CIE AS/A Level Physics 15.3 Kinetic theory of gases Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Physics 15.3 Kinetic theory of gases Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Physics 15.3 Kinetic theory of gases Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Physics latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

- state the basic assumptions of the kinetic theory of gases

- explain how molecular movement causes the pressure exerted by a gas and derive and use the relationship $pV = \frac{1}{3}Nm<c^2>$, where $<c^2>$ is the mean-square speed (a simple model considering one-dimensional collisions and then extending to three dimensions using $\frac{1}{3}<c^2> = <c_x^2>$ is sufficient)

- understand that the root-mean-square speed $c_{r.m.s.}$ is given by $\sqrt{<c^2>}$

- compare $pV = \frac{1}{3}Nm<c^2>$ with $pV = NkT$ to deduce that the average translational kinetic energy of a molecule is $\frac{3}{2}kT$, and recall and use this expression

Basic Assumptions of the Kinetic Theory of Gases

The kinetic theory of gases explains the macroscopic behaviour of gases (pressure, temperature, volume) in terms of the microscopic behaviour of their molecules. The model is based on several fundamental assumptions:

- A gas consists of a very large number of molecules in constant, random motion.

- The volume of the gas molecules is negligible compared to the volume of the container. (Meaning: molecules are treated as point particles.)

- No intermolecular forces act except during collisions. (Particles do not attract or repel one another.)

- Collisions between molecules and with the container walls are perfectly elastic. (No kinetic energy is lost in collisions.)

- The time spent in collisions is negligible compared to the time spent travelling between collisions.

- Newton’s laws of motion apply to the molecules at all times.

- The average kinetic energy of the molecules is proportional to the thermodynamic temperature: \( \mathrm{\frac{1}{2}m\langle c^2\rangle \propto T} \)

These assumptions allow the development of the ideal gas equation and the kinetic model for pressure and temperature.

Example

Explain why intermolecular forces must be negligible in an ideal gas according to kinetic theory.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

If molecules exert forces on each other, they would attract or repel during motion, changing their speeds and kinetic energies. This would invalidate the assumption that pressure arises purely from elastic collisions with the container walls. Therefore, for the theory to hold, intermolecular forces must be negligible.

Example

Kinetic theory assumes the volume of gas molecules is negligible compared to the container. Explain when this assumption becomes invalid in real gases.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

At high pressures, molecules are forced very close together, so their finite volume becomes significant relative to the container volume. This makes the assumption of point-like particles invalid, and the gas deviates from ideal behaviour.

Example

Use the kinetic theory assumptions to explain why an ideal gas exerts pressure on the walls of a container.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The assumptions imply:

- Molecules move randomly with high speeds.

- They undergo perfectly elastic collisions with the walls.

- No forces act except during collisions.

When a molecule collides with a wall, it changes momentum. By Newton’s 2nd and 3rd laws, the wall experiences an equal and opposite force. Millions of collisions per second create a continuous average force per unit area—this is observed as gas pressure.

Thus, pressure originates from countless elastic molecular impacts.

Deriving the Pressure of an Ideal Gas from Molecular Motion

In kinetic theory, the pressure exerted by a gas is the direct result of countless collisions of gas molecules with the walls of the container. To derive the relationship

\( \mathrm{pV = \dfrac{1}{3} N m \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

we consider the motion of molecules and how their momentum changes when they collide with the walls.

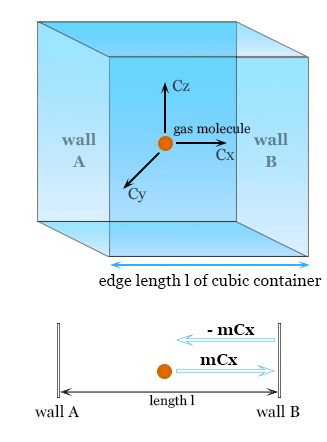

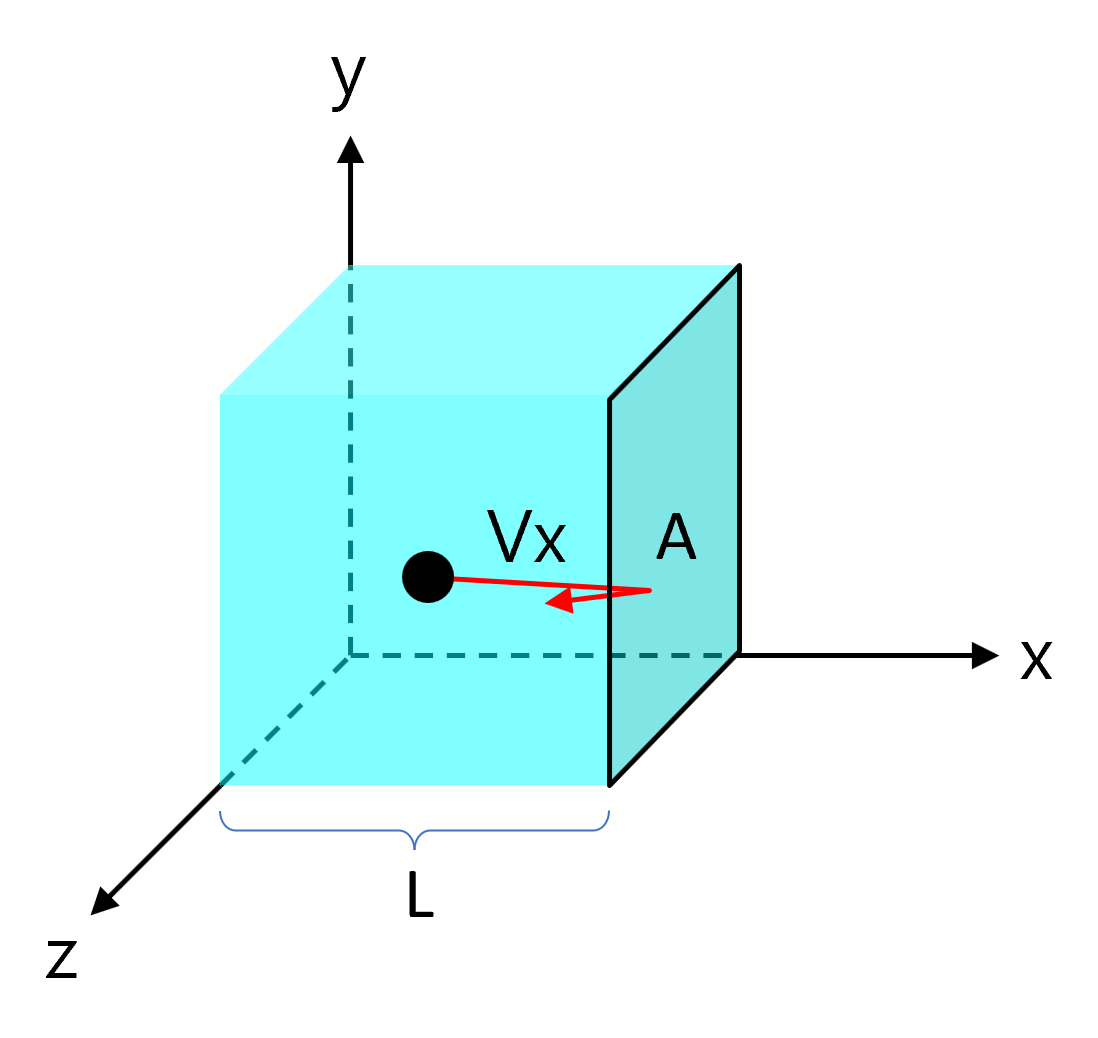

Step 1 — Consider 1D collisions

Take a cube of side length \( \mathrm{L} \) containing \( \mathrm{N} \) molecules, each of mass \( \mathrm{m} \). Choose one molecule with velocity component \( \mathrm{c_x} \) towards a wall.

Momentum change in collision:

- Before collision: momentum = \( \mathrm{mc_x} \)

- After elastic collision: momentum = \( \mathrm{-mc_x} \)

- Change in momentum = \( \mathrm{-mc_x – mc_x = -2mc_x} \)

By Newton’s 3rd law, the molecule exerts a force on the wall equal to the rate of change of momentum.

Time between successive collisions with the same wall:

\( \mathrm{\Delta t = \dfrac{2L}{c_x}} \)

Force contributed by one molecule:

\( \mathrm{F = \dfrac{\Delta p}{\Delta t} = \dfrac{2mc_x}{2L/c_x} = \dfrac{mc_x^2}{L}} \)

Pressure is force per unit area, and the wall area is \( \mathrm{A = L^2} \):

\( \mathrm{p = \dfrac{F}{A} = \dfrac{mc_x^2}{L^3}} = \mathrm{\dfrac{mc_x^2}{V}} \)

Step 2 — Sum over all molecules

The total pressure is:

\( \mathrm{p = \dfrac{m}{V} \sum c_x^2} \)

Define the mean-square x-velocity:

\( \mathrm{\langle c_x^2 \rangle = \dfrac{1}{N} \sum c_x^2} \)

Thus:

\( \mathrm{p = \dfrac{Nm \langle c_x^2 \rangle}{V}} \)

Step 3 — Extend to 3D motion

In three dimensions, the average energy is shared equally among x, y, and z directions.

\( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = \langle c_x^2 \rangle + \langle c_y^2 \rangle + \langle c_z^2 \rangle} \)

By symmetry: \( \mathrm{\langle c_x^2 \rangle = \langle c_y^2 \rangle = \langle c_z^2 \rangle} \), so each contributes one-third of the total:

\( \mathrm{\langle c_x^2 \rangle = \dfrac{1}{3} \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

Substitute this into the pressure expression:

\( \mathrm{p = \dfrac{Nm}{V} \cdot \dfrac{1}{3} \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

Multiply both sides by \( \mathrm{V} \):

\( \mathrm{pV = \dfrac{1}{3} N m \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

This is the kinetic theory expression for the pressure of an ideal gas.

Example

Explain why only the x-component of velocity is used when deriving pressure on one wall.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Pressure on a particular wall comes only from collisions with that wall. Only the velocity component perpendicular to that wall (the x-component) affects how often and how strongly molecules strike that wall. The y and z components cause movement parallel to the wall and contribute no momentum change toward it.

Example

In kinetic theory, three equal components of mean-square velocity are assumed. Explain why \( \mathrm{\langle c_x^2 \rangle = \langle c_y^2 \rangle = \langle c_z^2 \rangle} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The gas is assumed to be isotropic — the molecules move randomly in all directions with no preferred axis. Therefore, the average distribution of molecular velocities is the same in every direction. As a result, the mean-square speeds in x, y, and z must be equal.

Example

Use the equation \( \mathrm{pV = \dfrac{1}{3}Nm \langle c^2 \rangle} \) to show that increasing the mean-square speed of molecules increases the gas pressure.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The equation shows pressure is directly proportional to the mean-square speed:

\( \mathrm{p \propto \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

So, if the average molecular kinetic energy (and therefore \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \)) increases—for example by heating the gas—then:

- Molecules strike walls more frequently (higher collision rate).

- Each collision has a greater change in momentum (more force).

This produces a higher pressure. Thus, molecular motion directly determines gas pressure.

Root-Mean-Square Speed of Gas Molecules

The root-mean-square speed (r.m.s. speed) of gas molecules is a statistical measure of the average speed of particles in a gas. It is defined in terms of the mean-square speed \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \).

Definition:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{\langle c^2 \rangle}} \)

Meaning:

- \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \) is the average of the squared speeds of all molecules.

- The r.m.s. speed gives a measure of the “typical” molecular speed in a gas.

- It is always greater than the average speed, because squaring weights higher speeds more heavily.

- It relates molecular motion directly to temperature, since \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \propto T \).

Using the kinetic theory relation

\( \mathrm{pV = \dfrac{1}{3}Nm \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

we can connect pressure, temperature, and molecular speeds, eventually leading to:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{\dfrac{3kT}{m}}} \)

(Though this formula belongs to part 4, the definition itself is only \( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{\langle c^2 \rangle}} \).)

Example

A gas has mean-square molecular speed \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = 4.0\times 10^5\ m^2 s^{-2}} \). Calculate the r.m.s. speed.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{4.0\times 10^5}} \)

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = 632\ m/s} \)

Thus, the r.m.s. speed is \( \mathrm{6.3\times 10^2\ m/s} \).

Example

The r.m.s. speed of a gas is measured to be \( \mathrm{500\ m/s} \). Calculate the mean-square speed \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Using the definition:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms}^2 = \langle c^2 \rangle} \)

Thus:

\( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = 500^2 = 2.5\times 10^5\ m^2 s^{-2}} \)

Hence, the mean-square speed is \( \mathrm{2.5\times 10^5\ m^2 s^{-2}} \).

Example

Nitrogen molecules (\( \mathrm{m = 4.65\times 10^{-26}\ kg} \)) are at a temperature of \( \mathrm{300\ K} \). Using \( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{3kT/m}} \), calculate the r.m.s. speed.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the formula:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{\dfrac{3kT}{m}}} \)

Substitute values:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{\dfrac{3(1.38\times 10^{-23})(300)}{4.65\times 10^{-26}}}} \)

Calculate numerator:

\( \mathrm{3 \times 1.38\times 10^{-23} \times 300 = 1.242\times 10^{-20}} \)

Divide by mass:

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{1.242\times 10^{-20}}{4.65\times 10^{-26}} = 2.67\times 10^{5}} \)

Now square root:

\( \mathrm{c_{rms} = \sqrt{2.67\times 10^{5}} = 517\ m/s} \)

The r.m.s. speed ≈ \( \mathrm{5.2\times 10^2\ m/s} \).

Average Translational Kinetic Energy of a Gas Molecule

We now compare the kinetic theory equation

\( \mathrm{pV = \dfrac{1}{3}Nm\langle c^2 \rangle} \)

with the ideal gas equation in molecular form:

\( \mathrm{pV = NkT} \)

Since both expressions equal \( \mathrm{pV} \), we equate them:

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{1}{3}Nm\langle c^2 \rangle = NkT} \)

Cancel \( \mathrm{N} \) from both sides:

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{1}{3}m\langle c^2 \rangle = kT} \)

Rearrange for the molecular kinetic energy term:

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{1}{2} m\langle c^2 \rangle = \dfrac{3}{2}kT} \)

This shows:

\( \mathrm{E_{k(avg)} = \dfrac{3}{2}kT} \)

Meaning:

- The average translational kinetic energy of a molecule depends only on the temperature.

- It is the same for all ideal gases at the same temperature, regardless of their mass.

- A higher temperature means greater molecular motion.

Important insight:

Temperature is a direct measure of the average kinetic energy of molecules.

Example

Calculate the average molecular kinetic energy at \( \mathrm{T = 300\ K} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use: \( \mathrm{E_k = \dfrac{3}{2}kT} \)

\( \mathrm{E_k = \dfrac{3}{2}(1.38\times10^{-23})(300)} \)

\( \mathrm{E_k = 6.21\times10^{-21}\ J} \)

Average kinetic energy = \( \mathrm{6.2\times10^{-21}\ J} \)

Example

By what factor does the average kinetic energy increase when the temperature rises from \( \mathrm{200\ K} \) to \( \mathrm{600\ K} \)?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Using: \( \mathrm{E_k \propto T} \)

\( \mathrm{\dfrac{E_{k2}}{E_{k1}} = \dfrac{T_2}{T_1} = \dfrac{600}{200} = 3} \)

The average kinetic energy triples.

Example

A gas contains molecules each of mass \( \mathrm{5.0\times10^{-26}\ kg} \) at temperature \( \mathrm{T = 400\ K} \). Calculate the mean-square speed \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle} \) using the kinetic energy expression.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use: \( \mathrm{\dfrac{1}{2} m\langle c^2 \rangle = \dfrac{3}{2}kT} \)

Rearrange:

\( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = \dfrac{3kT}{m}} \)

Substitute values:

\( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = \dfrac{3(1.38\times10^{-23})(400)}{5.0\times10^{-26}}} \)

Calculate numerator:

\( \mathrm{3 \times 1.38\times10^{-23} \times 400 = 1.656\times10^{-20}} \)

Divide:

\( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = \dfrac{1.656\times10^{-20}}{5.0\times10^{-26}} = 3.31\times10^{5}} \)

Thus, \( \mathrm{\langle c^2 \rangle = 3.3\times10^{5}\ m^2s^{-2}} \).