CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 4.1 The gaseous state: ideal and real gases and $p V=n R T$ Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 4.1 The gaseous state: ideal and real gases and $p V=n R T$ Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 4.1 The gaseous state: ideal and real gases and $p V=n R T$ Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

- explain the origin of pressure in a gas in terms of collisions between gas molecules and the wall of the container

- understand that ideal gases have zero particle volume and no intermolecular forces of attraction

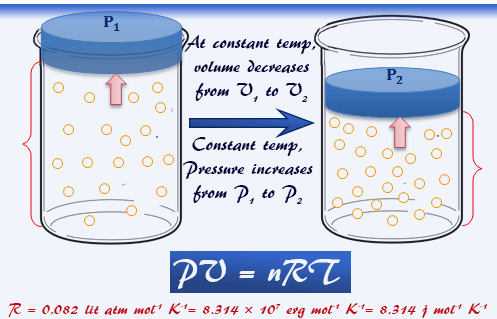

- state and use the ideal gas equation pV = nRT in calculations, including in the determination of Mr

Origin of Gas Pressure — Collisions of Molecules with Container Walls

Gas molecules are in continuous, rapid, random motion. They collide with each other and with the walls of the container. These collisions with the container walls create a force, and the pressure is the force per unit area.

Why Gas Pressure Exists

- Gas molecules move randomly at high speeds.

- When a molecule collides with a wall, it exerts a force on that wall.

- Millions of such collisions occur every second.

- The total force from all these collisions over an area produces the gas pressure.

Gas pressure \( \displaystyle = \frac{\text{force due to molecular collisions}}{\text{area of container wall}} \)

Key Ideas (Kinetic Theory)

![]()

- Molecules have momentum; collisions with walls change their momentum.

- A change in momentum means a force has acted (Newton’s laws).

- The sum of these forces produces the pressure.

- Higher temperature → faster molecules → more frequent, harder collisions → higher pressure.

- Smaller volume → molecules hit walls more often → higher pressure.

Example

Why does a gas exert pressure on its container?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Gas molecules collide with the container walls.

Each collision exerts a small force; many collisions together create pressure.

Example

Explain why the pressure of a fixed mass of gas increases when heated at constant volume.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Heating increases molecular kinetic energy → molecules move faster.

They collide more frequently and with greater force.

Greater force per unit area → higher pressure.

Example

Use momentum ideas to explain how gas pressure arises.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Molecules hitting the walls undergo a change in momentum.

By Newton’s second law, this change produces a force.

The wall experiences an equal and opposite force (Newton’s third law).

Many such forces acting over the wall’s surface → gas pressure.

Ideal Gas Assumptions — Zero Particle Volume and No Intermolecular Forces

An ideal gas is a theoretical model used to simplify the behaviour of gases. The model is based on two key assumptions: gas particles have no volume of their own and there are no forces of attraction between them.

Key Assumption 1: Gas Particles Have Zero Volume

- Ideal gas particles are treated as point masses.

- This means each particle has zero volume and takes up no space.

- Therefore, the total volume of the gas is entirely the volume of the container.

- Real gases have particle volume, but this assumption works well at low pressure.

In the ideal gas model: the particle volume \( \mathrm{\approx 0} \).

Key Assumption 2: No Intermolecular Forces

- Ideal gas particles do not attract or repel each other.

- Collisions between gas particles are perfectly elastic.

- Particles move in straight lines between collisions.

- In reality, gases do have weak intermolecular forces (van der Waals’ forces), but these become negligible at high temperature and low pressure.

In the ideal gas model: intermolecular attraction \( \mathrm{= 0} \).

Why These Assumptions Matter

- With no attractions and no volume, ideal gases obey the ideal gas equation perfectly:

\( pV = nRT \)

- Real gases often deviate from this, especially at high pressure or low temperature.

Example

State one assumption made about intermolecular forces in an ideal gas.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

An ideal gas has no intermolecular forces between particles.

Example

Explain why ideal gas particles are assumed to have zero volume.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Treating particles as point masses simplifies calculations and allows all the measured volume to be considered the container’s volume. Real gas particles do have volume, but it is small compared with the container volume at low pressure.

Example

Explain why real gases deviate from ideal behaviour at high pressure.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

At high pressure, gas particles are forced closer together.

Their own volume becomes significant compared with the container volume → violating the ideal assumption that particle volume is zero.

Also, intermolecular forces become stronger at short distances → violating the assumption of no forces.

Therefore, real gases do not behave ideally under high pressure.

The Ideal Gas Equation — \( pV = nRT \)

The ideal gas equation relates pressure, volume, temperature and moles for a gas behaving ideally. It can also be used to calculate the relative molecular mass \( \mathrm{M_r} \).

The Ideal Gas Equation

\( pV = nRT \)

- \( p \) = pressure in \( \mathrm{Pa} \)

- \( V \) = volume in \( \mathrm{m^3} \)

- \( n \) = moles of gas

- \( R \) = gas constant = \( 8.314\ \mathrm{J\ mol^{-1}\ K^{-1}} \)

- \( T \) = temperature in \( \mathrm{K} \)

Convert units before substituting:

- \( \mathrm{cm^3 \to m^3} \): divide by \( 10^6 \)

- \( \mathrm{dm^3 \to m^3} \): divide by \( 1000 \)

- °C → K: add \( 273 \)

Using the Equation to Find \( n \)

\( n = \dfrac{pV}{RT} \)

Using the Equation to Find \( \mathrm{M_r} \)

If mass \( m \) is known: \( n = \dfrac{m}{M_r} \) → substitute into \( pV = nRT \)

Therefore: \( M_r = \dfrac{mRT}{pV} \)

Example

A gas has a pressure of \( 100\,000\ \mathrm{Pa} \), volume \( 0.010\ \mathrm{m^3} \), and temperature \( 300\ \mathrm{K} \). Calculate the number of moles.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( n = \dfrac{pV}{RT} \)

\( n = \dfrac{100\,000 \times 0.010}{8.314 \times 300} \)

\( n = 0.401\ \mathrm{mol} \)

Example

Calculate the volume occupied by \( 0.50\ \mathrm{mol} \) of gas at \( 25^\circ\mathrm{C} \) and \( 1.00\times10^5\ \mathrm{Pa} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Convert temperature: \( 25^\circ\mathrm{C} = 298\ \mathrm{K} \)

\( pV = nRT \)

\( V = \dfrac{nRT}{p} \)

\( V = \dfrac{0.50 \times 8.314 \times 298}{1.00\times10^5} \)

\( V = 0.0124\ \mathrm{m^3} \) (or \( 12.4\ \mathrm{dm^3} \))

Example

A \( 2.00\ \mathrm{g} \) sample of a gaseous compound occupies \( 750\ \mathrm{cm^3} \) at \( 20^\circ\mathrm{C} \) and \( 101\,000\ \mathrm{Pa} \). Calculate its \( \mathrm{M_r} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Convert volume: \( 750\ \mathrm{cm^3} = 7.50\times10^{-4}\ \mathrm{m^3} \)

Convert temperature: \( 20^\circ\mathrm{C} = 293\ \mathrm{K} \)

Use: \( M_r = \dfrac{mRT}{pV} \)

\( M_r = \dfrac{2.00 \times 8.314 \times 293}{101\,000 \times 7.50\times10^{-4}} \)

\( M_r = 64.4 \)

The relative molecular mass of the gas is \( \mathrm{M_r = 64.4} \).