CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.6 Intermolecular forces, electronegativity and bond properties Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.6 Intermolecular forces, electronegativity and bond properties Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 3.6 Intermolecular forces, electronegativity and bond properties Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

- (a) describe hydrogen bonding, limited to molecules containing N–H and O–H groups, including ammonia and water as simple examples

(b) use the concept of hydrogen bonding to explain the anomalous properties of H₂O (ice and water):

• its relatively high melting and boiling points

• its relatively high surface tension

• the density of the solid ice compared with the liquid water - use the concept of electronegativity to explain bond polarity and dipole moments of molecules

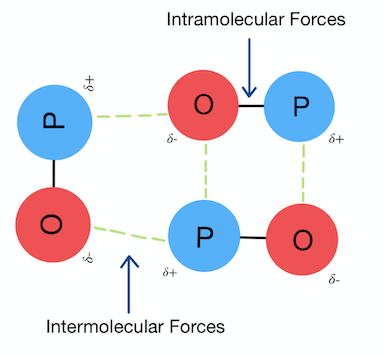

- (a) describe van der Waals’ forces as the intermolecular forces between molecular entities other than those due to bond formation, and use the term van der Waals’ forces as a generic term to describe all intermolecular forces

(b) describe the types of van der Waals’ forces:

• instantaneous dipole–induced dipole (id-id) forces, also called London dispersion forces

• permanent dipole–permanent dipole (pd-pd) forces, including hydrogen bonding

(c) describe hydrogen bonding and understand that hydrogen bonding is a special case of permanent dipole–permanent dipole forces between molecules where hydrogen is bonded to a highly electronegative atom - state that, in general, ionic, covalent and metallic bonding are stronger than intermolecular forces

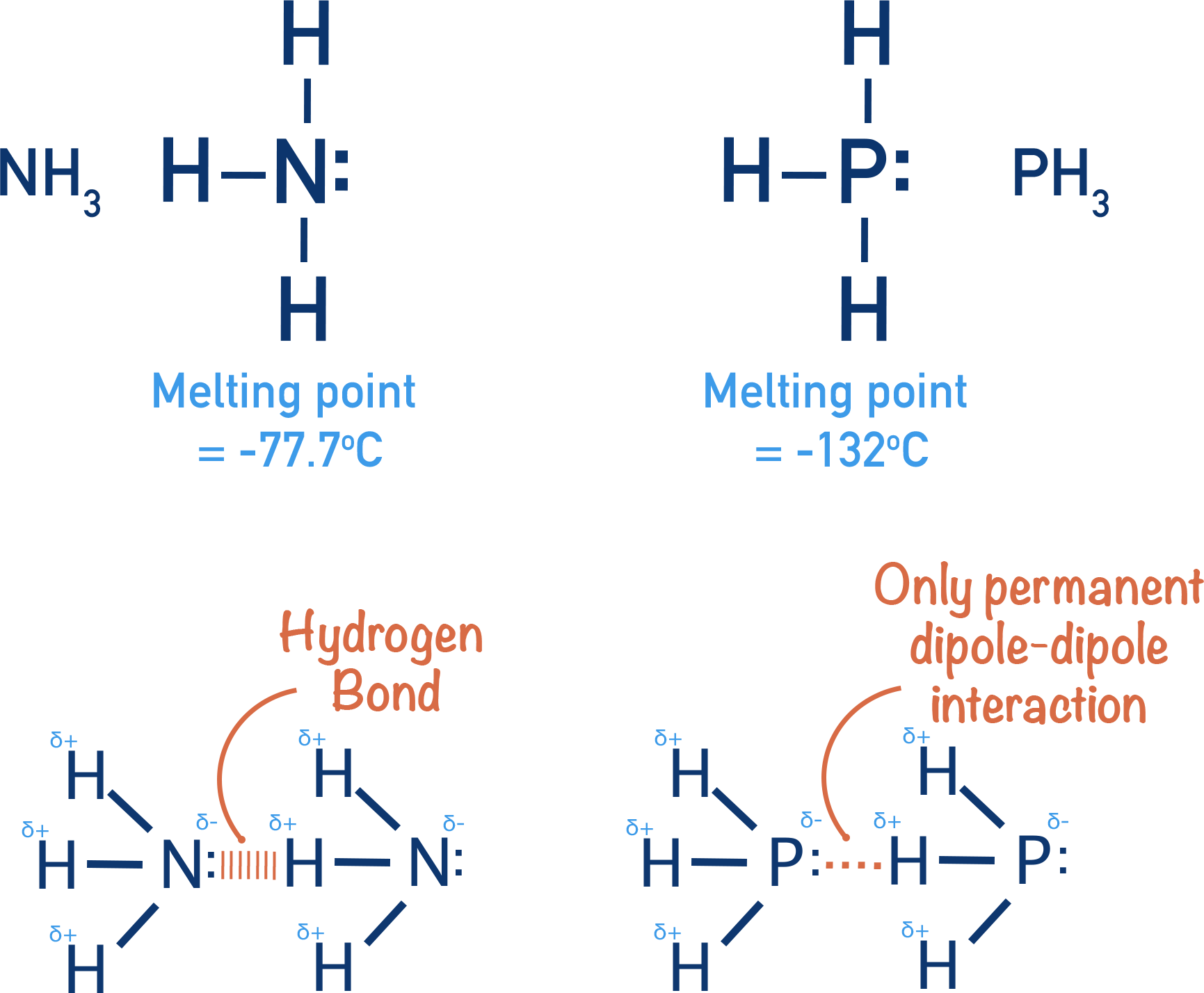

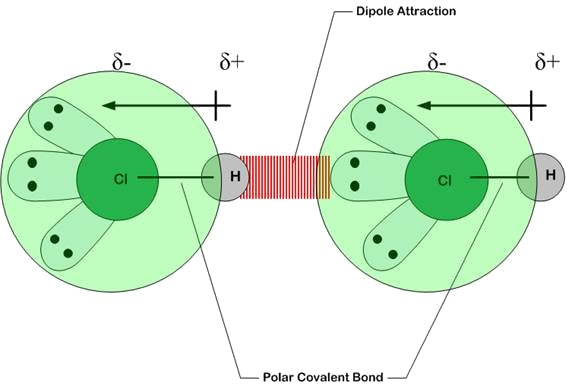

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is the strongest type of intermolecular force. It occurs when a hydrogen atom bonded to a highly electronegative atom forms an attraction with a lone pair on another electronegative atom.

Definition of Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding is a strong intermolecular attraction between:

1. A hydrogen atom covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom (N or O), and

2. A lone pair on an electronegative atom (N or O) in a neighbouring molecule.

Occurs in molecules containing \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) groups.

Why Hydrogen Bonding Occurs

- N and O have very high electronegativity → they pull electron density away from H.

- This gives hydrogen a strong partial positive charge \( (\delta^+) \).

- The electronegative atom has a lone pair with a partial negative charge \( (\delta^-) \).

- Attraction between \( \delta^+ \) H and lone pair produces a hydrogen bond.

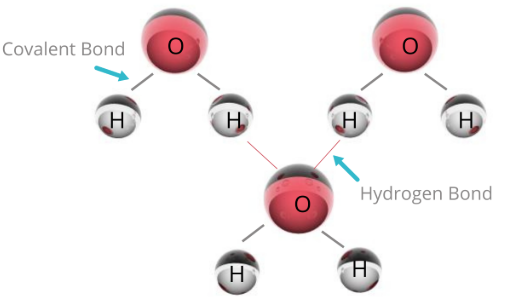

Hydrogen Bonding in Water (\( \mathrm{H_2O} \))

- Oxygen is very electronegative and has two lone pairs.

- Each water molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds.

- Strong hydrogen bonding explains: – high boiling point – high surface tension – solid water (ice) being less dense than liquid water

Hydrogen bond: \( \mathrm{O\!-\!H\ \delta^+ \cdots \delta^-\ O} \)

Hydrogen Bonding in Ammonia (\( \mathrm{NH_3} \))

- Nitrogen is highly electronegative and has one lone pair.

- Hydrogen bonding occurs between the lone pair on one N and the \( \delta^+ \) H on another molecule.

- Each ammonia molecule forms fewer hydrogen bonds than water → weaker overall hydrogen bonding.

Hydrogen bond: \( \mathrm{N\!-\!H\ \delta^+ \cdots \delta^-\ N} \)

| Molecule | Group Required | Lone Pairs | Hydrogen Bonding Present? |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{H_2O} \) | \( \mathrm{O–H} \) | 2 | Yes (strong) |

| \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) | \( \mathrm{N–H} \) | 1 | Yes (weaker than water) |

| \( \mathrm{CH_4} \) | No N–H / O–H | None | No hydrogen bonding |

Example

Does ammonia form hydrogen bonds? Explain.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Yes. \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) contains \( \mathrm{N–H} \) bonds and N has a lone pair. The lone pair on one molecule is attracted to the \( \delta^+ \) H on another molecule.

Example

Why does water form stronger hydrogen bonds than ammonia?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Oxygen is more electronegative than nitrogen → gives H a stronger \( \delta^+ \).

Water also has two lone pairs and two \( \mathrm{O–H} \) bonds → can form up to four hydrogen bonds per molecule.

Ammonia has only one lone pair and forms fewer hydrogen bonds.

Example

Which forms stronger hydrogen bonding: \( \mathrm{H_2O} \) or \( \mathrm{HF} \)? Explain using electronegativity and number of bonds.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{HF} \) has the most electronegative atom (F), so each individual H-bond is strong.

However, each HF molecule can form only one hydrogen bond (1 H, 3 lone pairs).

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) can form up to four hydrogen bonds per molecule (2 lone pairs + 2 H atoms).

Therefore, water has stronger overall hydrogen bonding due to more extensive hydrogen bond networks.

Hydrogen Bonding and the Anomalous Properties of Water (Ice and Liquid Water)

Water exhibits several unusual (anomalous) physical properties. These arise from the extensive hydrogen bonding between water molecules due to the highly polar \( \mathrm{O–H} \) bond and the ability of each molecule to form up to four hydrogen bonds.

1. High Melting and Boiling Points

Water has higher melting and boiling points than other hydrides of Group 16 (e.g., \( \mathrm{H_2S} \), \( \mathrm{H_2Se} \)).

- Each water molecule forms up to four hydrogen bonds.

- Hydrogen bonds are much stronger than other intermolecular forces (e.g., dipole–dipole, London forces).

- A large amount of energy is needed to break these hydrogen bonds.

Therefore, water has unusually high melting and boiling points.

2. High Surface Tension

Water has one of the highest surface tensions of any common liquid.

- At the surface, water molecules form stronger hydrogen-bond networks with molecules beside and below them.

- This creates a “skin-like” effect where the surface resists being stretched or broken.

- Cohesion between water molecules is strong because of hydrogen bonding.

Result: high surface tension → droplets form spheres, insects can walk on water, etc.

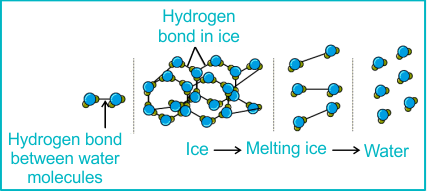

3. Density of Ice vs Liquid Water

Unusually, solid ice is less dense than liquid water — so ice floats.

- When water freezes, hydrogen bonds arrange molecules into an open hexagonal lattice.

- This structure maximises hydrogen bonding but leaves large empty spaces.

- As a result, molecules are further apart in ice than in liquid water.

Ice has lower density than water → floats on water.

| Property | Explanation (Hydrogen Bonding) |

|---|---|

| High melting & boiling points | Many strong hydrogen bonds require large energy to break. |

| High surface tension | Strong cohesive forces between surface molecules due to hydrogen bonding. |

| Ice less dense than water | Hydrogen bonds create an open hexagonal lattice with large spaces → lower density. |

Example

Why does liquid water have a higher boiling point than \( \mathrm{H_2S} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{H_2O} \) forms hydrogen bonds, which are much stronger than the weak intermolecular forces in \( \mathrm{H_2S} \).

Much more energy is needed to break hydrogen bonds → higher boiling point.

Example

Explain why water has a high surface tension using hydrogen bonding.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

At the surface, water molecules form stronger hydrogen-bond networks with neighbouring molecules.

This creates strong cohesive forces, giving water a high surface tension.

Example

Explain why ice floats on water using hydrogen bonding and molecular arrangement.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

In ice, hydrogen bonds fix the water molecules into an open hexagonal lattice.

This structure increases the distance between molecules, creating empty space and reducing density.

Liquid water has a more compact arrangement because hydrogen bonds are constantly breaking and reforming.

Thus, ice is less dense and floats.

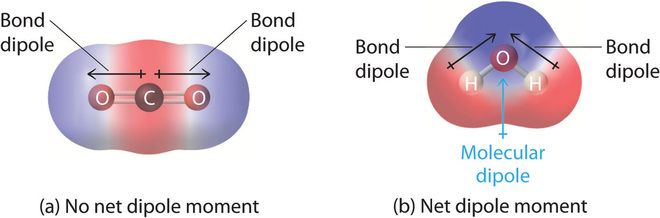

Bond Polarity and Dipole Moments Using Electronegativity

Electronegativity differences between atoms cause unequal sharing of electrons in a covalent bond. This creates bond polarity and may produce a molecular dipole moment depending on the arrangement of the bonds.

Bond Polarity

A covalent bond becomes polar when the two atoms involved have different electronegativities.

- The atom with higher electronegativity attracts the shared electrons more strongly.

- This atom becomes partially negative \( (\delta^-) \).

- The less electronegative atom becomes partially positive \( (\delta^+) \).

- A dipole is formed → shown as \( \mathrm{\delta^+ -\!\!\!\!\rightarrow\ \delta^-} \).

Bond polarity increases with increasing electronegativity difference.

Dipole Moments of Molecules

A molecule’s dipole moment depends on both the polarity of its bonds and its molecular shape.

- If polar bond dipoles do not cancel out → molecule has a net dipole moment (polar molecule).

- If polar bond dipoles cancel out due to symmetry → molecule is non-polar, even if it contains polar bonds.

Effect of Shape on Dipole Moments

| Molecule | Bond Polarity | Shape | Molecular Dipole? |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{CO_2} \) | C=O bonds polar | Linear | No (dipoles cancel) |

| \( \mathrm{H_2O} \) | O–H bonds polar | V-shaped | Yes (dipoles add) |

| \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) | N–H polar | Pyramidal | Yes |

| \( \mathrm{CH_4} \) | C–H slightly polar | Tetrahedral | No (symmetrical) |

Example

Which bond is more polar: \( \mathrm{C–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \)? Explain.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Oxygen is far more electronegative than carbon or hydrogen.

Electronegativity difference is largest in \( \mathrm{O–H} \), so it is the more polar bond.

Example

Explain why \( \mathrm{CO_2} \) is non-polar even though it contains polar bonds.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The C=O bonds are polar and have dipoles pointing in opposite directions.

The linear shape means the dipoles are equal and opposite → they cancel out.

Therefore \( \mathrm{CO_2} \) has no overall dipole moment (non-polar).

Example

Explain why \( \mathrm{H_2O} \) has a larger dipole moment than \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) even though both are polar molecules.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Oxygen is more electronegative than nitrogen, so the \( \mathrm{O–H} \) bond is more polar than the \( \mathrm{N–H} \) bond.

The bent shape of water (104.5°) causes its bond dipoles to combine more strongly, giving a larger net dipole moment.

Ammonia is pyramidal (107°), and its dipoles do not reinforce as strongly.

Therefore, \( \mathrm{H_2O} \) has a larger dipole moment than \( \mathrm{NH_3} \).

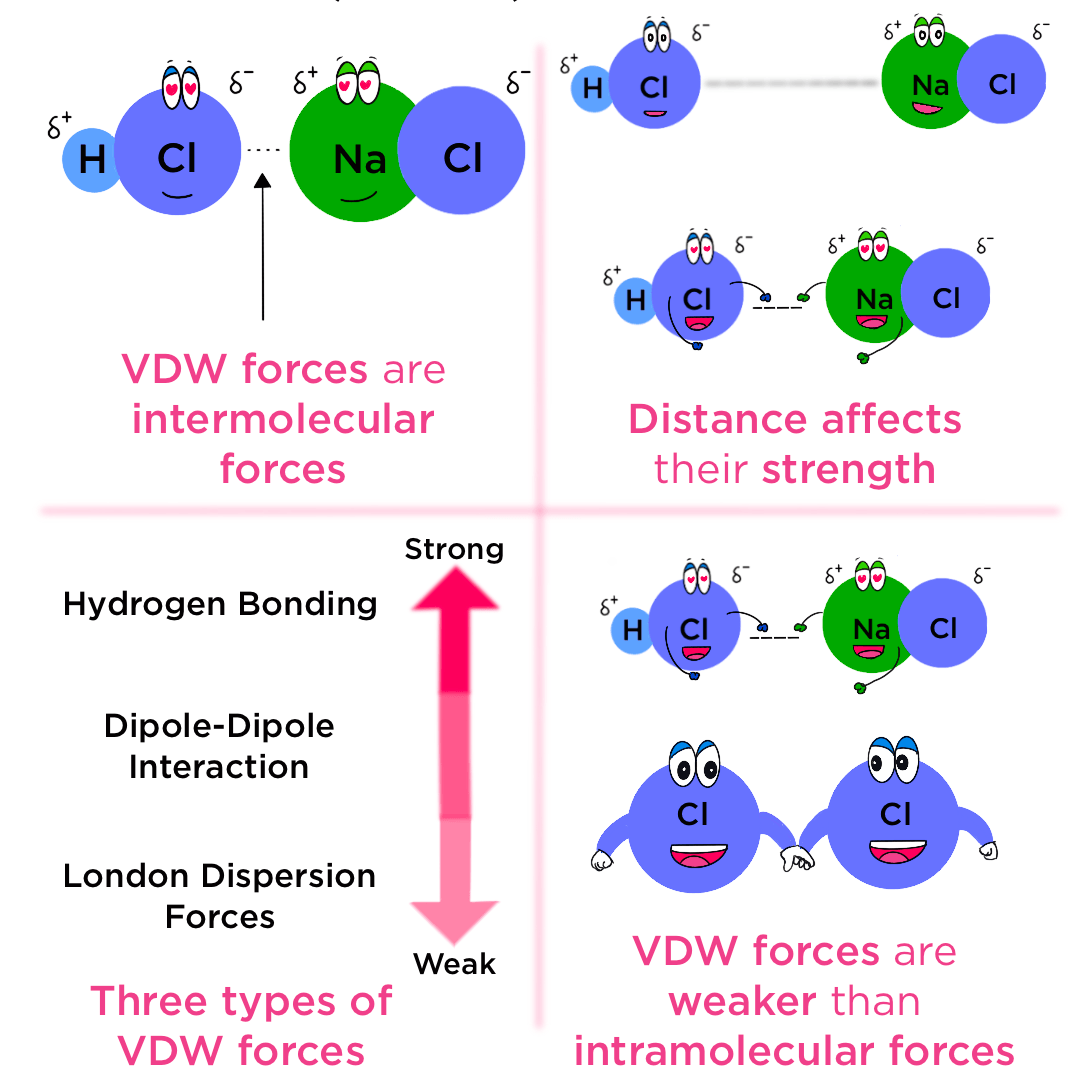

Van der Waals’ Forces — Definition and Use

Van der Waals’ forces are all intermolecular forces that occur between molecules, apart from those involving bond formation (i.e., not covalent, ionic, or metallic bonds). They include London dispersion forces, permanent dipole–dipole forces, and hydrogen bonding.

Definition of Van der Waals’ Forces

Van der Waals’ forces are the intermolecular forces between molecular entities other than those due to bond formation.

The term van der Waals’ forces is used as a generic term to describe all intermolecular forces.

Types of Intermolecular Forces Included Under Van der Waals’ Forces

| Type of Intermolecular Force | Description | Included as Van der Waals? |

|---|---|---|

| London dispersion forces | Caused by temporary dipoles from electron movement. | Yes |

| Permanent dipole–dipole forces | Attraction between permanent molecular dipoles. | Yes |

| Hydrogen bonding | Strong dipole–dipole attraction involving \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \). | Yes |

| Ionic, covalent, metallic bonds | Involve bond formation, not intermolecular. | No |

Example

Which type of force is described by the term “van der Waals’ forces”?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

It is a generic term that refers to all intermolecular forces, including London dispersion forces, dipole–dipole forces, and hydrogen bonding.

Example

Explain why hydrogen bonding is considered a type of van der Waals’ force.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Hydrogen bonding is an intermolecular attraction (not a bond) and occurs between molecules.

Since van der Waals’ forces include all intermolecular forces, hydrogen bonding is counted as a strong form of van der Waals’ force.

Example

Explain why ionic bonds are not classified as van der Waals’ forces, whereas dipole–dipole forces are.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Ionic bonds involve full electrostatic attraction between ions and result from bond formation.

This makes them intramolecular forces, not intermolecular forces.

Dipole–dipole forces occur between separate molecules without forming bonds and are therefore intermolecular.

Because van der Waals’ forces refer specifically to intermolecular forces, ionic bonds are excluded while dipole–dipole forces are included.

Types of Van der Waals’ Forces

Van der Waals’ forces include all intermolecular forces that occur between molecules. These can be classified into three main types: instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces (London dispersion forces), permanent dipole–permanent dipole forces, and hydrogen bonding.

1. Instantaneous Dipole–Induced Dipole Forces (id–id)

Also called: London dispersion forces

- Present in all molecules (polar and non-polar).

- Caused by random movement of electrons → creates a temporary dipole.

- This temporary dipole induces a dipole in a neighbouring molecule → weak attraction.

- Strength increases with:

- number of electrons

- molar mass

- surface area / contact area

Greater electrons → stronger London forces → higher boiling point.

2. Permanent Dipole–Permanent Dipole Forces (pd–pd)

- Occurs between molecules with permanent dipoles.

- Bonds are polar because of electronegativity differences.

- The positive end of one polar molecule attracts the negative end of another.

- Stronger than London forces, but weaker than hydrogen bonding.

Example: \( \mathrm{HCl} \), \( \mathrm{CH_3Cl} \), \( \mathrm{C=O} \)-containing molecules.

3. Hydrogen Bonding (a special type of pd–pd force)

- Strongest type of van der Waals’ force.

- Occurs when H is bonded to highly electronegative atoms: \( \mathrm{N, O} \).

- Requires:

- a \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) bond

- a lone pair on an electronegative atom

- Examples: \( \mathrm{H_2O} \), \( \mathrm{NH_3} \), alcohols, amines.

Hydrogen bond: \( \mathrm{\delta^+ H \cdots \delta^- O} \) or \( \mathrm{\delta^+ H \cdots \delta^- N} \)

Comparison Table

| Force Type | Cause | Strength | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| id–id (London) | Temporary dipoles from electron movement | Weakest | \( \mathrm{I_2} \), \( \mathrm{CH_4} \), noble gases |

| pd–pd | Attraction between permanent dipoles | Medium | \( \mathrm{HCl} \), \( \mathrm{CH_3Cl} \) |

| Hydrogen bonding | \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) + lone pairs | Strongest | \( \mathrm{H_2O} \), \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) |

Example

What type of intermolecular force exists between \( \mathrm{CH_4} \) molecules?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{CH_4} \) is non-polar, so only instantaneous dipole–induced dipole (London dispersion) forces act between its molecules.

Example

Explain why \( \mathrm{HCl} \) has stronger intermolecular forces than \( \mathrm{F_2} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{HCl} \) has a permanent dipole because Cl is much more electronegative than H.

Therefore, pd–pd forces exist between \( \mathrm{HCl} \) molecules, which are stronger than the London forces in non-polar \( \mathrm{F_2} \).

Example

Explain why ethanol (\( \mathrm{CH_3CH_2OH} \)) has a higher boiling point than dimethyl ether (\( \mathrm{CH_3OCH_3} \)), even though they have the same molecular formula.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Ethanol contains an \( \mathrm{O–H} \) group, so it forms hydrogen bonds between molecules.

Dimethyl ether has an \( \mathrm{O} \) atom but no \( \mathrm{O–H} \) bond → it cannot hydrogen bond.

Dimethyl ether only has pd–pd and London forces, which are weaker.

Therefore ethanol has a much higher boiling point due to hydrogen bonding.

Hydrogen Bonding as a Special Case of Permanent Dipole–Permanent Dipole Forces

Hydrogen bonding is the strongest type of intermolecular attraction. It is a special type of permanent dipole–permanent dipole (pd–pd) force that occurs only when hydrogen is bonded to a highly electronegative atom: nitrogen or oxygen.

What is Hydrogen Bonding?

- Occurs when H is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom:

- \( \mathrm{N–H} \)

- \( \mathrm{O–H} \)

- The electronegative atom pulls electron density away from hydrogen → H becomes strongly partially positive \( (\delta^+) \).

- The electronegative atom has a lone pair that carries partial negative charge \( (\delta^-) \).

- A strong attraction forms between:

- \( \delta^+ \) hydrogen on one molecule

- lone pair on \( \mathrm{N} \) or \( \mathrm{O} \) of another molecule

Hydrogen bond: \( \mathrm{\delta^+H\ \cdots\ \delta^-O} \) or \( \mathrm{\delta^+H\ \cdots\ \delta^-N} \)

Why It Is a Special Case of pd–pd Forces

- Hydrogen bonding is a very strong permanent dipole–permanent dipole force.

- It is stronger than other pd–pd forces because:

- \( \mathrm{N} \) and \( \mathrm{O} \) are extremely electronegative

- The small size of H allows very close approach of molecules

- Large dipole created when electrons are pulled strongly from H

- Thus, hydrogen bonding is simply an extreme, strong form of pd–pd interaction.

Where Hydrogen Bonding Occurs

Occurs only when hydrogen is bonded to:

- \( \mathrm{N} \) → e.g., \( \mathrm{NH_3} \), amines

- \( \mathrm{O} \) → e.g., \( \mathrm{H_2O} \), alcohols, carboxylic acids

Comparison Table

| Intermolecular Force | Cause | Relative Strength | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| pd–pd | Attraction between permanent dipoles | Medium | \( \mathrm{HCl} \) |

| Hydrogen bonding | \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) + lone pairs | Strongest type of pd–pd | \( \mathrm{H_2O} \), \( \mathrm{NH_3} \) |

Example

Which molecules can form hydrogen bonds: \( \mathrm{CH_3OH} \), \( \mathrm{CH_4} \), \( \mathrm{NH_3} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{CH_3OH} \) has an \( \mathrm{O–H} \) group → hydrogen bonding.

\( \mathrm{NH_3} \) has \( \mathrm{N–H} \) groups → hydrogen bonding.

\( \mathrm{CH_4} \) has no \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) → no hydrogen bonding.

Example

Explain why hydrogen bonding is stronger than ordinary permanent dipole–permanent dipole forces.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

N and O are very electronegative → large partial charges.

Hydrogen is very small → molecules can get close → stronger attraction.

This produces a very strong pd–pd interaction known as a hydrogen bond.

Example

Explain why ethanol forms stronger intermolecular forces than chloromethane.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Ethanol contains an \( \mathrm{O–H} \) group → can form hydrogen bonds.

Chloromethane (\( \mathrm{CH_3Cl} \)) has a permanent dipole but no \( \mathrm{N–H} \) or \( \mathrm{O–H} \) → only pd–pd forces.

Hydrogen bonding is a much stronger form of pd–pd force.

Therefore ethanol has stronger intermolecular forces and a higher boiling point.

Strength of Bonding vs Intermolecular Forces

The bonds holding atoms together within a substance (ionic, covalent, metallic) are generally much stronger than the forces that act between molecules (intermolecular forces such as London forces, pd–pd forces and hydrogen bonding).

Statement

In general, ionic, covalent and metallic bonding are much stronger than all types of intermolecular forces.

Explanation

- Ionic bonds involve strong electrostatic attraction between oppositely charged ions.

- Covalent bonds involve shared electron pairs between atoms.

- Metallic bonds involve attraction between positive metal ions and delocalised electrons.

- Intermolecular forces act between molecules, not within them → therefore much weaker.

- Breaking bonds (ionic/covalent/metallic) requires much more energy than overcoming intermolecular forces.

Comparison Table

| Type of Interaction | Examples | Relative Strength | Energy Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic bonding | \( \mathrm{NaCl} \), \( \mathrm{MgO} \) | Very strong | High (break lattice) |

| Covalent bonding | \( \mathrm{H_2} \), \( \mathrm{CH_4} \) | Strong | High (break bond) |

| Metallic bonding | Fe, Cu, Al | Strong | High |

| Intermolecular forces | London, pd–pd, hydrogen bonding | Much weaker | Low–medium |

Example

Which is stronger: the covalent O–H bond within a water molecule or the hydrogen bonds between water molecules?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The covalent O–H bond is much stronger.

Hydrogen bonds are intermolecular forces and are weaker.

Example

Explain why sodium chloride has a much higher melting point than iodine molecules.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{NaCl} \) has strong ionic bonds throughout its giant lattice → requires large energy to break.

Iodine has simple molecules held together only by London forces → much weaker.

Example

Explain why metals such as copper have much higher melting points than substances like ethanol.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Copper contains a giant metallic structure with strong attraction between positive metal ions and delocalised electrons → requires very large amounts of energy to break.

Ethanol molecules are held together by hydrogen bonding, which is strong for an intermolecular force but far weaker than metallic bonding.

Therefore copper has a much higher melting point.