AP Precalculus -4.8 Vectors- Study Notes - Effective Fall 2023

AP Precalculus -4.8 Vectors- Study Notes – Effective Fall 2023

AP Precalculus -4.8 Vectors- Study Notes – AP Precalculus- per latest AP Precalculus Syllabus.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify characteristics of a vector.

Determine sums and products involving vectors.

Determine a unit vector for a given vector.

Determine angle measures between vectors and magnitudes of vectors involved in vector addition.

Key Concepts:

Vectors

Vectors Defined by Two Points

Direction and Magnitude of a Vector

Finding Vector Components Using Trigonometry

Scalar Multiplication of Vectors

Vector Addition in ℝ²

Dot Product of Two Vectors

Unit Vectors

Unit Vectors i and j

Geometric Interpretation of the Dot Product

Law of Sines and Law of Cosines in Vector Addition

Vectors

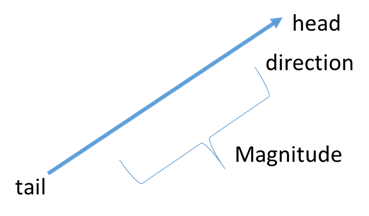

A vector is a directed line segment that represents both a magnitude (length) and a direction.

When a vector is placed in the coordinate plane:

• The point where the vector starts is called the tail.

• The point where the vector ends is called the head.

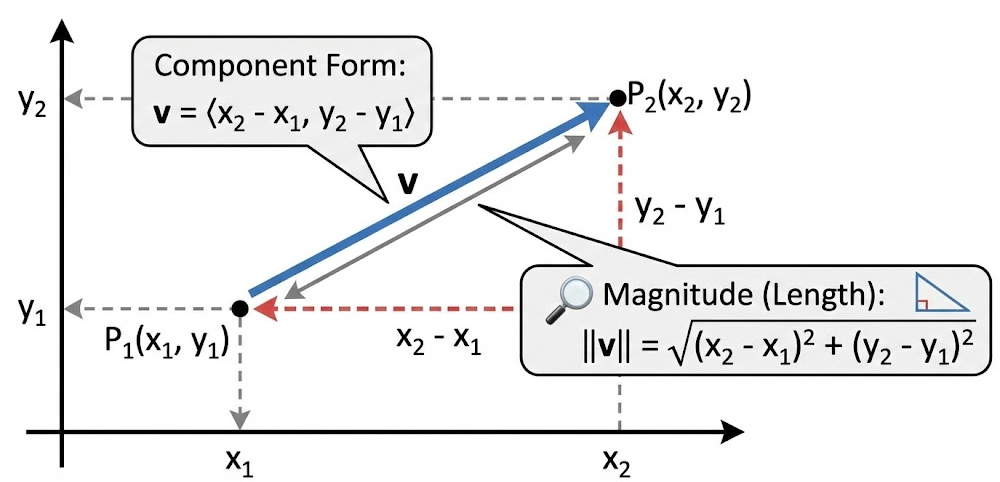

If a vector has tail at point \( (x_1, y_1) \) and head at point \( (x_2, y_2) \), it can be represented in component form as

\( \langle x_2 – x_1,\; y_2 – y_1 \rangle \)

The magnitude of a vector is the length of the directed line segment and is found using the distance formula.

\( \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert = \sqrt{(x_2 – x_1)^2 + (y_2 – y_1)^2} \)

The magnitude measures how long the vector is, independent of its direction.

Example:

A vector has tail at \( (1, 2) \) and head at \( (5, 5) \). Find the vector in component form and its magnitude.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Component form

\( \langle 5 – 1,\; 5 – 2 \rangle = \langle 4,\; 3 \rangle \)

Magnitude

\( \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert = \sqrt{4^2 + 3^2} = \sqrt{16 + 9} = 5 \)

Conclusion: The vector is \( \langle 4, 3 \rangle \) with magnitude 5.

Example:

Find the magnitude of the vector \( \mathbf{v} = \langle -6, 8 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Use the magnitude formula:

\( \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert = \sqrt{(-6)^2 + 8^2} = \sqrt{36 + 64} = \sqrt{100} = 10 \)

Conclusion: The length of the vector is 10 units.

Vectors Defined by Two Points

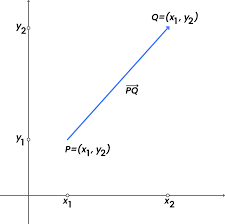

A vector can be represented in the coordinate plane by a directed line segment from one point to another.

Let the vector start at point

\( P = (x_1, y_1) \)

and end at point

\( Q = (x_2, y_2) \).

The vector from \( P\) to \( Q \), written as \( \overrightarrow{PQ} \), has components determined by the change in the coordinates:

\( a = x_2 – x_1 \), \( b = y_2 – y_1 \)

The vector is expressed in component form as

\( \langle a, b \rangle = \langle x_2 – x_1,\; y_2 – y_1 \rangle \).

This form describes the horizontal and vertical displacement needed to move from \( P\) to \( Q \).

A zero vector is the special case where

\( P= Q \),

which gives the vector

\( \langle 0, 0 \rangle \).

The zero vector has no direction and a magnitude of zero.

Example:

Find the vector from \( P_1 = (2, -1) \) to \( P_2 = (6, 4) \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Compute the component changes:

\( a = 6 – 2 = 4 \)

\( b = 4 – (-1) = 5 \)

So the vector is

\( \langle 4, 5 \rangle \).

Conclusion: The vector from \( P_1 \) to \( P_2 \) is \( \langle 4, 5 \rangle \).

Example:

Identify the vector and explain its meaning when \( P_1 = (3, 2) \) and \( P_2 = (3, 2) \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Compute the components:

\( a = 3 – 3 = 0 \), \( b = 2 – 2 = 0 \)

The vector is

\( \langle 0, 0 \rangle \).

Conclusion: Since the starting and ending points are the same, the vector is the zero vector, representing no movement.

Direction and Magnitude of a Vector

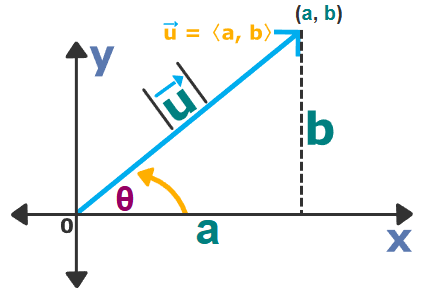

A vector written in component form as \( \langle a, b \rangle \) represents a directed line segment in the plane.

The direction of the vector \( \langle a, b \rangle \) is the same as the direction of the line segment drawn from the origin \( (0,0) \) to the point \( (a, b) \).

This means that all vectors with the same components \( \langle a, b \rangle \) are parallel and point in the same direction, regardless of where they are placed in the plane.

The magnitude (or length) of the vector measures how long the vector is and is found using the Pythagorean Theorem.

\( \lVert \langle a, b \rangle \rVert = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \)

The magnitude depends only on the components of the vector and is always a nonnegative value.

Example:

Find the magnitude and describe the direction of the vector \( \langle 6, 8 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Magnitude

\( \lVert \langle 6, 8 \rangle \rVert = \sqrt{6^2 + 8^2} = \sqrt{36 + 64} = \sqrt{100} = 10 \)

Direction

The vector points in the same direction as the line from the origin to the point \( (6, 8) \), which lies in the first quadrant.

Conclusion: The vector has magnitude 10 and points up and to the right.

Example:

Compare the vectors \( \langle 2, -3 \rangle \) and \( \langle 4, -6 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Both vectors lie along the line from the origin in the direction of \( (2, -3) \).

Since \( \langle 4, -6 \rangle = 2\langle 2, -3 \rangle \), the vectors have the same direction.

Magnitudes:

\( \lVert \langle 2, -3 \rangle \rVert = \sqrt{13} \), \( \lVert \langle 4, -6 \rangle \rVert = \sqrt{52} = 2\sqrt{13} \)

Conclusion: The vectors are parallel and point in the same direction, but \( \langle 4, -6 \rangle \) is twice as long.

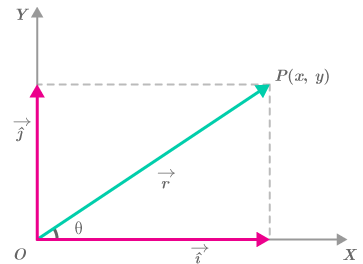

Finding Vector Components Using Trigonometry

A vector represented geometrically in the plane can be analyzed by breaking it into its horizontal and vertical components.

Suppose a vector has magnitude \( r \) and makes an angle \( \theta \) with the positive \( x \)-axis, measured in standard position.

Using right-triangle trigonometry, the components of the vector are given by

\( x = r\cos \theta \)

\( y = r\sin \theta \)

Therefore, the vector can be written in component form as

\( \langle r\cos \theta,\; r\sin \theta \rangle \)

The signs of the components depend on the quadrant in which the vector lies, since \( \cos \theta \) and \( \sin \theta \) change sign by quadrant.

Example:

A vector has magnitude 10 and makes an angle of \( 30^\circ \) with the positive \( x \)-axis. Find its components.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Use the component formulas:

\( x = 10\cos 30^\circ = 10\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = 5\sqrt{3} \)

\( y = 10\sin 30^\circ = 10\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right) = 5 \)

So the vector is

\( \langle 5\sqrt{3},\; 5 \rangle \)

Conclusion: The vector points up and to the right with the given components.

Example:

A vector has magnitude 8 and makes an angle of \( 210^\circ \) with the positive \( x \)-axis. Find its component form.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Since \( 210^\circ \) lies in the third quadrant, both components will be negative.

\( x = 8\cos 210^\circ = 8\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = -4\sqrt{3} \)

\( y = 8\sin 210^\circ = 8\left(-\dfrac{1}{2}\right) = -4 \)

Thus, the vector is

\( \langle -4\sqrt{3},\; -4 \rangle \)

Conclusion: The vector points down and to the left, consistent with its angle.

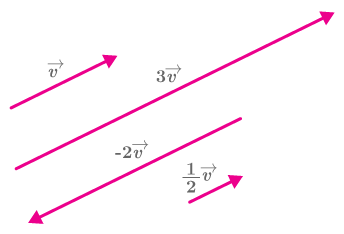

Scalar Multiplication of Vectors

The multiplication of a constant, also called a scalar, and a vector produces a new vector.

If a vector is written in component form as

\( \mathbf{v} = \langle a, b \rangle \),

and \( c \) is a real number, then the scalar multiple of the vector is

\( c\mathbf{v} = \langle ca,\; cb \rangle \).

Each component of the original vector is multiplied by the constant \( c \).

The resulting vector is parallel to the original vector.

• If \( c > 0 \), the new vector points in the same direction as the original.

• If \( c < 0 \), the new vector points in the opposite direction.

The magnitude of the new vector is

\( \lVert c\mathbf{v} \rVert = |c|\lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert \).

Thus, scalar multiplication stretches or shrinks a vector without changing its direction, unless the scalar is negative.

Example:

Let \( \mathbf{v} = \langle 3, -2 \rangle \). Find \( 4\mathbf{v} \) and describe how it compares to \( \mathbf{v} \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Multiply each component by 4:

\( 4\mathbf{v} = \langle 12, -8 \rangle \)

Since \( 4 > 0 \), the new vector points in the same direction as \( \mathbf{v} \).

Its magnitude is 4 times as large.

Conclusion: \( 4\mathbf{v} \) is parallel to \( \mathbf{v} \) and four times as long.

Example:

Let \( \mathbf{u} = \langle 1, 5 \rangle \). Find \( -2\mathbf{u} \) and describe its direction.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Multiply each component by \( -2 \):

\( -2\mathbf{u} = \langle -2, -10 \rangle \)

Because the scalar is negative, the vector points in the opposite direction of \( \mathbf{u} \).

Conclusion: \( -2\mathbf{u} \) is parallel to \( \mathbf{u} \) but reversed in direction and twice as long.

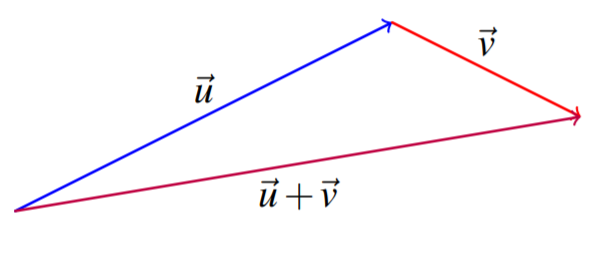

Vector Addition in ℝ²

The sum of two vectors in \( \mathbb{R}^2 \) is a new vector formed by adding the corresponding components of the original vectors.

If

\( \mathbf{u} = \langle a, b \rangle \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{v} = \langle c, d \rangle \),

then their sum is

\( \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v} = \langle a + c,\; b + d \rangle \).

This operation combines the horizontal components and the vertical components separately.

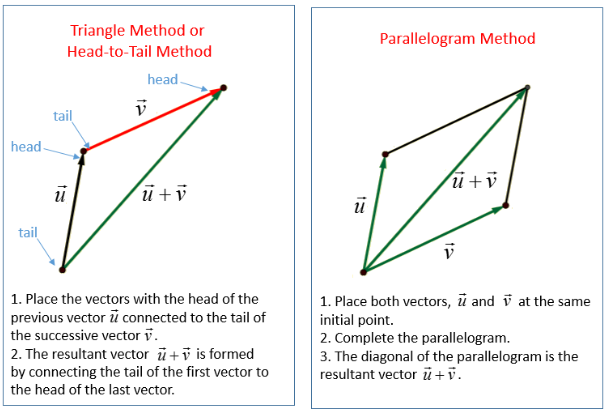

Geometric interpretation

Vector addition can be visualized using the head-to-tail method:

• Place the tail of the second vector at the head of the first vector.

• The sum vector starts at the tail of the first vector and ends at the head of the second vector.

The resulting vector represents the combined displacement of moving along the first vector and then along the second vector.

Example:

Let \( \mathbf{u} = \langle 3, 1 \rangle \) and \( \mathbf{v} = \langle -2, 4 \rangle \). Find \( \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v} \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Add the corresponding components:

\( \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v} = \langle 3 + (-2),\; 1 + 4 \rangle = \langle 1,\; 5 \rangle \)

Conclusion: The sum of the two vectors is \( \langle 1, 5 \rangle \).

Example:

A particle moves 4 units to the right and 2 units up, then moves 1 unit left and 5 units up. Represent this motion using vectors and find the total displacement.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

The first motion is represented by

\( \mathbf{u} = \langle 4, 2 \rangle \)

The second motion is represented by

\( \mathbf{v} = \langle -1, 5 \rangle \)

Add the vectors:

\( \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v} = \langle 4 + (-1),\; 2 + 5 \rangle = \langle 3,\; 7 \rangle \)

Conclusion: The total displacement is 3 units to the right and 7 units upward.

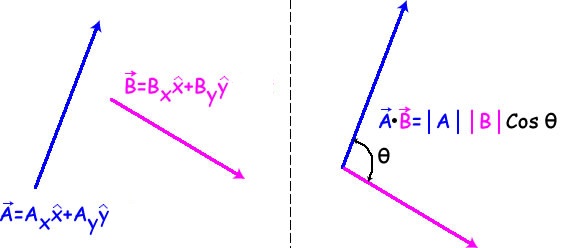

Dot Product of Two Vectors

The dot product of two vectors in \( \mathbb{R}^2 \) is a scalar quantity obtained by multiplying corresponding components and then adding the results.

If the vectors are

\( \langle a_1, b_1 \rangle \quad \text{and} \quad \langle a_2, b_2 \rangle \),

their dot product is defined as

\( \langle a_1, b_1 \rangle \cdot \langle a_2, b_2 \rangle = a_1a_2 + b_1b_2 \)

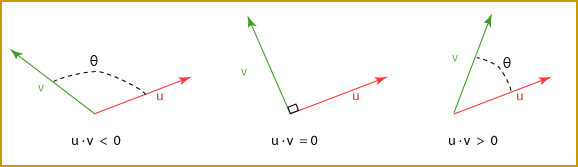

The dot product measures how much two vectors point in the same direction.

- If the dot product is positive, the vectors point generally in the same direction.

- If the dot product is negative, the vectors point in generally opposite directions.

- If the dot product is zero, the vectors are perpendicular.

The dot product can also be written using magnitudes and the angle \( \theta \) between the vectors:

\( \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v} = \lVert \mathbf{u} \rVert \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert \cos \theta \)

Example:

Find the dot product of the vectors \( \langle 3, 4 \rangle \) and \( \langle 2, -1 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Apply the dot product formula:

\( \langle 3, 4 \rangle \cdot \langle 2, -1 \rangle = (3)(2) + (4)(-1) = 6 – 4 = 2 \)

Conclusion: The dot product is 2, which is positive, so the vectors point generally in the same direction.

Example:

Determine whether the vectors \( \langle 5, 2 \rangle \) and \( \langle -2, 5 \rangle \) are perpendicular.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Compute the dot product:

\( \langle 5, 2 \rangle \cdot \langle -2, 5 \rangle = (5)(-2) + (2)(5) = -10 + 10 = 0 \)

Since the dot product is zero, the vectors are perpendicular.

Conclusion: The vectors meet at a right angle.

Unit Vectors

A unit vector is a vector whose magnitude is equal to 1.

Unit vectors are useful because they describe direction only, without regard to length.

If \( \mathbf{v} \) is a nonzero vector, then a unit vector in the same direction as \( \mathbf{v} \) is obtained by dividing the vector by its magnitude.![]()

If

\( \mathbf{v} = \langle a, b \rangle \),

then its magnitude is

\( \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \).

A unit vector in the direction of \( \mathbf{v} \) is

\( \mathbf{u} = \dfrac{1}{\lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert}\mathbf{v} = \left\langle \dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2}},\; \dfrac{b}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2}} \right\rangle \).

This process is called normalizing a vector.

The direction of the unit vector is the same as the original vector, but its length is exactly 1.

Example:

Find a unit vector in the direction of \( \langle 3, 4 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

First, find the magnitude:

\( \lVert \langle 3, 4 \rangle \rVert = \sqrt{3^2 + 4^2} = 5 \)

Multiply the vector by the reciprocal of its magnitude:

\( \dfrac{1}{5}\langle 3, 4 \rangle = \left\langle \dfrac{3}{5},\; \dfrac{4}{5} \right\rangle \)

Conclusion: The unit vector in the direction of \( \langle 3, 4 \rangle \) is \( \left\langle \dfrac{3}{5}, \dfrac{4}{5} \right\rangle \).

Example:

Find a unit vector in the direction of \( \langle -6, 8 \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Magnitude:

\( \sqrt{(-6)^2 + 8^2} = \sqrt{36 + 64} = 10 \)

Unit vector:

\( \dfrac{1}{10}\langle -6, 8 \rangle = \left\langle -\dfrac{3}{5},\; \dfrac{4}{5} \right\rangle \)

Conclusion: The unit vector has magnitude 1 and points in the same direction as the original vector.

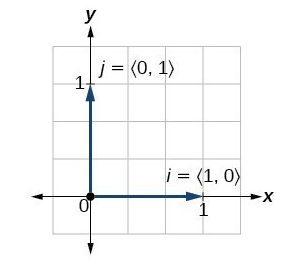

Unit Vectors i and j

In \( \mathbb{R}^2 \), vectors can be written using unit vectors in the coordinate directions.

The standard unit vectors are

\( \mathbf{i} = \langle 1, 0 \rangle \quad \text{and} \quad \mathbf{j} = \langle 0, 1 \rangle \)

Here, \( \mathbf{i} \) points one unit in the positive \( x \)-direction, and \( \mathbf{j} \) points one unit in the positive \( y \)-direction.

Any vector \( \langle a, b \rangle \) in the plane can be expressed as a linear combination of these unit vectors:

\( \langle a, b \rangle = a\mathbf{i} + b\mathbf{j} \)

This form emphasizes how much of the vector lies in the \( x \)-direction and how much lies in the \( y \)-direction.

Example:

Write the vector \( \langle 5, -2 \rangle \) in terms of \( \mathbf{i} \) and \( \mathbf{j} \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Use the unit vector form:

\( \langle 5, -2 \rangle = 5\mathbf{i} – 2\mathbf{j} \)

Conclusion: The vector has a horizontal component of 5 and a vertical component of −2.

Example:

Express the vector from the origin to the point \( (-3, 4) \) using \( \mathbf{i} \) and \( \mathbf{j} \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

The vector is \( \langle -3, 4 \rangle \).

\( \langle -3, 4 \rangle = -3\mathbf{i} + 4\mathbf{j} \)

Conclusion: The vector points left 3 units and up 4 units.

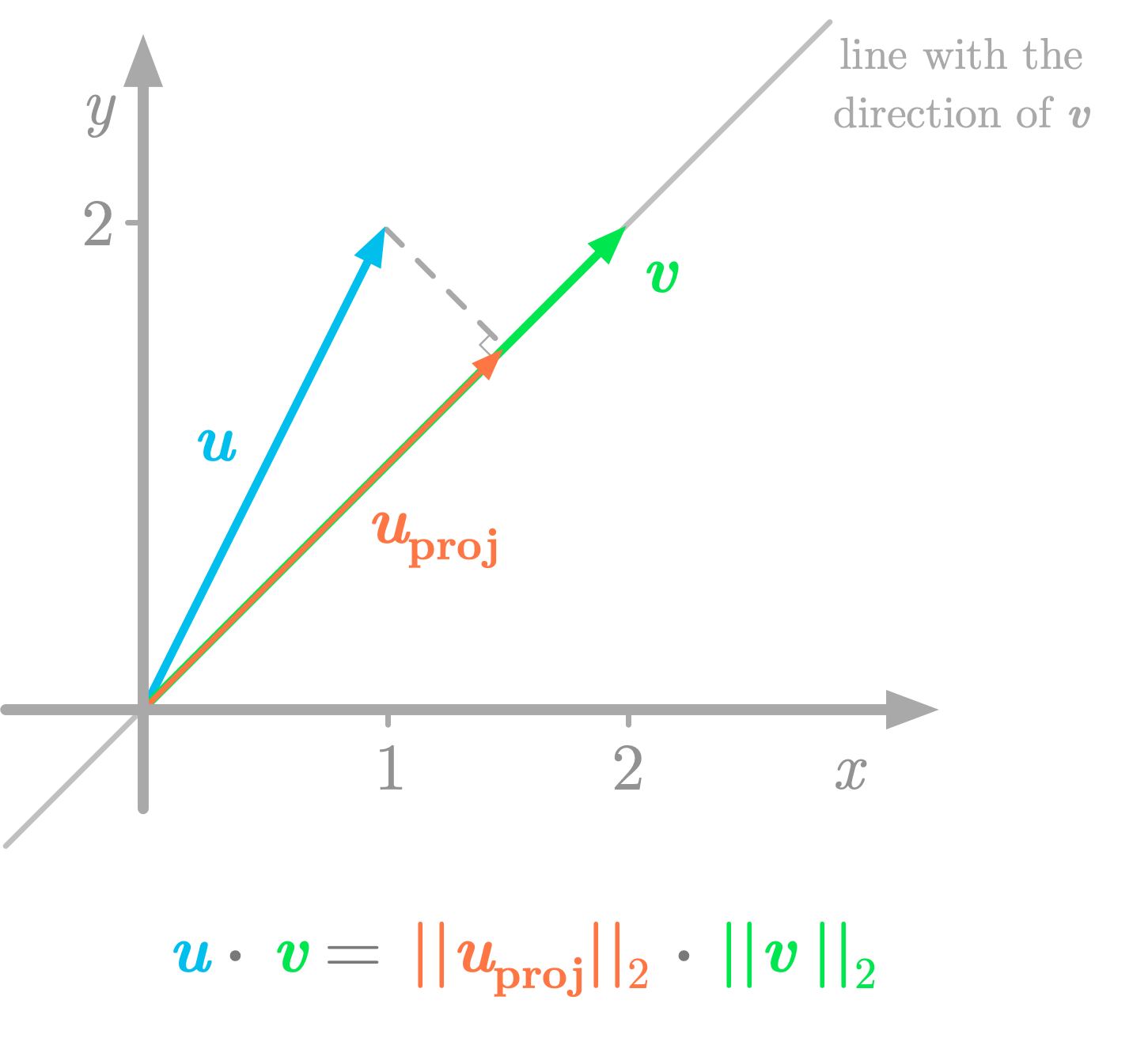

Geometric Interpretation of the Dot Product

The dot product of two nonzero vectors has a geometric meaning that relates their magnitudes and the angle between them.

If \( \mathbf{u} \) and \( \mathbf{v} \) are vectors with angle \( \theta \) between them, then the dot product can be written as

\( \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v} = \lVert \mathbf{u} \rVert \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert \cos \theta \)

This formula shows that the dot product measures how much one vector points in the direction of the other.

If the dot product of two nonzero vectors is zero, then

\( \lVert \mathbf{u} \rVert \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert \cos \theta = 0 \)

Since the magnitudes are nonzero, this implies

\( \cos \theta = 0 \)

Therefore, \( \theta = \dfrac{\pi}{2} \), and the vectors are perpendicular.

Thus, two nonzero vectors are perpendicular if and only if their dot product is zero.

Example:

Show that the vectors \( \langle 4, 1 \rangle \) and \( \langle -1, 4 \rangle \) are perpendicular.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Compute the dot product:

\( \langle 4, 1 \rangle \cdot \langle -1, 4 \rangle = (4)(-1) + (1)(4) = -4 + 4 = 0 \)

Since the dot product is zero, the vectors are perpendicular.

Conclusion: The angle between the vectors is \( 90^\circ \).

Example:

Find the angle between the vectors \( \mathbf{u} = \langle 3, 0 \rangle \) and \( \mathbf{v} = \langle 1, \sqrt{3} \rangle \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

First compute the dot product:

\( \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v} = (3)(1) + (0)(\sqrt{3}) = 3 \)

Find the magnitudes:

\( \lVert \mathbf{u} \rVert = 3,\quad \lVert \mathbf{v} \rVert = \sqrt{1 + 3} = 2 \)

Use the geometric dot product formula:

\( 3 = (3)(2)\cos \theta \)

\( \cos \theta = \dfrac{1}{2} \)

So \( \theta = \dfrac{\pi}{3} \).

Conclusion: The angle between the vectors is \( \dfrac{\pi}{3} \), so they are not perpendicular.

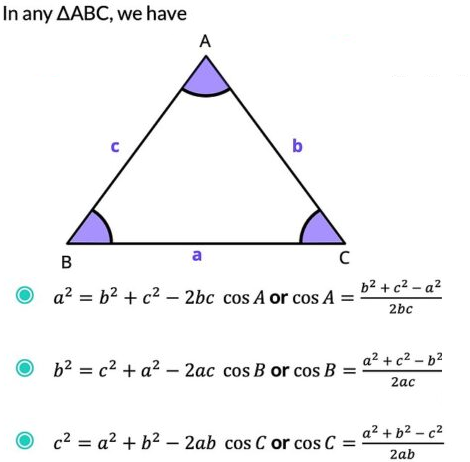

Law of Sines and Law of Cosines in Vector Addition

When vectors are added geometrically using the head-to-tail method, they form triangles in the plane. Classical triangle relationships can then be applied to analyze magnitudes and angles.![]()

Law of Sines

For any triangle with sides of lengths \( a \), \( b \), and \( c \) opposite angles \( A \), \( B \), and \( C \), respectively, the Law of Sines states:

\( \dfrac{a}{\sin A} = \dfrac{b}{\sin B} = \dfrac{c}{\sin C} \)

This relationship allows unknown side lengths or angle measures to be determined when sufficient information is known about the triangle formed by vector addition.

Law of Cosines

For any triangle with sides \( a \), \( b \), and \( c \) and opposite angles \( A \), \( B \), and \( C \), the Law of Cosines gives:

\( c^2 = a^2 + b^2 – 2ab\cos C \)

\( a^2 = b^2 + c^2 – 2bc\cos A \)

\( b^2 = a^2 + c^2 – 2ac\cos B \)

Formulas for Cosines of the Angles

Solving the Law of Cosines equations for the cosine of each angle gives:

\( \cos A = \dfrac{b^2 + c^2 – a^2}{2bc} \)

\( \cos B = \dfrac{a^2 + c^2 – b^2}{2ac} \)

\( \cos C = \dfrac{a^2 + b^2 – c^2}{2ab} \)

These formulas are especially useful in vector problems for finding the angle between two vectors when their magnitudes and the magnitude of their resultant are known.

Thus, the Law of Sines and the Law of Cosines provide a complete framework for determining both side lengths and angle measures in triangles formed by vector addition.

Example:

Two vectors form a triangle when added head to tail. One side of the triangle has length \( a = 8 \), the angle opposite this side is \( A = 40^\circ \), and another angle of the triangle is \( B = 65^\circ \). Find the length of the side \( b \) opposite angle \( B \).

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Use the Law of Sines:

\( \dfrac{a}{\sin A} = \dfrac{b}{\sin B} \)

Substitute the given values:

\( \dfrac{8}{\sin 40^\circ} = \dfrac{b}{\sin 65^\circ} \)

Solve for \( b \):

\( b = \dfrac{8\sin 65^\circ}{\sin 40^\circ} \)

\( b \approx \dfrac{8(0.9063)}{0.6428} \approx 11.28 \)

Conclusion: The length of the side opposite angle \( B \) is approximately \( 11.28 \) units.

Example:

Two vectors have magnitudes 6 and 10, and the angle between them is \( 60^\circ \). Find the magnitude of their resultant vector.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

The vectors form two sides of a triangle with included angle \( 60^\circ \).

Apply the Law of Cosines:

\( r^2 = 6^2 + 10^2 – 2(6)(10)\cos 60^\circ \)

\( r^2 = 36 + 100 – 120\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right) = 136 – 60 = 76 \)

\( r = \sqrt{76} = 2\sqrt{19} \)

Conclusion: The magnitude of the resultant vector is \( 2\sqrt{19} \).

Example:

Two vectors of magnitudes 5 and 7 form a triangle with a resultant vector of magnitude 9. Find the angle between the two vectors.

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Use the Law of Cosines, where the resultant vector is opposite the angle between the two vectors:

\( 9^2 = 5^2 + 7^2 – 2(5)(7)\cos \theta \)

\( 81 = 25 + 49 – 70\cos \theta \)

\( 81 = 74 – 70\cos \theta \)

\( 7 = -70\cos \theta \Rightarrow \cos \theta = -\dfrac{1}{10} \)

\( \theta = \arccos\left(-\dfrac{1}{10}\right) \)

Conclusion: The angle between the vectors is obtuse.