CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 7.1 Chemical equilibria: reversible reactions, dynamic equilibrium Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 7.1 Chemical equilibria: reversible reactions, dynamic equilibrium Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Chemistry 7.1 Chemical equilibria: reversible reactions, dynamic equilibrium Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Chemistry latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

(a) understand what is meant by a reversible reaction

(b) understand what is meant by dynamic equilibrium in terms of the rate of forward and reverse reactions being equal and the concentration of reactants and products remaining constant

(c) understand the need for a closed system in order to establish dynamic equilibriumdefine Le Chatelier’s principle as:

if a change is made to a system at dynamic equilibrium, the position of equilibrium moves to minimise this changeuse Le Chatelier’s principle to deduce qualitatively the effects of changes in temperature, concentration, pressure or presence of a catalyst on a system at equilibrium

deduce expressions for equilibrium constants in terms of concentrations, Kc

use the terms mole fraction and partial pressure

deduce expressions for equilibrium constants in terms of partial pressures, Kp

(use of the relationship between Kp and Kc is not required)use the Kc and Kp expressions to carry out calculations

(such calculations will not require solving quadratic equations)calculate the quantities present at equilibrium, given appropriate data

state whether changes in temperature, concentration, pressure or presence of a catalyst affect the value of the equilibrium constant

describe and explain the conditions used in the Haber process and the Contact process, showing the importance of dynamic equilibrium and Le Chatelier’s principle in industry

Reversible Reactions and Dynamic Equilibrium

Many chemical reactions do not go to completion. Instead, the products can react to reform the original reactants. Such systems can reach a state known as dynamic equilibrium.

(a) Reversible Reactions

A reversible reaction is a reaction in which the products can react together to reform the original reactants.

![]()

Reversible reactions are represented using a double arrow:

\( \mathrm{A + B \rightleftharpoons C + D} \)

- The forward reaction converts reactants into products.

- The reverse reaction converts products back into reactants.

- Both reactions occur simultaneously.

Example: \( \mathrm{N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3} \)

(b) Dynamic Equilibrium

Dynamic equilibrium is reached in a reversible reaction when:

- the rate of the forward reaction equals the rate of the reverse reaction

- the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant

Although concentrations remain constant, reactions continue to occur at the particle level — this is why the equilibrium is described as dynamic, not static.

At equilibrium: \( \text{rate of forward reaction} = \text{rate of reverse reaction} \)

(c) Closed System and Dynamic Equilibrium

A closed system is required to establish dynamic equilibrium.

![]()

- No reactants or products can enter or leave the system.

- If products escape, the reverse reaction cannot occur.

- Without a closed system, equilibrium cannot be achieved.

Example: If ammonia gas is allowed to escape from the Haber process, the reverse reaction cannot take place and equilibrium is not established.

Example

State what is meant by a reversible reaction.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A reversible reaction is one in which the products can react to reform the original reactants.

Example

Explain what is meant by dynamic equilibrium.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Dynamic equilibrium is a state where the forward and reverse reactions occur at equal rates, so the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant.

Example

Explain why a closed system is required for dynamic equilibrium to be established.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

If the system is not closed, reactants or products can escape. This prevents the reverse reaction from occurring at the same rate as the forward reaction, so dynamic equilibrium cannot be reached.

Le Chatelier’s Principle

Le Chatelier’s principle describes how a system at dynamic equilibrium responds to changes in conditions.

Definition of Le Chatelier’s Principle

Le Chatelier’s principle states that:

If a change is made to a system at dynamic equilibrium, the position of equilibrium moves to minimise that change.

The system responds in a way that counteracts the applied change and attempts to restore equilibrium.

Meaning of “Position of Equilibrium”

- The position of equilibrium refers to the relative amounts of reactants and products present.

- A shift to the right favours products.

- A shift to the left favours reactants.

- The equilibrium constant does not change unless temperature changes.

Example

State Le Chatelier’s principle.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

If a change is made to a system at dynamic equilibrium, the equilibrium moves to oppose the change.

Example

Consider the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3} \)

Explain what happens to the equilibrium position if more hydrogen is added.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Adding hydrogen increases the concentration of a reactant.

The equilibrium moves to the right to reduce this change by using up hydrogen, forming more ammonia.

Example

Explain why removing a product from a system at equilibrium causes the forward reaction to be favoured.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Removing a product decreases its concentration.

The equilibrium shifts in the forward direction to replace the removed product and minimise the change, according to Le Chatelier’s principle.

Using Le Chatelier’s Principle to Predict Changes in Equilibrium

Le Chatelier’s principle can be used to predict qualitatively how a system at dynamic equilibrium responds to changes in temperature, concentration, pressure, or the presence of a catalyst.

![]()

Effect of Temperature

Temperature changes affect equilibrium depending on whether the forward reaction is exothermic or endothermic.

- Increasing temperature favours the endothermic direction.

- Decreasing temperature favours the exothermic direction.

- The system shifts to oppose the temperature change.

Example: \( \mathrm{N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3} \quad \Delta H < 0 \)

Increasing temperature shifts equilibrium to the left (endothermic direction), reducing ammonia yield.

Effect of Concentration

Changing the concentration of reactants or products causes the equilibrium to shift to minimise that change.

- Increasing reactant concentration shifts equilibrium towards products.

- Increasing product concentration shifts equilibrium towards reactants.

- Removing a substance causes equilibrium to shift to replace it.

Effect of Pressure (Gaseous Systems)

Pressure changes only affect equilibria involving gases where the total number of gas molecules differs between sides.

- Increasing pressure favours the side with fewer moles of gas.

- Decreasing pressure favours the side with more moles of gas.

- If the number of gas moles is equal on both sides, pressure has no effect.

Example: \( \mathrm{N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3} \) 4 moles of gas → 2 moles of gas

Effect of a Catalyst

A catalyst increases the rate of both the forward and reverse reactions equally.

- Does not change the position of equilibrium.

- Does not change equilibrium concentrations.

- Allows equilibrium to be reached faster.

Example

State the effect of adding a catalyst to a system at equilibrium.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A catalyst does not change the position of equilibrium but allows it to be reached more quickly.

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{2SO_2 + O_2 \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3} \quad \Delta H < 0 \)

Predict the effect of increasing temperature.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The forward reaction is exothermic.

Increasing temperature favours the endothermic direction, so equilibrium shifts to the left, reducing the yield of \( \mathrm{SO_3} \).

Example

Consider the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{CO + H_2O \rightleftharpoons CO_2 + H_2} \quad \Delta H < 0 \)

Explain the effect of:

(i) increasing pressure

(ii) removing \( \mathrm{CO_2} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

(i) Pressure:

There are equal moles of gas on both sides (2 → 2), so changing pressure has no effect on equilibrium position.

(ii) Removing \( \mathrm{CO_2} \):

This decreases the product concentration.

The equilibrium shifts to the right to produce more \( \mathrm{CO_2} \), minimising the change.

Equilibrium Constants in Terms of Concentrations, \( K_c \)

For reactions at equilibrium, the equilibrium constant \( K_c \) provides a quantitative measure of the position of equilibrium. It is written using the equilibrium concentrations of reactants and products.

Definition of \( K_c \)

The equilibrium constant \( K_c \) is defined as:

the ratio of the product of equilibrium concentrations of products to reactants, each raised to the power of their stoichiometric coefficients.

General Expression for \( K_c \)![]()

For a general reversible reaction:

\( \mathrm{aA + bB \rightleftharpoons cC + dD} \)

The equilibrium constant expression is:

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{C}]^c[\mathrm{D}]^d}{[\mathrm{A}]^a[\mathrm{B}]^b} \)

- Square brackets denote equilibrium concentration in \( \mathrm{mol\ dm^{-3}} \).

- Only species in solution or gas phase are included.

- Pure solids and pure liquids are omitted.

Important Points About \( K_c \)

- The value of \( K_c \) is constant at a given temperature.

- A large \( K_c \) indicates products are favoured.

- A small \( K_c \) indicates reactants are favoured.

- Changing concentrations does not change \( K_c \); it only shifts the equilibrium position.

Example

Write the \( K_c \) expression for:

\( \mathrm{H_2 + I_2 \rightleftharpoons 2HI} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{HI}]^2}{[\mathrm{H_2}][\mathrm{I_2}]} \)

Example

Deduce the expression for \( K_c \) for the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{2SO_2 + O_2 \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The coefficients become the powers in the expression.

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{[\mathrm{SO_2}]^2[\mathrm{O_2}]} \)

Example

Write the \( K_c \) expression for the reaction:

\( \mathrm{CaCO_3(s) \rightleftharpoons CaO(s) + CO_2(g)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Pure solids are omitted from the expression.

\( K_c = [\mathrm{CO_2}] \)

Mole Fraction and Partial Pressure

In gaseous mixtures, the composition of the mixture and the contribution of each gas to the total pressure can be described using the terms mole fraction and partial pressure. These ideas are essential when dealing with equilibria and gas-phase reactions.

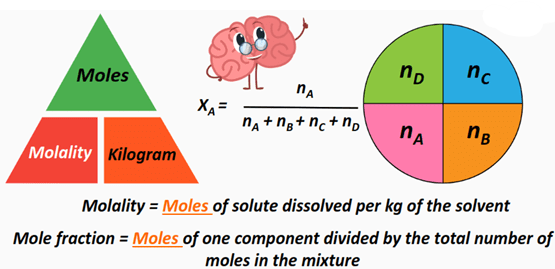

Mole Fraction

The mole fraction of a component in a mixture is the fraction of the total moles that is made up by that component.

\( \text{Mole fraction of A} = \dfrac{n_A}{n_\text{total}} \)

- \( n_A \) = moles of component A

- \( n_\text{total} \) = total moles of all components

- Mole fraction has no units.

- The sum of all mole fractions in a mixture equals 1.

Partial Pressure

The partial pressure of a gas is the pressure that the gas would exert if it occupied the container alone at the same temperature.

\( p_A = \chi_A \times p_\text{total} \)

- \( p_A \) = partial pressure of gas A

- \( \chi_A \) = mole fraction of gas A

- \( p_\text{total} \) = total pressure of the gas mixture

This relationship follows Dalton’s law of partial pressures.

Relationship Between Mole Fraction and Partial Pressure

- A gas with a larger mole fraction contributes a larger partial pressure.

- If the mole fraction doubles, the partial pressure also doubles (at constant total pressure).

- Partial pressures can be added to give the total pressure.

Example

A mixture contains 2 mol of nitrogen and 3 mol of hydrogen. Calculate the mole fraction of nitrogen.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Total moles = \( 2 + 3 = 5 \)

Mole fraction of nitrogen:

\( \chi_{\mathrm{N_2}} = \dfrac{2}{5} = 0.40 \)

Example

A gas mixture has a total pressure of \( 100\ \mathrm{kPa} \). The mole fraction of oxygen is 0.21. Calculate the partial pressure of oxygen.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use \( p_A = \chi_A \times p_\text{total} \)

\( p_{\mathrm{O_2}} = 0.21 \times 100 = 21\ \mathrm{kPa} \)

Example

A mixture contains 1.0 mol of \( \mathrm{CO} \), 2.0 mol of \( \mathrm{CO_2} \), and 1.0 mol of \( \mathrm{N_2} \). The total pressure is \( 200\ \mathrm{kPa} \).

(i) Calculate the mole fraction of \( \mathrm{CO_2} \). (ii) Calculate the partial pressure of \( \mathrm{CO_2} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

(i) Mole fraction

Total moles = \( 1.0 + 2.0 + 1.0 = 4.0 \)

\( \chi_{\mathrm{CO_2}} = \dfrac{2.0}{4.0} = 0.50 \)

(ii) Partial pressure

\( p_{\mathrm{CO_2}} = 0.50 \times 200 = 100\ \mathrm{kPa} \)

Equilibrium Constants in Terms of Partial Pressures, \( K_p \)

For reactions involving gases, the position of equilibrium can be described using the equilibrium constant \( K_p \), which is written in terms of the partial pressures of gaseous reactants and products.

Definition of \( K_p \)

The equilibrium constant \( K_p \) is defined as:

the ratio of the product of equilibrium partial pressures of gaseous products to reactants, each raised to the power of their stoichiometric coefficients.

General Expression for \( K_p \)

For a general gas-phase reaction:

\( \mathrm{aA(g) + bB(g) \rightleftharpoons cC(g) + dD(g)} \)

The equilibrium constant expression is:

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{C}})^c (p_{\mathrm{D}})^d}{(p_{\mathrm{A}})^a (p_{\mathrm{B}})^b} \)

- \( p \) represents the equilibrium partial pressure (usually in \( \mathrm{kPa} \) or \( \mathrm{Pa} \)).

- Only gaseous species are included in the expression.

- Pure solids and liquids are omitted.

Important Features of \( K_p \)

- The value of \( K_p \) depends only on temperature.

- A large \( K_p \) indicates products are favoured.

- A small \( K_p \) indicates reactants are favoured.

- Changing pressure shifts equilibrium position but does not change \( K_p \) (unless temperature changes).

Example

Write the expression for \( K_p \) for the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{H_2(g) + I_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2HI(g)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{HI}})^2}{(p_{\mathrm{H_2}})(p_{\mathrm{I_2}})} \)

Example

Deduce the expression for \( K_p \) for:

\( \mathrm{N_2(g) + 3H_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3(g)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2}{(p_{\mathrm{N_2}})(p_{\mathrm{H_2}})^3} \)

Example

Write the \( K_p \) expression for the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{CaCO_3(s) \rightleftharpoons CaO(s) + CO_2(g)} \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Solids are omitted from the expression.

\( K_p = p_{\mathrm{CO_2}} \)

Using \( K_c \) and \( K_p \) Expressions to Carry Out Calculations

The equilibrium constants \( K_c \) and \( K_p \) can be used to calculate unknown equilibrium concentrations or partial pressures when all other values are known. In this syllabus, calculations will not require the solving of quadratic equations.

General Approach to Equilibrium Calculations

- Write the balanced chemical equation.

- Write the correct \( K_c \) or \( K_p \) expression.

- Substitute known equilibrium concentrations or partial pressures.

- Solve the equation to find the unknown value.

- Check units and significant figures.

Using \( K_c \) for Concentration Calculations

For a general reaction:

\( \mathrm{aA + bB \rightleftharpoons cC + dD} \)

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{C}]^c[\mathrm{D}]^d}{[\mathrm{A}]^a[\mathrm{B}]^b} \)

All concentrations are equilibrium concentrations in \( \mathrm{mol\ dm^{-3}} \).

Using \( K_p \) for Partial Pressure Calculations

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\text{products}})^{\text{coefficients}}}{(p_{\text{reactants}})^{\text{coefficients}}} \)

Partial pressures are usually given in \( \mathrm{kPa} \) or \( \mathrm{Pa} \), but must be consistent.

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{H_2 + I_2 \rightleftharpoons 2HI} \)

At equilibrium, \( [\mathrm{H_2}] = 0.20 \), \( [\mathrm{I_2}] = 0.20 \), \( [\mathrm{HI}] = 0.60 \). Calculate \( K_c \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{HI}]^2}{[\mathrm{H_2}][\mathrm{I_2}]} \)

\( K_c = \dfrac{(0.60)^2}{(0.20)(0.20)} = \dfrac{0.36}{0.04} = 9.0 \)

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{2SO_2 + O_2 \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3} \)

\( K_c = 25 \). At equilibrium, \( [\mathrm{SO_2}] = 0.20 \) and \( [\mathrm{O_2}] = 0.40 \). Calculate \( [\mathrm{SO_3}] \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{[\mathrm{SO_2}]^2[\mathrm{O_2}]} \)

Substitute values:

\( 25 = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{(0.20)^2(0.40)} \)

\( 25 = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{0.016} \)

\( [\mathrm{SO_3}]^2 = 25 \times 0.016 = 0.40 \)

\( [\mathrm{SO_3}] = \sqrt{0.40} = 0.63\ \mathrm{mol\ dm^{-3}} \)

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{N_2(g) + 3H_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3(g)} \)

\( K_p = 4.0 \times 10^{-2} \)

At equilibrium:

\( p_{\mathrm{N_2}} = 200\ \mathrm{kPa} \), \( p_{\mathrm{H_2}} = 300\ \mathrm{kPa} \). Calculate \( p_{\mathrm{NH_3}} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2}{(p_{\mathrm{N_2}})(p_{\mathrm{H_2}})^3} \)

Substitute values:

\( 4.0 \times 10^{-2} = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2}{(200)(300)^3} \)

\( (p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2 = 4.0 \times 10^{-2} \times 200 \times 27\,000\,000 \)

\( (p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2 = 2.16 \times 10^{8} \)

\( p_{\mathrm{NH_3}} = 1.47 \times 10^{4}\ \mathrm{kPa} \)

Calculating Quantities Present at Equilibrium

The quantities present at equilibrium can be calculated using equilibrium constants (\( K_c \) or \( K_p \)) together with given initial amounts or concentrations. These calculations use the idea that reactants and products change until equilibrium is reached.

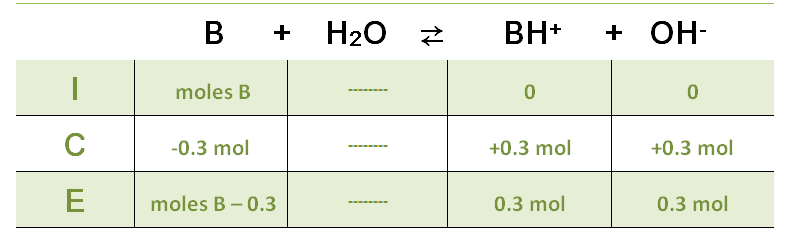

General Method (ICE Approach)

- I – Initial: write the initial concentrations or partial pressures.

- C – Change: show how amounts change as equilibrium is approached.

- E – Equilibrium: write expressions for equilibrium values.

- Substitute equilibrium values into the \( K_c \) or \( K_p \) expression.

- Solve to find the required equilibrium quantity.

Only simple algebra is required; quadratic equations are not needed.

Example Reaction

\( \mathrm{A + B \rightleftharpoons C} \)

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{C}]}{[\mathrm{A}][\mathrm{B}]} \)

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{H_2 + I_2 \rightleftharpoons 2HI} \)

\( K_c = 16 \)

At equilibrium, \( [\mathrm{H_2}] = 0.20 \) and \( [\mathrm{I_2}] = 0.20 \).

Calculate \( [\mathrm{HI}] \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{HI}]^2}{[\mathrm{H_2}][\mathrm{I_2}]} \)

\( 16 = \dfrac{[\mathrm{HI}]^2}{(0.20)(0.20)} \)

\( [\mathrm{HI}]^2 = 16 \times 0.04 = 0.64 \)

\( [\mathrm{HI}] = 0.80\ \mathrm{mol\ dm^{-3}} \)

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{2SO_2 + O_2 \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3} \)

\( K_c = 50 \)

At equilibrium:

\( [\mathrm{SO_2}] = 0.10 \), \( [\mathrm{O_2}] = 0.20 \)

Calculate \( [\mathrm{SO_3}] \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_c = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{[\mathrm{SO_2}]^2[\mathrm{O_2}]} \)

\( 50 = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{(0.10)^2(0.20)} \)

\( 50 = \dfrac{[\mathrm{SO_3}]^2}{0.002} \)

\( [\mathrm{SO_3}]^2 = 0.10 \)

\( [\mathrm{SO_3}] = 0.32\ \mathrm{mol\ dm^{-3}} \)

Example

For the equilibrium:

\( \mathrm{N_2(g) + 3H_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3(g)} \)

\( K_p = 0.040 \)

At equilibrium:

\( p_{\mathrm{N_2}} = 100\ \mathrm{kPa} \), \( p_{\mathrm{H_2}} = 200\ \mathrm{kPa} \)

Calculate \( p_{\mathrm{NH_3}} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( K_p = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2}{(p_{\mathrm{N_2}})(p_{\mathrm{H_2}})^3} \)

\( 0.040 = \dfrac{(p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2}{(100)(200)^3} \)

\( (p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2 = 0.040 \times 100 \times 8.0 \times 10^6 \)

\( (p_{\mathrm{NH_3}})^2 = 3.2 \times 10^7 \)

\( p_{\mathrm{NH_3}} = 5.7 \times 10^3\ \mathrm{kPa} \)

Factors Affecting the Value of the Equilibrium Constant

For a chemical reaction at equilibrium, the value of the equilibrium constant (\( K_c \) or \( K_p \)) depends on specific conditions. It is important to know which factors change the value of the equilibrium constant and which do not.

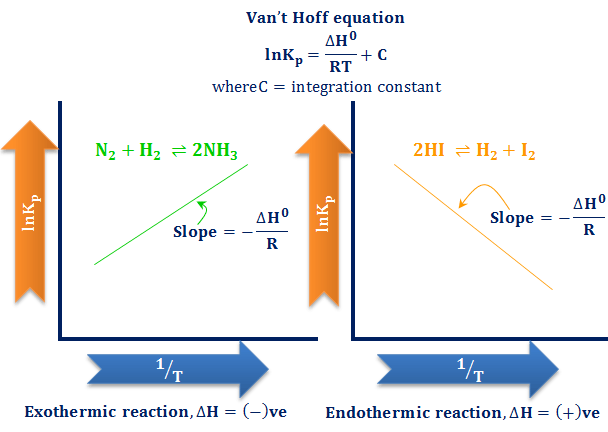

Effect of Temperature

Temperature is the only factor that changes the value of the equilibrium constant.

- For an exothermic reaction (\( \Delta H < 0 \)):

- Increasing temperature decreases \( K \).

- Decreasing temperature increases \( K \).

- For an endothermic reaction (\( \Delta H > 0 \)):

- Increasing temperature increases \( K \).

- Decreasing temperature decreases \( K \).

Reason: changing temperature changes the relative energies of reactants and products, altering the position of equilibrium.

Effect of Concentration

Changing the concentration of reactants or products:

- shifts the position of equilibrium

- does not change the value of \( K_c \)

The system responds to restore equilibrium, but the equilibrium constant remains the same.

Effect of Pressure

Changing pressure (or volume) in a gaseous equilibrium:

- may change the position of equilibrium

- does not change the value of \( K_p \)

Pressure changes affect how equilibrium is reached, not the value of the equilibrium constant.

Effect of a Catalyst

A catalyst:

- does not change the position of equilibrium

- does not change the value of \( K_c \) or \( K_p \)

- increases the rate of both forward and reverse reactions equally

Equilibrium is reached faster, but the final equilibrium composition is unchanged.

| Change | Effect on equilibrium position | Effect on value of \( K \) |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Yes | Yes |

| Concentration | Yes | No |

| Pressure | Yes (gases only) | No |

| Catalyst | No | No |

Example

Which factor always changes the value of the equilibrium constant?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Temperature is the only factor that changes the value of the equilibrium constant.

Example

For an exothermic reaction, explain the effect of increasing temperature on \( K \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Increasing temperature favours the endothermic direction, reducing product formation.

This causes the value of the equilibrium constant to decrease.

Example

Explain why adding a catalyst does not change the value of the equilibrium constant.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A catalyst lowers activation energy for both forward and reverse reactions equally.

This does not change the energies of reactants or products, so the equilibrium constant remains unchanged.

Dynamic Equilibrium and Industrial Chemical Processes

The Haber process and the Contact process are important industrial reactions that operate under conditions chosen using an understanding of dynamic equilibrium and Le Chatelier’s principle. These conditions are a compromise between yield, rate, safety and cost.

The Haber Process (Manufacture of Ammonia)

The Haber process produces ammonia, which is used to make fertilisers.

![]()

\( \mathrm{N_2(g) + 3H_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3(g)} \quad \Delta H < 0 \)

Effect of Conditions

- Temperature:

- The reaction is exothermic.

- Lower temperature favours ammonia formation.

- However, too low a temperature gives a slow reaction.

- A compromise temperature of about 450 °C is used.

- Pressure:

- 4 moles of gas form 2 moles of gas.

- High pressure favours ammonia formation.

- A pressure of about 200 atm is used as a compromise between yield and cost.

- Catalyst:

- An iron catalyst is used.

- It increases the rate of both forward and reverse reactions.

- It does not change the position of equilibrium.

Importance of Equilibrium

Ammonia is continuously removed from the system, shifting the equilibrium to the right and increasing yield.

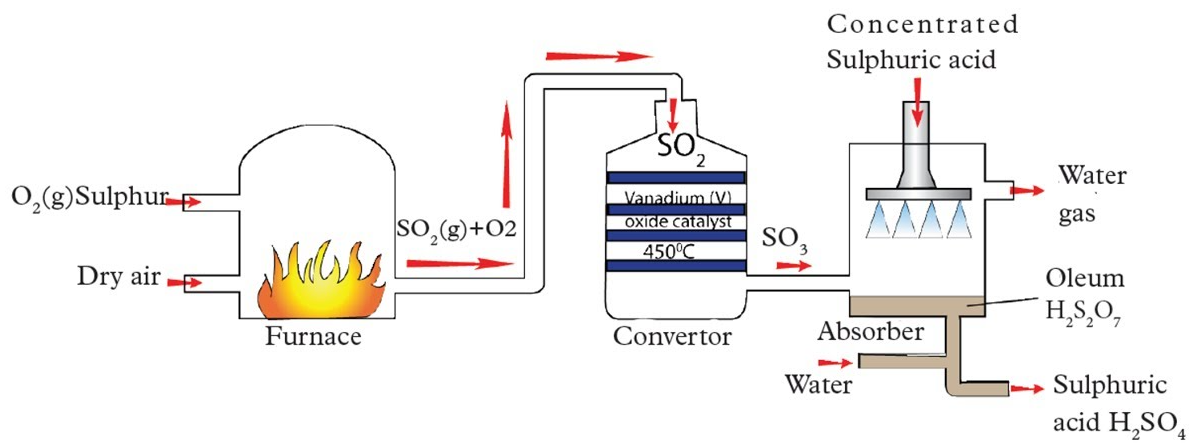

The Contact Process (Manufacture of Sulfuric Acid)

The Contact process produces sulfur trioxide, which is then used to make sulfuric acid.

\( \mathrm{2SO_2(g) + O_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3(g)} \quad \Delta H < 0 \)

Effect of Conditions

- Temperature:

- The reaction is exothermic.

- Low temperature favours sulfur trioxide.

- A compromise temperature of about 450 °C is used to give a reasonable rate.

- Pressure:

- 3 moles of gas form 2 moles of gas.

- High pressure favours products.

- Only a slight pressure (about 1–2 atm) is used because yield is already high.

- Catalyst:

- Vanadium(V) oxide, \( \mathrm{V_2O_5} \), is used as a catalyst.

- It speeds up the reaction but does not alter equilibrium position.

Comparison of the Two Processes

| Feature | Haber Process | Contact Process |

|---|---|---|

| Main product | Ammonia | Sulfuric acid (via SO₃) |

| Reaction type | Exothermic | Exothermic |

| Temperature | ≈ 450 °C | ≈ 450 °C |

| Pressure | ≈ 200 atm | ≈ 1–2 atm |

| Catalyst | Iron | \( \mathrm{V_2O_5} \) |

Example

State one reason why high pressure is used in the Haber process.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

High pressure favours the formation of ammonia because fewer moles of gas are produced.

Example

Explain why a catalyst is used in both the Haber and Contact processes.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

A catalyst increases the rate at which equilibrium is reached, making the process faster without changing the equilibrium yield.

Example

Explain why a moderate temperature is used in the Haber process instead of a very low temperature.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Although low temperature favours ammonia formation, it would make the reaction too slow.

A moderate temperature provides a compromise between a high yield and an acceptable reaction rate.