CIE AS/A Level Physics 20.3 Force on a moving charge Study Notes- 2025-2027 Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Physics 20.3 Force on a moving charge Study Notes – New Syllabus

CIE AS/A Level Physics 20.3 Force on a moving charge Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on AS/A Level Physics latest syllabus with Candidates should be able to:

- determine the direction of the force on a charge moving in a magnetic field

- recall and use \( F = B Q v \sin \theta \)

- understand the origin of the Hall voltage and derive and use the expression \( V_h = B I / (n t q) \), where ( t ) = thickness

- understand the use of a Hall probe to measure magnetic flux density

- describe the motion of a charged particle moving in a uniform magnetic field perpendicular to the direction of motion of the particle

- explain how electric and magnetic fields can be used in velocity selection

Direction of Force on a Moving Charge in a Magnetic Field

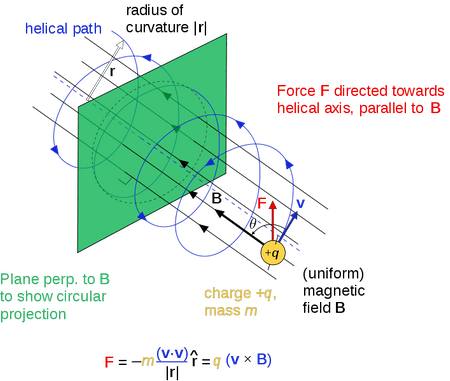

A charged particle moving through a magnetic field experiences a force. This force is always perpendicular to both:![]()

- the direction of motion of the charge, and

- the magnetic field direction.

This is known as the motor effect for charges.

Right-Hand Rule for Positive Charges

Thumb → direction of velocity (motion of the charge) First finger → direction of magnetic field (from N to S) Middle finger → direction of force

Important: For a negative charge, the force direction is opposite to that predicted by the right-hand rule.

Key Points:

- A stationary charge in a magnetic field feels no force (because velocity = 0).

- Force is maximum when velocity is perpendicular to the field.

- Force is zero when the charge moves parallel to the field (θ = 0° or 180°).

- The force causes charges to move in a circular or helical path.

Magnitude of Force:

\( \mathrm{F = Bqv\sin\theta} \)

Example

A positive charge moves to the right through a magnetic field directed into the page. What is the direction of the force?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the right-hand rule:

- Thumb → right (velocity)

- First finger → into page (field)

- Middle finger → points upward

Force acts upward.

Example

An electron moves north in a magnetic field directed east. Determine the direction of the force on the electron.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

For a positive charge using right-hand rule:

- Thumb → north (velocity)

- First finger → east (field)

- Middle finger → points downward

But the charge is an electron, so reverse the direction:

Force acts upward.

Example

A proton moves at 90° to a magnetic field and experiences a force that deflects it out of the page. If the proton’s velocity is upward, determine the direction of the magnetic field.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The force direction is out of the page.

Using right-hand rule (positive charge):

- Middle finger → out of page (force)

- Thumb → upward (velocity)

- First finger must point → left

The magnetic field is directed to the left.

Force on a Moving Charge: \( \mathrm{F = BQv \sin\theta} \)

A charged particle moving through a magnetic field experiences a magnetic force. The size of this force is given by:

\( \mathrm{F = B Q v \sin\theta} \)

- \( \mathrm{F} \) = magnetic force (N)

- \( \mathrm{B} \) = magnetic flux density (T)

- \( \mathrm{Q} \) = charge of particle (C)

- \( \mathrm{v} \) = speed of particle (m s⁻¹)

- \( \mathrm{\theta} \) = angle between velocity and magnetic field

Key Understanding:

- Force is maximum when the charge moves perpendicular to the field (\( \mathrm{\theta = 90^\circ} \), \( \mathrm{\sin\theta = 1} \)).

- Force is zero when the charge moves parallel to the field (\( \mathrm{\theta = 0^\circ} \), \( \mathrm{\sin\theta = 0} \)).

- Force acts perpendicular to both the velocity and the magnetic field → resulting in circular or helical motion.

- Direction is determined using the right-hand rule (reverse for negative charges).

Example

An electron moves at \( \mathrm{3.0\times10^6\ m\,s^{-1}} \) perpendicular to a magnetic field of \( \mathrm{0.40\ T} \). The charge on the electron is \( \mathrm{1.6\times10^{-19}\ C} \). Find the magnitude of the force.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Since the motion is perpendicular, \( \mathrm{\sin\theta = 1} \).

\( \mathrm{F = BQv = 0.40 \times 1.6\times10^{-19} \times 3.0\times10^6} \)

\( \mathrm{F = 1.92\times10^{-13}\ N} \)

Force = \( \mathrm{1.9\times10^{-13}\ N} \)

Example

A proton moves at an angle of 60° to a magnetic field of 0.20 T. Its speed is \( \mathrm{2.5\times10^5\ m\,s^{-1}} \) and charge is \( \mathrm{1.6\times10^{-19}\ C} \). Calculate the force on it.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{F = BQv \sin\theta} \)

\( \mathrm{F = 0.20 \times 1.6\times10^{-19} \times 2.5\times10^5 \times \sin 60^\circ} \)

Since \( \mathrm{\sin 60^\circ = 0.866} \):

\( \mathrm{F = 0.20 \times 1.6\times10^{-19} \times 2.5\times10^5 \times 0.866} \)

\( \mathrm{F \approx 6.9\times10^{-15}\ N} \)

Force ≈ \( \mathrm{6.9\times10^{-15}\ N} \)

Example

An alpha particle (charge \( \mathrm{+3.2\times10^{-19}\ C} \)) moves at \( \mathrm{5.0\times10^6\ m\,s^{-1}} \) through a magnetic field of \( \mathrm{0.15\ T} \). The angle between its velocity and the field is 30°. Calculate the magnetic force.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{F = BQv \sin\theta} \)

\( \mathrm{F = 0.15 \times 3.2\times10^{-19} \times 5.0\times10^6 \times \sin 30^\circ} \)

Since \( \mathrm{\sin 30^\circ = 0.5} \):

\( \mathrm{F = 0.15 \times 3.2\times10^{-19} \times 5.0\times10^6 \times 0.5} \)

\( \mathrm{F = 1.2\times10^{-13}\ N} \)

Force = \( \mathrm{1.2\times10^{-13}\ N} \)

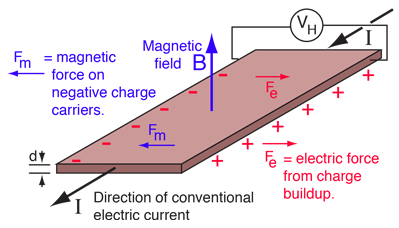

The Hall Effect and the Hall Voltage

The Hall effect occurs when a current-carrying conductor or semiconductor is placed in a magnetic field that is perpendicular to the direction of the current. The moving charge carriers experience a magnetic force that pushes them to one side of the material, creating a measurable potential difference called the Hall voltage.

Origin of the Hall Voltage

- Consider a flat conductor of thickness \( \mathrm{t} \) carrying a current \( \mathrm{I} \) in one direction.

- A magnetic field \( \mathrm{B} \) is applied perpendicular to the current.

- Charge carriers (electrons for metals, holes for p-type semiconductors) move with drift velocity \( \mathrm{v_d} \).

- The magnetic field exerts a force on each moving charge:

\( \mathrm{F = BQv_d} \)

- This force pushes the charges sideways.

- Charges accumulate on one side → one side becomes negatively charged, the opposite side positively charged.

- This separation of charge creates an electric field called the Hall field.

- A potential difference (Hall voltage \( \mathrm{V_H} \)) develops across the conductor.

- The Hall voltage increases until electric force balances magnetic force.

Balance Condition:

Magnetic force = Electric force \( \mathrm{B Q v_d = Q E_H} \)

So:

\( \mathrm{E_H = B v_d} \)

The Hall voltage is:

\( \mathrm{V_H = E_H \, t = B v_d t} \)

Derivation of the Hall Voltage Formula

![]()

Current is given by:

\( \mathrm{I = n A Q v_d} \)

- \( \mathrm{n} \) = number density of charge carriers (m⁻³)

- \( \mathrm{A} \) = cross-sectional area

- \( \mathrm{Q} \) = charge of each carrier

- \( \mathrm{v_d} \) = drift velocity

For a slab of width \( \mathrm{w} \) and thickness \( \mathrm{t} \):

\( \mathrm{A = w t} \)

Thus:

\( \mathrm{v_d = \dfrac{I}{n w t Q}} \)

Substitute into \( \mathrm{V_H = B v_d t} \):

\( \mathrm{V_H = B \left(\dfrac{I}{n w t Q}\right)t} \)

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{B I}{n Q w}} \)

For a strip where width \( \mathrm{w} \) is not involved in measurement, we write the final standard form:

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{B I}{n t Q}} \)

- \( \mathrm{V_H} \) = Hall voltage

- \( \mathrm{B} \) = magnetic flux density

- \( \mathrm{I} \) = current

- \( \mathrm{n} \) = carrier number density

- \( \mathrm{t} \) = thickness of the conductor

- \( \mathrm{Q} \) = charge of carrier (usually \( \mathrm{e = 1.6\times10^{-19}\ C} \))

Example

A conductor of thickness \( \mathrm{2.0\times10^{-3}\ m} \) carries a current of 4 A in a magnetic field of 0.50 T. The charge carrier density is \( \mathrm{8.0\times10^{28}\ m^{-3}} \). Find the Hall voltage.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{B I}{n t Q}} \)

Substitute:

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{0.50 \times 4}{(8.0\times10^{28})(2.0\times10^{-3})(1.6\times10^{-19})}} \)

\( \mathrm{V_H = 7.8\times10^{-9}\ V} \)

Hall voltage = \( \mathrm{7.8\times10^{-9}\ V} \)

Example

If the magnetic field is doubled in the previous example, what happens to the Hall voltage?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The formula is:

\( \mathrm{V_H \propto B} \)

So doubling \( \mathrm{B} \) doubles \( \mathrm{V_H} \).

New Hall voltage = \( \mathrm{1.56\times10^{-8}\ V} \)

Example

A thin semiconductor slice of thickness \( \mathrm{1.0\times10^{-4}\ m} \) carries a current of 12 A. A magnetic field of 0.80 T is applied perpendicular to the slice. The measured Hall voltage is \( \mathrm{0.040\ V} \). Determine the number density of charge carriers.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{n = \dfrac{B I}{t Q V_H}} \)

Substitute:

\( \mathrm{n = \dfrac{0.80 \times 12}{(1.0\times10^{-4})(1.6\times10^{-19})(0.040)}} \)

\( \mathrm{n = 1.5\times10^{23}\ m^{-3}} \)

Carrier density = \( \mathrm{1.5\times10^{23}\ m^{-3}} \)

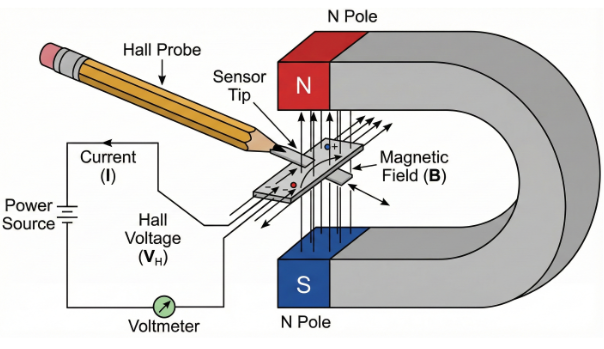

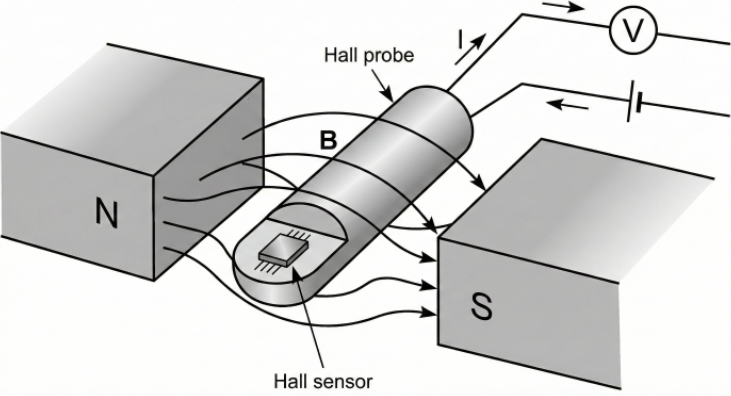

Use of a Hall Probe to Measure Magnetic Flux Density

A Hall probe is a device that uses the Hall effect to measure the strength of a magnetic field (magnetic flux density, \( \mathrm{B} \)). It works by detecting the Hall voltage produced when a current-carrying conductor or semiconductor is placed in a magnetic field.

How a Hall Probe Works

- A thin semiconductor strip is supplied with a constant current \( \mathrm{I} \).

- When the strip is placed in a magnetic field perpendicular to the current direction, the Hall effect causes a sideways force on moving charge carriers.

- This creates a measurable potential difference — the Hall voltage \( \mathrm{V_H} \) — across the strip.

- The Hall voltage is proportional to the magnetic flux density:

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{B I}{n t q}} \)

By measuring \( \mathrm{V_H} \), the Hall probe can determine \( \mathrm{B} \) accurately.

Using a Hall Probe

- The Hall probe is placed so that its sensing surface is perpendicular to the magnetic field.

- The probe is connected to a voltmeter or electronic meter that reads the Hall voltage.

- The device is often calibrated so that it directly displays magnetic flux density in tesla (T) or millitesla (mT).

- The reading changes sign depending on field direction (north–south reversal).

Orientation Matters:

Maximum reading occurs when the plane of the Hall element is at right-angles to the magnetic field. If the probe is tilted, the measured flux density decreases according to \( \mathrm{B\cos\theta} \).

Advantages of a Hall Probe

- Can measure strong magnetic fields where compasses or iron filings fail.

- Allows measurement of magnitude and direction of the field.

- Very sensitive (especially semiconductor probes).

- Can measure rapidly changing magnetic fields.

Example

A Hall probe is placed in a magnetic field and its sensing face is perpendicular to the field. Why is this orientation necessary?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The Hall voltage is proportional to the perpendicular component of the magnetic field. To maximise the Hall effect (and reading), the sensing surface must be at right-angles to the field.

Example

A Hall probe gives a reading of 0.32 mT when oriented correctly in a magnetic field. When it is tilted so that the face is at 60° to the field, what reading will it give?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Only the perpendicular component is measured:

\( \mathrm{B_{\text{measured}} = B \cos\theta} \)

\( \mathrm{B_{\text{measured}} = 0.32\times10^{-3} \times \cos 60^\circ} \)

\( \mathrm{= 0.32\times10^{-3} \times 0.5 = 0.16\ mT} \)

Measured field = 0.16 mT

Example

A Hall probe uses a semiconductor of thickness \( \mathrm{1.5\times10^{-4}\ m} \) with charge carrier density \( \mathrm{4.0\times10^{22}\ m^{-3}} \). A constant current of 18 mA flows through the probe. In a certain magnetic field, the Hall voltage measured is 0.020 V. Calculate the magnetic flux density.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use the Hall voltage formula:

\( \mathrm{V_H = \dfrac{B I}{n t q}} \)

Rearrange:

\( \mathrm{B = \dfrac{V_H \, n t q}{I}} \)

Substitute:

\( \mathrm{B = \dfrac{0.020 \times (4.0\times10^{22}) \times (1.5\times10^{-4}) \times (1.6\times10^{-19})}{18\times10^{-3}}} \)

\( \mathrm{B = 1.07\ T} \)

Magnetic flux density ≈ 1.07 T

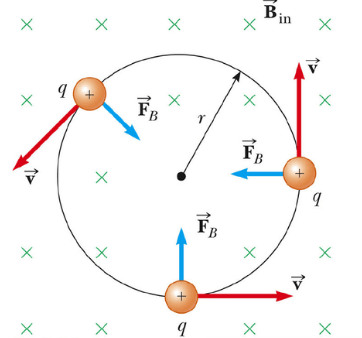

Motion of a Charged Particle in a Uniform Magnetic Field (Perpendicular Entry)

When a charged particle moves into a uniform magnetic field perpendicular to its velocity, it experiences a magnetic force that is always perpendicular to its motion.

This perpendicular force causes the particle to move in a circular path.

Why Circular Motion Occurs

- The magnetic force on a moving charge is:

\( \mathrm{F = BQv} \)

- This force is always perpendicular to the velocity.

- A force perpendicular to velocity does not change speed — only direction.

- Thus, the magnetic force acts as a centripetal force.

\( \mathrm{BQv = \dfrac{mv^2}{r}} \)

The resulting path is a uniform circle.

Radius of the Circular Path

\( \mathrm{r = \dfrac{mv}{BQ}} \)

- Lighter particles → smaller radius

- Faster particles → larger radius

- Stronger magnetic field → tighter circle

- Greater charge → tighter circle

Key Characteristics of the Motion

- Speed remains constant (force is perpendicular to motion).

- Velocity direction changes continuously → circular motion.

- Angular speed \( \mathrm{\omega = \dfrac{v}{r} = \dfrac{BQ}{m}} \)

- Time period:

\( \mathrm{T = \dfrac{2\pi m}{BQ}} \)

- Direction of rotation depends on charge sign:

- Positive charge → direction given by right-hand rule

- Negative charge → rotates in opposite direction

Example

A proton enters a uniform magnetic field perpendicular to its velocity. Describe its motion.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The proton experiences a force perpendicular to its velocity, causing it to move in a circular path. Its speed remains constant, but its direction changes continuously.

Example

An electron enters a magnetic field at 90° to the field lines. How is its circular motion different from that of a proton?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

- An electron has a negative charge → force direction reverses.

- The electron moves in the opposite sense (clockwise/anticlockwise) compared to the proton.

- Because the electron has a much smaller mass, its radius

\( \mathrm{r = \dfrac{mv}{BQ}} \)

is much smaller.

The electron travels in a smaller circle and opposite direction to a proton.

Example

An alpha particle (\( \mathrm{Q = 3.2 \times 10^{-19}\ C} \)) with speed \( \mathrm{1.0\times10^6\ m\,s^{-1}} \) enters a \( \mathrm{0.40\ T} \) magnetic field perpendicular to its motion. Calculate the radius of its circular path. (The mass of an alpha particle is \( \mathrm{6.64\times10^{-27}\ kg} \)).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{r = \dfrac{mv}{BQ}} \)

\( \mathrm{r = \dfrac{6.64\times10^{-27} \times 1.0\times10^6}{0.40 \times 3.2\times10^{-19}}} \)

\( \mathrm{r = \dfrac{6.64\times10^{-21}}{1.28\times10^{-19}}} \)

\( \mathrm{r = 0.052\ m} \)

Radius = 0.052 m

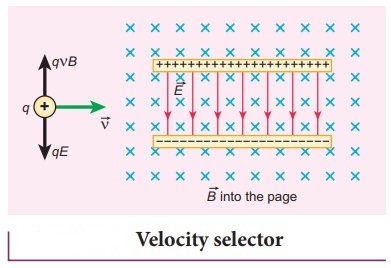

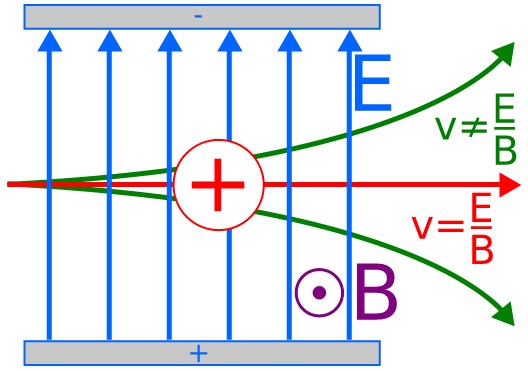

Velocity Selection Using Electric and Magnetic Fields

A velocity selector uses crossed electric and magnetic fields to allow only charged particles with a specific velocity to pass through undeflected. All other particles experience a net force and are deflected away.

How Velocity Selection Works

- A uniform electric field \( \mathrm{E} \) is applied between two parallel plates → produces an electric force

\( \mathrm{F_E = QE} \)

- A uniform magnetic field \( \mathrm{B} \) is applied perpendicular to both the plates and the particle motion → produces a magnetic force

\( \mathrm{F_B = BQv} \)

- The two forces act in opposite directions.

Condition for no deflection:

\( \mathrm{F_E = F_B} \)

Substitute:

\( \mathrm{QE = BQv} \)

Cancel \( \mathrm{Q} \):

\( \mathrm{v = \dfrac{E}{B}} \)

Only particles with velocity \( \mathrm{v = E/B} \) travel straight.

Slower or faster particles experience a net force and are deflected away.

Key Features of a Velocity Selector:

- Works only when \( \mathrm{E} \) and \( \mathrm{B} \) fields are perpendicular to each other and to particle motion.

- The selected velocity does not depend on charge or mass → only on \( \mathrm{E/B} \).

- Used in mass spectrometers and particle accelerators.

Applications:

- Mass spectrometer — ensures all ions entering the magnetic chamber have the same velocity.

- Charged particle detection — isolate particles of a specific speed.

- Plasma experiments — control particle streams.

Example

A proton enters a velocity selector and moves undeflected. What does this tell you about its speed?

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The electric and magnetic forces are balanced. Thus, the proton’s speed is:

\( \mathrm{v = \dfrac{E}{B}} \)

Its velocity matches the selector’s chosen speed.

Example

A velocity selector has an electric field of \( \mathrm{4.0\times10^4\ V\,m^{-1}} \) and a magnetic field of \( \mathrm{0.20\ T} \). Find the velocity of particles that will pass through undeflected.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Use:

\( \mathrm{v = \dfrac{E}{B}} \)

\( \mathrm{v = \dfrac{4.0\times10^4}{0.20} = 2.0\times10^5\ m\,s^{-1}} \)

Selected velocity = \( \mathrm{2.0\times10^5\ m\,s^{-1}} \)

Example

An ion enters a velocity selector with electric field \( \mathrm{6.0\times10^4\ V\,m^{-1}} \) and magnetic field \( \mathrm{0.30\ T} \). If the ion is observed to bend upward, determine whether its speed is too high or too low.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The electric field pushes charges in one direction; the magnetic field pushes them in the opposite direction.

If the ion bends upward, it means:

- One of the forces is stronger → imbalance.

- If the magnetic force dominates, the ion curves in the magnetic-force direction.

Since magnetic force = \( \mathrm{BQv} \):

If bending occurs, \( \mathrm{BQv > QE} \) → \( \mathrm{v > \dfrac{E}{B}} \).

The ion’s speed is greater than the selected velocity.