{-3}) = 2.87} \)

Buffer Solutions

Buffer solutions are essential in chemistry and biology because they resist changes in pH when small amounts of acid or alkali are added.

(a) Definition of a Buffer Solution

A buffer solution is a solution that resists changes in pH when small amounts of acid or alkali are added.

(b) Preparation of a Buffer Solution![]()

A buffer solution is made by mixing:

- a weak acid and its conjugate base (usually as a salt)

- or a weak base and its conjugate acid

Examples:

- Ethanoic acid and sodium ethanoate

- Ammonia solution and ammonium chloride

(c) How Buffer Solutions Control pH

Buffer action depends on the presence of large concentrations of a weak acid and its conjugate base.

Consider an acidic buffer made from ethanoic acid and ethanoate ions:

\( \mathrm{CH_3COOH(aq) \rightleftharpoons H^+(aq) + CH_3COO^-(aq)} \)

Response to added acid![]()

Added hydrogen ions are removed by reaction with the conjugate base:

\( \mathrm{H^+(aq) + CH_3COO^-(aq) \rightarrow CH_3COOH(aq)} \)

Response to added alkali

Added hydroxide ions react with the weak acid:

\( \mathrm{OH^-(aq) + CH_3COOH(aq) \rightarrow CH_3COO^-(aq) + H_2O(l)} \)

In both cases, the pH changes only slightly.

(d) Uses of Buffer Solutions

Buffer solutions are used:

- to maintain constant pH in biological systems

- in enzymatic reactions, where pH affects enzyme activity

- in industrial processes and laboratory solutions

The bicarbonate buffer system in blood

Blood pH is maintained at about 7.4 by the hydrogencarbonate (bicarbonate) buffer system.

\( \mathrm{CO_2(aq) + H_2O(l) \rightleftharpoons H_2CO_3(aq)} \)

\( \mathrm{H_2CO_3(aq) \rightleftharpoons H^+(aq) + HCO_3^-(aq)} \)

• Added \( \mathrm{H^+} \) is removed by \( \mathrm{HCO_3^-} \)

• Added \( \mathrm{OH^-} \) reacts with \( \mathrm{H_2CO_3} \)

This system prevents dangerous changes in blood pH.

Example

Explain how a buffer made from ethanoic acid and sodium ethanoate resists an increase in pH when sodium hydroxide is added.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The hydroxide ions react with ethanoic acid.

\( \mathrm{OH^- + CH_3COOH \rightarrow CH_3COO^- + H_2O} \)

The added OH⁻ is removed, so the pH increases only slightly.

Example

Explain how the hydrogencarbonate buffer system controls the pH of blood when excess hydrogen ions are produced during exercise.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Hydrogen ions combine with hydrogencarbonate ions.

\( \mathrm{H^+ + HCO_3^- \rightarrow H_2CO_3} \)

Carbonic acid can then decompose to carbon dioxide and water.

This prevents a large decrease in blood pH.

Calculating the pH of Buffer Solutions

The pH of a buffer solution can be calculated using the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation, provided the concentrations of the weak acid and its conjugate base (or vice versa) are known.

The Henderson–Hasselbalch Equation

For an acidic buffer:

\( \mathrm{pH = pK_a + \log \dfrac{[\text{conjugate base}]}{[\text{acid}]} } \)

This equation is derived from the \( \mathrm{K_a} \) expression and assumes that the concentrations of acid and conjugate base change very little.

Important Notes

- Concentrations must be in the same units

- pH depends on the ratio of base to acid, not their absolute values

- If concentrations are equal, then \( \mathrm{pH = pK_a} \)

Example

A buffer solution is made by mixing \( \mathrm{0.20\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) ethanoic acid and \( \mathrm{0.20\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) sodium ethanoate. The \( \mathrm{pK_a} \) of ethanoic acid is 4.76. Calculate the pH of the buffer.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation:

\( \mathrm{pH = 4.76 + \log \dfrac{0.20}{0.20}} \)

\( \mathrm{\log(1) = 0} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = 4.76} \)

The pH equals the pKa because the concentrations are equal.

Example

A buffer solution contains \( \mathrm{0.150\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) ethanoic acid and \( \mathrm{0.050\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) sodium ethanoate. The \( \mathrm{K_a} \) of ethanoic acid is \( \mathrm{1.8 \times 10^{-5}} \). Calculate the pH of the buffer.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

First calculate \( \mathrm{pK_a} \):

\( \mathrm{pK_a = -\log(1.8 \times 10^{-5}) = 4.74} \)

Apply the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation:

\( \mathrm{pH = 4.74 + \log \dfrac{0.050}{0.150}} \)

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{0.050}{0.150} = 0.333} \)

\( \mathrm{\log(0.333) = -0.477} \)

\( \mathrm{pH = 4.74 – 0.48 = 4.26} \)

The pH is lower than the pKa because the acid concentration is greater.

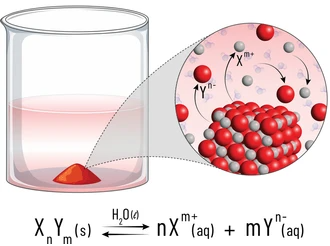

Solubility Product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \)

The solubility product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \), is used to describe the extent to which a sparingly soluble ionic compound dissolves in water.

Definition of the Solubility Product

The solubility product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \), is the equilibrium constant for the dissolution of a sparingly soluble salt, expressed in terms of the concentrations of the ions in solution.

Only aqueous ions appear in the expression. Solid substances are omitted.

General Expression

For a salt \( \mathrm{A_{x}B_{y}(s)} \):

\( \mathrm{A_{x}B_{y}(s) \rightleftharpoons xA^{y+}(aq) + yB^{x-}(aq)} \)

The solubility product is:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [A^{y+}]^x [B^{x-}]^y} \)

A smaller value of \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) indicates a less soluble salt.

Important Exam Rules

- \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) applies only to saturated solutions

- Units are not normally required

- \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) is constant at a given temperature

Example

Write the \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) expression for silver chloride.

\( \mathrm{AgCl(s) \rightleftharpoons Ag^+(aq) + Cl^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Ag^+][Cl^-]} \)

Example

The solubility product of calcium fluoride is \( \mathrm{K_{sp} = 3.9 \times 10^{-11}} \). Write an expression for \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) and explain why calcium fluoride is only sparingly soluble.

\( \mathrm{CaF_2(s) \rightleftharpoons Ca^{2+}(aq) + 2F^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The solubility product expression is:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Ca^{2+}][F^-]^2} \)

The very small value of \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) shows that only a small concentration of ions is present at equilibrium.

This indicates that calcium fluoride is sparingly soluble.

Writing an Expression for the Solubility Product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \)

![]()

The solubility product expression shows the relationship between the concentrations of ions in a saturated solution of a sparingly soluble salt.

General Rules

- Write the equilibrium equation for dissolution

- Include only aqueous ions in the expression

- Exclude solids completely

- Raise each concentration to the power of its stoichiometric coefficient

General Form

For a salt \( \mathrm{A_{x}B_{y}(s)} \):

\( \mathrm{A_{x}B_{y}(s) \rightleftharpoons xA^{y+}(aq) + yB^{x-}(aq)} \)

The solubility product expression is:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [A^{y+}]^x [B^{x-}]^y} \)

The value of \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) applies only to a saturated solution at a fixed temperature.

Example

Write the solubility product expression for lead(II) chloride.

\( \mathrm{PbCl_2(s) \rightleftharpoons Pb^{2+}(aq) + 2Cl^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Pb^{2+}][Cl^-]^2} \)

Example

Write the solubility product expression for aluminium hydroxide.

\( \mathrm{Al(OH)_3(s) \rightleftharpoons Al^{3+}(aq) + 3OH^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Al^{3+}][OH^-]^3} \)

The solid aluminium hydroxide does not appear in the expression.

Calculating \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) and Solubility

The solubility product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \), can be calculated from equilibrium ion concentrations. Conversely, if \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) is known, it can be used to calculate ion concentrations or the molar solubility of a salt.

General Method

- Write the balanced dissolution equation

- Write the correct \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) expression

- Substitute known concentrations, or represent them using a variable

- Solve for the unknown quantity

Example Framework

For a salt \( \mathrm{MX(s)} \):

\( \mathrm{MX(s) \rightleftharpoons M^+(aq) + X^-(aq)} \)

If the molar solubility is \( \mathrm{s} \):

\( \mathrm{[M^+] = s,\ [X^-] = s} \)

So:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = s^2} \)

Unequal Stoichiometry Example

For \( \mathrm{MX_2(s)} \):

\( \mathrm{MX_2(s) \rightleftharpoons M^{2+}(aq) + 2X^-(aq)} \)

If solubility is \( \mathrm{s} \):

\( \mathrm{[M^{2+}] = s,\ [X^-] = 2s} \)

So:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = s(2s)^2 = 4s^3} \)

Example

A saturated solution of silver chloride contains \( \mathrm{[Ag^+] = 1.3 \times 10^{-5}\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \). Calculate \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) for silver chloride.

\( \mathrm{AgCl(s) \rightleftharpoons Ag^+(aq) + Cl^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

From stoichiometry:

\( \mathrm{[Cl^-] = 1.3 \times 10^{-5}} \)

Write the expression:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Ag^+][Cl^-]} \)

Substitute values:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = (1.3 \times 10^{-5})^2} \)

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = 1.69 \times 10^{-10}} \)

Example

The solubility product of calcium hydroxide is \( \mathrm{K_{sp} = 5.5 \times 10^{-6}} \). Calculate the concentration of hydroxide ions in a saturated solution.

\( \mathrm{Ca(OH)_2(s) \rightleftharpoons Ca^{2+}(aq) + 2OH^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Let the molar solubility be \( \mathrm{s} \).

\( \mathrm{[Ca^{2+}] = s,\ [OH^-] = 2s} \)

Write the \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) expression:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = s(2s)^2 = 4s^3} \)

Solve for \( \mathrm{s} \):

\( \mathrm{s^3 = \dfrac{5.5 \times 10^{-6}}{4}} \)

\( \mathrm{s = 0.011} \)

Calculate hydroxide ion concentration:

\( \mathrm{[OH^-] = 2s = 2 \times 0.011 = 0.022\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

The Common Ion Effect

The common ion effect explains how the solubility of a sparingly soluble salt changes when one of its ions is already present in solution. This effect is interpreted using Le Chatelier’s principle and the solubility product, \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \).

(a) Explaining the Common Ion Effect

The common ion effect is the reduction in solubility of an ionic compound when a solution already contains one of the ions produced on dissolution.

![]()

For a salt \( \mathrm{MX(s)} \):

\( \mathrm{MX(s) \rightleftharpoons M^+(aq) + X^-(aq)} \)

If extra \( \mathrm{X^-} \) ions are added from another source (e.g. a soluble salt), the equilibrium shifts to the left to oppose the increase in ion concentration.

As a result, less solid dissolves and the solubility decreases.

(b) Using \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) with a Common Ion

The value of \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) remains constant at a fixed temperature. When a common ion is present, the concentration of the other ion must decrease to maintain the same \( \mathrm{K_{sp}} \) value.

This allows calculation of solubility in the presence of a common ion.

Example

Silver chloride is less soluble in sodium chloride solution than in pure water. Explain this observation.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Silver chloride dissociates as:

\( \mathrm{AgCl(s) \rightleftharpoons Ag^+(aq) + Cl^-(aq)} \)

Sodium chloride provides extra \( \mathrm{Cl^-} \) ions.

The equilibrium shifts to the left to oppose the increase in chloride ions.

This reduces the solubility of silver chloride.

Example

The solubility product of silver chloride is \( \mathrm{K_{sp} = 1.8 \times 10^{-10}} \).

Calculate the concentration of \( \mathrm{Ag^+} \) ions in a solution that contains \( \mathrm{0.100\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \) chloride ions.

\( \mathrm{AgCl(s) \rightleftharpoons Ag^+(aq) + Cl^-(aq)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Write the solubility product expression:

\( \mathrm{K_{sp} = [Ag^+][Cl^-]} \)

Substitute known values:

\( \mathrm{1.8 \times 10^{-10} = [Ag^+] \times 0.100} \)

Solve for \( \mathrm{[Ag^+]} \):

\( \mathrm{[Ag^+] = 1.8 \times 10^{-9}\ mol\,dm^{-3}} \)

The presence of the common chloride ion greatly reduces the solubility.