CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.4 Covalent bonding and coordinate (dative covalent) bonding Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.4 Covalent bonding and coordinate (dative covalent) bonding Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.4 Covalent bonding and coordinate (dative covalent) bonding Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

- define covalent bonding as electrostatic attraction between the nuclei of two atoms and a shared pair of electrons

(a) describe covalent bonding in molecules including:

• hydrogen, H2

• oxygen, O2

• nitrogen, N2

• chlorine, Cl 2

• hydrogen chloride, HCl

• carbon dioxide, CO2

• ammonia, NH3

• methane, CH4

• ethane, C2H6

• ethene, C2H4

(b) understand that elements in period 3 can expand their octet including in the compounds sulfur dioxide, SO2, phosphorus pentachloride, PCl 5 , and sulfur hexafluoride, SF6

(c) describe coordinate (dative covalent) bonding, including in the reaction between ammonia and hydrogen chloride gases to form the ammonium ion, NH4+ , and in the Al2Cl6 molecule - (a) describe covalent bonds in terms of orbital overlap giving σ and π bonds:

• σ bonds are formed by direct overlap of orbitals between the bonding atoms

• π bonds are formed by the sideways overlap of adjacent p orbitals above and below the σ bond

(b) describe how the σ and π bonds form in molecules including H₂, C₂H₆, C₂H₄, HCN and N₂

(c) use the concept of hybridisation to describe sp, sp² and sp³ orbitals - (a) define the terms:

• bond energy as the energy required to break one mole of a particular covalent bond in the gaseous state

• bond length as the internuclear distance of two covalently bonded atoms

(b) use bond energy values and the concept of bond length to compare the reactivity of covalent molecules

Covalent Bonding

Covalent bonding occurs between non-metal atoms that share electron pairs. The shared electrons experience attraction from the nuclei of both atoms.

Definition of Covalent Bonding

Covalent bonding is the electrostatic attraction between the nuclei of two atoms and a shared pair of electrons.

![]()

- Occurs between non-metals.

- Involves sharing of electrons.

- Produces molecules or giant covalent structures.

Covalent Bonding in Common Molecules

1. Hydrogen — \( \mathrm{H_2} \)

![]()

- Each H atom shares 1 electron.

- One shared pair → single covalent bond.

2. Oxygen — \( \mathrm{O_2} \)

![]()

- Each O atom needs 2 electrons.

- Two shared pairs → double bond.

3. Nitrogen — \( \mathrm{N_2} \)

![]()

- Each N atom needs 3 electrons.

- Three shared pairs → triple bond.

4. Chlorine — \( \mathrm{Cl_2} \)

![]()

- Each Cl atom needs 1 electron.

- One shared pair → single covalent bond.

5. Hydrogen chloride — \( \mathrm{HCl} \)

![]()

- H shares 1 electron; Cl shares 1 electron.

- One shared pair → polar single bond.

6. Carbon dioxide — \( \mathrm{CO_2} \)

![]()

- C forms double bonds with each O atom.

- Two \( \mathrm{C=O} \) double bonds.

- Linear molecule because bond pairs repel symmetrically.

7. Ammonia — \( \mathrm{NH_3} \)

![]()

- N shares electrons with 3 H atoms.

- Three N–H single bonds.

- Lone pair on nitrogen gives trigonal pyramidal shape.

8. Methane — \( \mathrm{CH_4} \)

![]()

- C shares one electron with each H.

- Four C–H single bonds.

- Tetrahedral arrangement.

9. Ethane — \( \mathrm{C_2H_6} \)

- Each C forms 4 single bonds.

- C–C single bond, each C bonded to 3 H atoms.

10. Ethene — \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \)

![]()

- Each C forms a double bond with the other C.

- Each C forms 2 C–H single bonds.

- Planar molecule due to double bond.

Example

How many shared pairs of electrons are present in a molecule of \( \mathrm{O_2} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{O_2} \) contains a double bond → 2 shared electron pairs.

Example

Describe covalent bonding in ammonia, \( \mathrm{NH_3} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

N shares one electron with each of three H atoms.

This forms three N–H single covalent bonds.

The bonding pairs are attracted to both nuclei.

Example

Explain the difference between covalent bonding in ethane \( \mathrm{C_2H_6} \) and ethene \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Ethane: Each carbon forms 4 single bonds → C–C and C–H sigma bonds.

Ethene: Each carbon forms 3 sigma bonds and 1 pi bond → overall a C=C double bond.

The double bond in ethene involves two shared pairs of electrons, while the C–C bond in ethane involves only one shared pair.

(b) Octet Expansion in Period 3 Elements

Octet Expansion

Elements in Period 3 (e.g., S, P) can hold more than 8 electrons in their outer shell because they have accessible empty 3d orbitals. This allows them to form “expanded octet” compounds.

Why Period 3 Can Expand the Octet

- Period 3 elements have the 3d sub-shell available (even though it is empty in ground state).

- These empty 3d orbitals can be used to accommodate extra bonding electrons.

- This allows more than four pairs of electrons around the central atom.

Examples of Expanded Octet Molecules

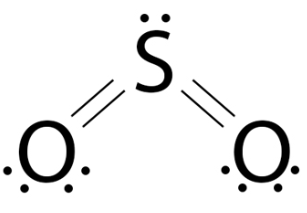

1. Sulfur dioxide — \( \mathrm{SO_2} \)

- Sulfur forms two double bonds with oxygen.

- Total electrons around sulfur = 10 (expanded octet).

- Also shows resonance and a lone pair on S.

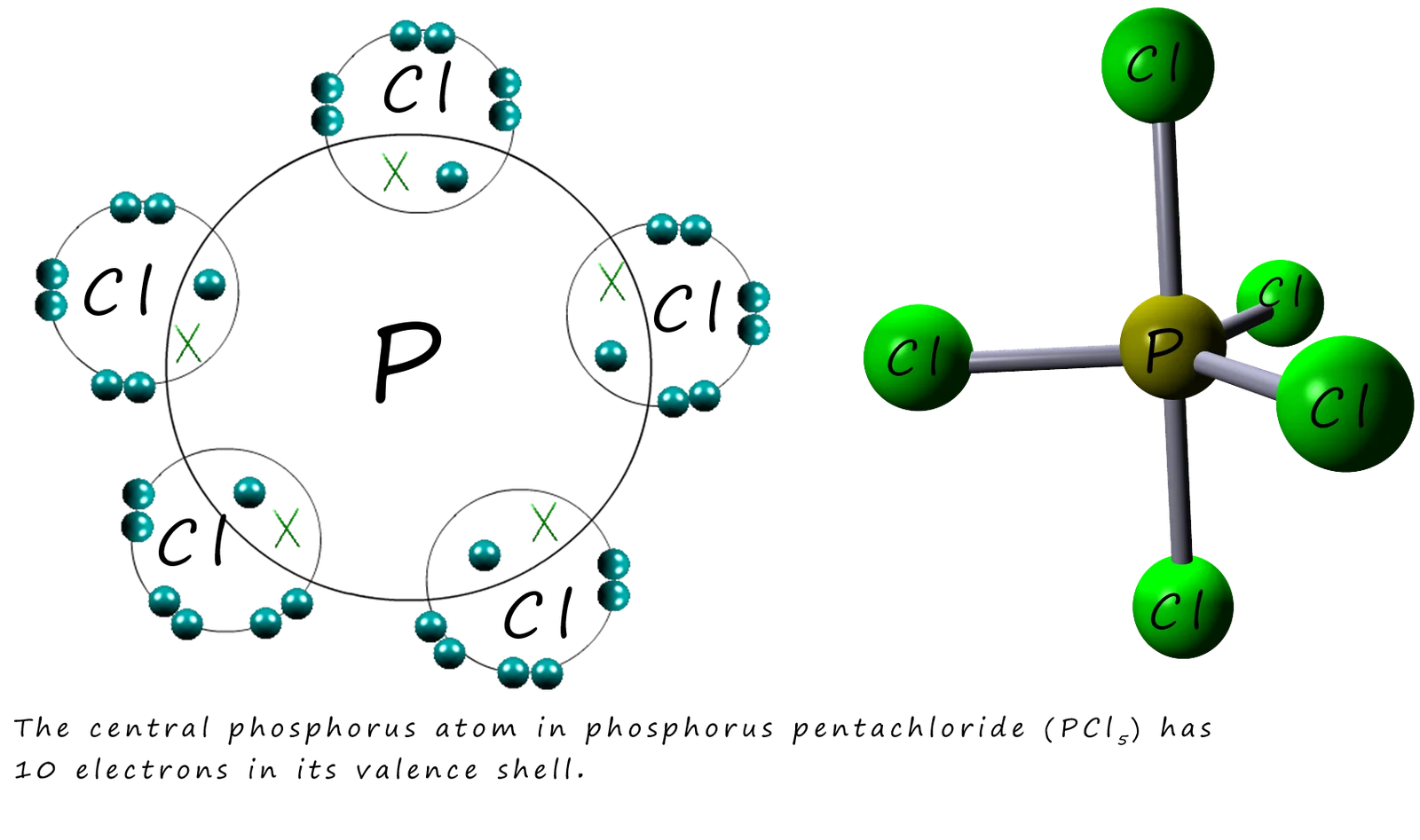

2. Phosphorus pentachloride — \( \mathrm{PCl_5} \)

- P forms 5 single bonds with Cl atoms.

- Total electrons around phosphorus = 10.

- Molecular shape = trigonal bipyramidal.

3. Sulfur hexafluoride — \( \mathrm{SF_6} \)

- S forms 6 S–F single bonds.

- Total electrons around sulfur = 12.

- Shape = octahedral.

- Very stable, often used as an insulating gas.

(c) Coordinate (Dative Covalent) Bonding

Definition of a Coordinate Bond

A coordinate (dative covalent) bond is a covalent bond in which both electrons come from the same atom.

- Still a covalent bond (shared pair).

- Only one atom donates both electrons.

- Usually shown with an arrow → from donor to acceptor.

Examples of Coordinate Bonding

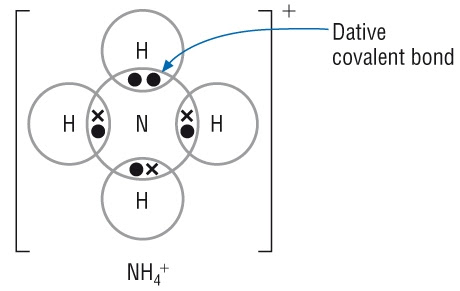

1. Formation of the Ammonium Ion

- Ammonia, \( \mathrm{NH_3} \), has a lone pair on nitrogen.

- Hydrogen chloride forms \( \mathrm{H^+} \) (after dissociation).

- N donates lone pair to \( \mathrm{H^+} \) → forms N→H coordinate bond.

\( \mathrm{NH_3 + H^+ \rightarrow NH_4^+} \)

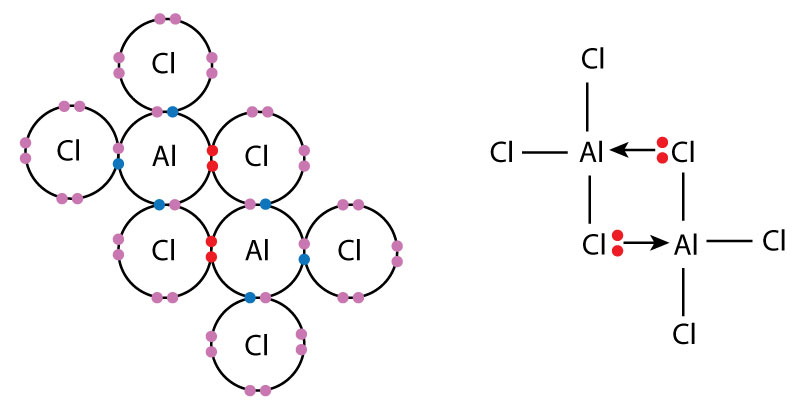

2. Dimerisation of Aluminium Chloride

- AlCl\(_3\) has an electron-deficient Al atom (only 6 electrons around it).

- Chlorine atoms with lone pairs donate electrons to the Al of another molecule.

- This forms two Al←Cl coordinate bonds, giving the dimer \( \mathrm{Al_2Cl_6} \).

Example

Explain how a coordinate bond forms in \( \mathrm{NH_4^+} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Nitrogen in \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) has a lone pair of electrons.

The \( \mathrm{H^+} \) ion has no electrons.

N donates its lone pair to \( \mathrm{H^+} \), forming a coordinate bond.

Bond shown as N→H.

Example

Explain why sulfur can form six bonds in \( \mathrm{SF_6} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Sulfur is a Period 3 element and has empty 3d orbitals available.

These orbitals can accommodate extra electrons beyond the octet.

Thus sulfur can form 6 S–F bonds, giving 12 electrons around S.

Example

Describe how coordinate bonds form in \( \mathrm{Al_2Cl_6} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Each \( \mathrm{AlCl_3} \) unit has an electron-deficient Al atom (only 6 valence electrons).

Two Cl atoms from neighbouring molecules each donate a lone pair to an Al atom.

This forms two Al←Cl dative covalent bonds.

The molecule dimerises to form \( \mathrm{Al_2Cl_6} \).

Sigma (σ) and Pi (π) Bonds — Orbital Overlap

Covalent bonds are formed by the overlap of atomic orbitals. The way the orbitals overlap determines whether the bond is a sigma (\( \sigma \)) or pi (\( \pi \)) bond.

Sigma (\( \sigma \)) Bonds

Definition: A \( \sigma \) bond is formed by direct overlap of orbitals along the internuclear axis.

![]()

- Formed by direct (head-on) overlap of orbitals.

- Overlap can be between: – two \( \mathrm{s} \) orbitals – an \( \mathrm{s} \) and a \( \mathrm{p} \) orbital – two \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals (end-to-end)

- All single bonds are σ bonds.

- σ bonds have electron density directly between the nuclei → strongest type of covalent bond.

Pi (\( \pi \)) Bonds

Definition: A \( \pi \) bond is formed by the sideways overlap of parallel \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals above and below the σ bond.

![]()

- Formed by sideways overlap of adjacent \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals.

- Electron density lies above and below the plane of the σ bond.

- A \( \pi \) bond can only form after a σ bond is present.

- Double bond = 1 σ + 1 π

- Triple bond = 1 σ + 2 π

- π bonds are weaker than σ bonds because the overlap is less effective.

| Bond Type | How It Forms | Location of Electron Density | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \sigma \) bond | Direct (head-on) overlap | Between the nuclei | Strong |

| \( \pi \) bond | Sideways overlap of \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals | Above and below the σ bond | Weaker |

Example

How many σ and π bonds are present in an \( \mathrm{O_2} \) molecule?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{O_2} \) has a double bond.

Double bond = 1 σ + 1 π

Therefore: 1 σ bond and 1 π bond.

Example

Describe how the π bond in ethene \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \) is formed.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Each carbon atom forms three σ bonds (two C–H and one C–C), using hybridised orbitals.

The unhybridised \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals on each carbon remain parallel.

These \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals overlap sideways above and below the σ bond.

This sideways overlap forms the π bond.

Example

Explain why the triple bond in \( \mathrm{N_2} \) consists of one σ bond and two π bonds.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The σ bond forms from direct overlap of \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals along the internuclear axis.

The remaining two pairs of electrons occupy parallel \( \mathrm{p} \) orbitals on each N atom.

These overlap sideways → forming two π bonds.

Total: 1 σ + 2 π bonds in \( \mathrm{N_2} \).

2. σ and π Bond Formation in Required Molecules

\( \mathrm{H_2} \)

- Each H atom has one \( 1s \) orbital.

- The \( 1s + 1s \) orbitals overlap end-to-end.

- Forms a single σ bond.

\( \mathrm{C_2H_6} \) (Ethane)

![]()

- C atoms use \( \mathrm{sp^3} \) hybrid orbitals.

- C–C bond: σ bond from \( \mathrm{sp^3 – sp^3} \) overlap.

- C–H bonds: σ bonds from \( \mathrm{sp^3 – 1s} \) overlap.

- Only σ bonds → no π bonds.

\( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \) (Ethene)

- C atoms use \( \mathrm{sp^2} \) hybrid orbitals.

- C–C σ bond: \( \mathrm{sp^2 – sp^2} \) overlap.

- Each C has an unhybridised \( p \) orbital → sideways overlap → π bond.

- C–H bonds: σ from \( \mathrm{sp^2 – 1s} \).

- Double bond = 1 σ + 1 π.

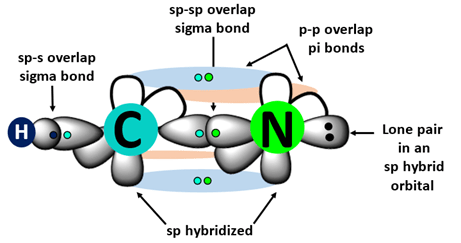

\( \mathrm{HCN} \) (Hydrogen cyanide)

- C and N both use \( \mathrm{sp} \) hybrid orbitals for the C≡N axis.

- C–N σ bond: \( \mathrm{sp – sp} \) overlap.

- Two unhybridised \( p \) orbitals on each atom overlap sideways → 2 π bonds.

- C–H σ bond: \( \mathrm{sp – 1s} \).

- Triple bond = 1 σ + 2 π.

\( \mathrm{N_2} \)

- Each N atom uses \( \mathrm{sp} \) hybrid orbitals.

- One \( \mathrm{sp – sp} \) overlap forms the σ bond.

- Two unhybridised \( p \) orbitals overlap sideways → 2 π bonds.

- N≡N contains 1 σ and 2 π bonds.

Example

How many σ bonds are present in \( \mathrm{C_2H_6} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Ethane has:

- 1 C–C σ bond

- 6 C–H σ bonds

Total = 7 σ bonds

Example

Explain how the σ and π bonds form in \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Each carbon uses \( \mathrm{sp^2} \) hybrid orbitals.

σ bond (C–C): from \( \mathrm{sp^2 – sp^2} \) overlap.

π bond: from sideways overlap of unhybridised \( p \) orbitals.

C–H bonds: \( \mathrm{sp^2 – 1s} \) overlaps forming σ bonds.

Double bond = 1 σ + 1 π.

Example

Describe all σ and π bonds in \( \mathrm{HCN} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

C and N are \( \mathrm{sp} \) hybridised.

σ bonds: – \( \mathrm{sp – sp} \) between C and N – \( \mathrm{sp – 1s} \) between C and H

π bonds: Two unhybridised \( p \) orbitals on C and N overlap sideways → 2 π bonds.

Total bonds: C≡N = 1 σ + 2 π C–H = 1 σ

Hybridisation — \( \mathrm{sp} \), \( \mathrm{sp^2} \), \( \mathrm{sp^3} \) Orbitals

Hybridisation is the mixing of atomic orbitals to form new hybrid orbitals that are identical in energy and shape. These hybrid orbitals explain molecular shapes and the formation of σ and π bonds.

1. \( \mathrm{sp}^3 \) Hybridisation

![]()

How it forms

- One \( s \) orbital mixes with three \( p \) orbitals → four \( \mathrm{sp^3} \) hybrid orbitals.

- All orbitals are identical and arranged tetrahedrally.

Geometry: Tetrahedral Bond angle: \( 109.5^\circ \)

Examples: methane \( \mathrm{CH_4} \), ethane \( \mathrm{C_2H_6} \).

σ bonds: \( \mathrm{sp^3 – sp^3} \), \( \mathrm{sp^3 – 1s} \)

2. \( \mathrm{sp}^2 \) Hybridisation

![]()

How it forms

- One \( s \) orbital mixes with two \( p \) orbitals → three \( \mathrm{sp^2} \) hybrid orbitals.

- One unhybridised \( p \) orbital remains → forms π bonds.

Geometry: Trigonal planar Bond angle: \( 120^\circ \)

Examples: ethene \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \), \( \mathrm{BF_3} \).

σ bonds: \( \mathrm{sp^2 – sp^2} \), \( \mathrm{sp^2 – 1s} \) π bond: sideways overlap of the unhybridised \( p \) orbitals

3.\( \mathrm{sp} \) Hybridisation

![]()

How it forms

- One \( s \) and one \( p \) orbital mix → two \( \mathrm{sp} \) hybrid orbitals.

- Two unhybridised \( p \) orbitals remain → can form two π bonds.

Geometry: Linear Bond angle: \( 180^\circ \)

Examples: ethyne \( \mathrm{C_2H_2} \), hydrogen cyanide \( \mathrm{HCN} \), nitrogen \( \mathrm{N_2} \).

σ bonds: \( \mathrm{sp – sp} \), \( \mathrm{sp – 1s} \) π bonds: from two unhybridised orthogonal \( p \) orbitals

| Hybridisation | Orbitals Mixed | No. of Hybrid Orbitals | Geometry | Bond Angle | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{sp^3} \) | 1s + 3p | 4 | Tetrahedral | \( 109.5^\circ \) | \( \mathrm{CH_4} \) |

| \( \mathrm{sp^2} \) | 1s + 2p | 3 | Trigonal planar | \( 120^\circ \) | \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \) |

| \( \mathrm{sp} \) | 1s + 1p | 2 | Linear | \( 180^\circ \) | \( \mathrm{HCN} \), \( \mathrm{N_2} \) |

Example

What is the hybridisation state of carbon in methane \( \mathrm{CH_4} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Carbon mixes one \( s \) and three \( p \) orbitals → \( \mathrm{sp^3} \) hybridisation.

Geometry is tetrahedral, \( 109.5^\circ \).

Example

Explain why ethene \( \mathrm{C_2H_4} \) has a trigonal planar geometry around each carbon.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Each carbon forms \( \mathrm{sp^2} \) hybrid orbitals (mixing 1s and 2p).

These three hybrid orbitals arrange themselves \( 120^\circ \) apart → trigonal planar.

The remaining unhybridised \( p \) orbitals form the π bond.

Example

Describe all σ and π bonds formed in hydrogen cyanide \( \mathrm{HCN} \) using hybridisation theory.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Carbon and nitrogen are both \( \mathrm{sp} \) hybridised → linear geometry.

σ bonds:

- C–N σ bond: \( \mathrm{sp – sp} \)

- C–H σ bond: \( \mathrm{sp – 1s} \)

π bonds:

- Two unhybridised \( p \) orbitals on C and N overlap sideways → 2 π bonds

Total: C≡N = 1 σ + 2 π C–H = 1 σ

Bond Energy and Bond Length

Covalent bonds have measurable properties such as the energy needed to break them and the distance between the bonded nuclei. These properties help predict molecular strength, stability, and reactivity.

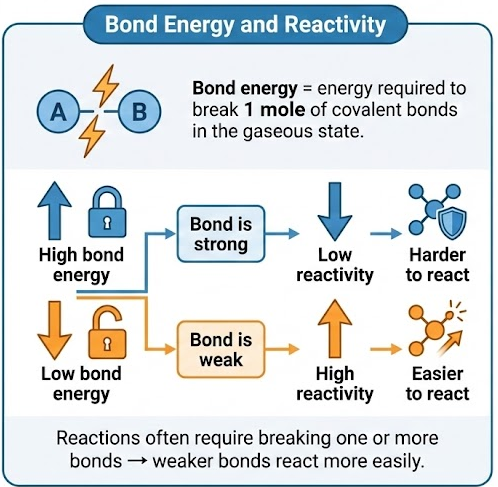

Bond Energy

Bond energy is defined as: “The energy required to break one mole of a particular covalent bond in the gaseous state.”

- Units: \( \mathrm{kJ\ mol^{-1}} \)

- Always positive, because breaking bonds requires energy.

- Higher bond energy = stronger bond.

- Values depend on the specific molecule (e.g., C–H in methane vs ethane).

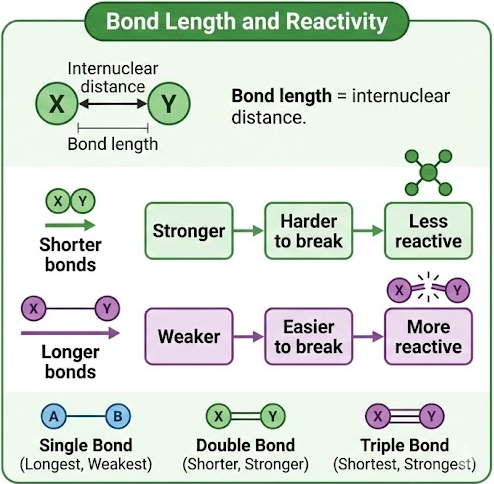

Bond Length

Bond length is defined as: “The internuclear distance between two covalently bonded atoms.”

- Measured in \( \mathrm{pm} \) (picometres) or \( \mathrm{\AA} \).

- Shorter bond → stronger bond (generally).

- Bond length decreases from single → double → triple bonds.

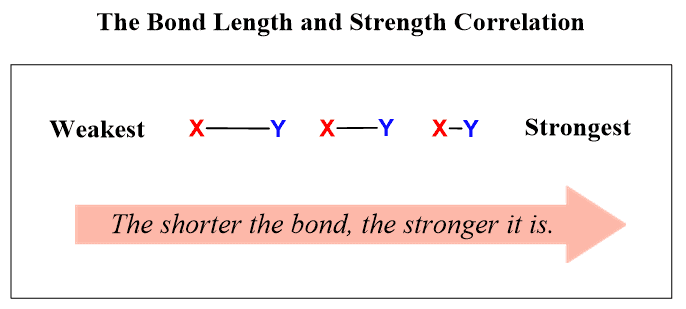

Relationship Between Bond Energy and Bond Length

- Short bond = stronger → high bond energy (e.g., C≡C).

- Long bond = weaker → lower bond energy (e.g., C–C).

Example

Define bond length.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Bond length is the internuclear distance between two covalently bonded atoms.

Example

Explain why a C≡C bond has a higher bond energy and shorter bond length than a C–C bond.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A C≡C triple bond has more shared electron density and stronger attraction between nuclei compared with a C–C single bond.

This makes the C≡C bond shorter and stronger → higher bond energy.

Example

Explain why the O–H bond in water has a higher bond energy than the S–H bond in hydrogen sulfide.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Oxygen is smaller and more electronegative than sulfur.

- Shorter O–H bond → stronger attraction → higher bond energy.

- S–H bond is longer because sulfur has a larger atomic radius → weaker → lower bond energy.

Therefore, \( \mathrm{O–H} \) has higher bond energy than \( \mathrm{S–H} \).

Bond Energies, Bond Length and Reactivity of Covalent Molecules

The reactivity of a covalent molecule depends strongly on the strength and length of its bonds. Bond energy tells us how much energy is needed to break a bond, while bond length shows how close the bonded nuclei are. Together, these determine how easily a molecule reacts.

Bond Energy and Reactivity

- Bond energy = energy required to break 1 mole of covalent bonds in the gaseous state.

- High bond energy → bond is strong → low reactivity.

- Low bond energy → bond is weak → high reactivity.

- Reactions often require breaking one or more bonds → weaker bonds react more easily.

Bond Length and Reactivity

- Bond length = internuclear distance.

- Shorter bonds → stronger → harder to break → less reactive.

- Longer bonds → weaker → easier to break → more reactive.

- Single bonds are longest (weakest), triple bonds are shortest (strongest).

General Patterns

- \( \mathrm{C–I} \) is more reactive than \( \mathrm{C–Br} \), \( \mathrm{C–Cl} \), \( \mathrm{C–F} \) because it has the longest, weakest bond.

- \( \mathrm{O=O} \) is more reactive than \( \mathrm{N \equiv N} \) because the nitrogen triple bond has an extremely high bond energy.

- Alkanes (C–C and C–H single bonds) are less reactive than alkenes, which contain a weaker \( \pi \) bond.

Example

Which bond is easier to break: \( \mathrm{C–I} \) or \( \mathrm{C–F} \)? Explain.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{C–I} \) is easier to break because it is longer and therefore weaker.

\( \mathrm{C–F} \) is short and strong → higher bond energy → less reactive.

Example

Bond energies: \( \mathrm{H–H} = 436\ kJ\ mol^{-1} \), \( \mathrm{Cl–Cl} = 243\ kJ\ mol^{-1} \). Which molecule, \( \mathrm{H_2} \) or \( \mathrm{Cl_2} \), is more reactive?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{Cl–Cl} \) has a much lower bond energy than \( \mathrm{H–H} \).

Weaker bond → easier to break → \( \mathrm{Cl_2} \) is more reactive than \( \mathrm{H_2} \).

Example

Explain why alkenes are more reactive than alkanes using bond energy and bond length ideas.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Alkenes contain a \( \mathrm{C=C} \) double bond, consisting of a σ bond and a π bond.

- The π bond has lower bond energy and is weaker than a σ bond.

- It is located above and below the internuclear axis, making it more exposed to attack by reagents.

- Breaking the π bond requires less energy than breaking a σ bond (such as in alkanes with only C–C σ bonds).

Therefore, alkenes are more reactive because they contain a weaker, more accessible π bond.