IB Mathematics AHL 5.13 The evaluation of limits AA HL Paper 3

Question

Informally, the curvature of a curve can be thought of as the amount by which the curve deviates from being a straight line. In this problem, you will examine the curvature of several types of functions.

For any function \( f \) that is twice differentiable, the curvature \( k \) is defined by \[ k(x) = \frac{|f”(x)|}{\bigl(1 + (f'(x))^2\bigr)^{3/2}}. \]

(a) Consider the family of linear functions \( g(x) = mx + c \), where \( m, c \in \mathbb{R} \). Show that for these functions, \( k(x) = 0 \) for all \( x \).

(b) Now consider the family of quadratic functions \( h(x) = ax^2 + bx + c \) with \( a \neq 0 \). For these functions it is given that \[ k(x) = \frac{2|a|}{\bigl(1 + (2ax + b)^2\bigr)^{3/2}}, \qquad k'(x) = -\frac{12a|a|(2ax + b)}{\bigl(1 + (2ax + b)^2\bigr)^{5/2}}. \] Let \( k_{\max} \) denote the maximum value of \( k(x) \).

(i) By solving \( k'(x) = 0 \), find the value of \( x \) at which \( k_{\max} \) occurs.

(ii) Hence determine an expression for \( k_{\max} \) in terms of \( a \) only.

(iii) State the value of \( \displaystyle \lim_{x \to \infty} k(x) \) and give a brief interpretation of this result.

(iv) For the two quadratic functions \[ p(x) = -2x^2 + 2x – 10 \quad \text{and} \quad q(x) = 2x^2 + 5x + 25, \] state which of the following is true and justify your choice:

A. \( k_{\max} \) of \( p \) > \( k_{\max} \) of \( q \) B. \( k_{\max} \) of \( p \) < \( k_{\max} \) of \( q \) C. \( k_{\max} \) of \( p \) = \( k_{\max} \) of \( q \)

(c) Consider the function \( v(x) = \ln x \) for \( x > 0 \). For this function, \[ k(x) = \frac{x}{(1 + x^2)^{3/2}}, \qquad k'(x) = \frac{1 – 2x^2}{(1 + x^2)^{5/2}}. \]

(i) Determine the exact value of \( x \) where \( k_{\max} \) occurs.

(ii) Show that \( k_{\max} = \dfrac{2\sqrt{3}}{9} \).

(d) Consider the function \( w(x) = e^{x} \). For this function, \[ k(x) = \frac{e^{x}}{(1 + e^{2x})^{3/2}}, \qquad k'(x) = \frac{e^{x}(1 – 2e^{2x})}{(1 + e^{2x})^{5/2}}. \]

(i) Show that \( k_{\max} = \dfrac{2\sqrt{3}}{9} \).

(ii) Suggest a reason why \( v \) and \( w \) have the same maximum curvature.

(e) Consider the family of curves \( y = \sqrt{r^{2} – x^{2}} \) where \( -r < x < r, \; y > 0 \) and \( r > 0 \).

(i) Show that \( \displaystyle \frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \).

(ii) Hence show that the curvature \( k \) is constant for this family of curves.

Most‑appropriate topic codes (IB Mathematics: analysis and approaches AHL):

• AHL 5.13: Limits of the form \(\frac{\infty}{\infty}\) and horizontal asymptotes — part (b)(iii)

• AHL 5.14: Implicit differentiation and optimization problems — parts (b), (e)

• AHL 2.14: Inverse functions and their geometric properties — part (d)(ii)

▶️ Answer/Explanation

(a)

For \( g(x) = mx + c \), we have \( g'(x) = m \) and \( g”(x) = 0 \).

Hence \( k(x) = \frac{|0|}{(1 + m^{2})^{3/2}} = 0 \).

\( \boxed{k(x)=0} \)

(b)

(i) Setting \( k'(x) = 0 \) gives

\( -\dfrac{12a|a|(2ax+b)}{(1+(2ax+b)^{2})^{5/2}} = 0 \Rightarrow 2ax + b = 0 \Rightarrow x = -\dfrac{b}{2a} \).

\( \boxed{x = -\frac{b}{2a}} \)

(ii) Substitute \( x = -\frac{b}{2a} \) into \( k(x) \):

\( k_{\max} = \dfrac{2|a|}{(1 + (2a(-\frac{b}{2a}) + b)^{2})^{3/2}} = \dfrac{2|a|}{(1 + 0)^{3/2}} = 2|a| \).

\( \boxed{k_{\max}=2|a|} \)

(iii) As \( x \to \infty \), the denominator \( (1+(2ax+b)^{2})^{3/2} \to \infty \), so \( k(x) \to 0 \).

Interpretation: For large \( |x| \), a quadratic function becomes almost straight (its curvature tends to zero).

\( \boxed{\lim_{x\to\infty}k(x)=0} \)

(iv) For \( p(x) \), \( a = -2 \Rightarrow |a| = 2 \); for \( q(x) \), \( a = 2 \Rightarrow |a| = 2 \).

Hence \( k_{\max}(p) = 2|{-2}| = 4 \) and \( k_{\max}(q) = 2|2| = 4 \). So \( k_{\max} \) is equal.

\( \boxed{\text{C}} \)

(c)

(i) Set \( k'(x) = 0 \): \( \dfrac{1-2x^{2}}{(1+x^{2})^{5/2}} = 0 \Rightarrow 1-2x^{2}=0 \Rightarrow x^{2}=\frac12 \Rightarrow x = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \) (positive since \( x>0 \)).

\( \boxed{x = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}} \)

(ii) Substitute \( x = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \) into \( k(x) \):

\( k_{\max} = \dfrac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{\bigl(1 + (\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})^{2}\bigr)^{3/2}} = \dfrac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{\bigl(\frac{3}{2}\bigr)^{3/2}} = \dfrac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{2\sqrt{2}}} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \cdot \dfrac{2\sqrt{2}}{3\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{2\sqrt{3}}{9}. \)

\( \boxed{k_{\max} = \frac{2\sqrt{3}}{9}} \)

(d)

(i) Set \( k'(x) = 0 \): \( \dfrac{e^{x}(1-2e^{2x})}{(1+e^{2x})^{5/2}} = 0 \Rightarrow 1-2e^{2x}=0 \Rightarrow e^{2x} = \frac12 \Rightarrow e^{x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \).

Substitute \( e^{x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \) into \( k(x) \):

\( k_{\max} = \dfrac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{\bigl(1+(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})^{2}\bigr)^{3/2}} = \dfrac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}{(\frac{3}{2})^{3/2}} = \dfrac{2}{3\sqrt{3}} = \dfrac{2\sqrt{3}}{9} \).

\( \boxed{k_{\max} = \frac{2\sqrt{3}}{9}} \)

(ii) The functions \( v(x)=\ln x \) and \( w(x)=e^{x} \) are inverses of each other. Their graphs are reflections in the line \( y=x \), so they have the same “shape” and therefore the same maximum curvature.

\( \boxed{\text{They are inverse functions}} \)

(e)

(i) Method 1 (Implicit differentiation):

\( y^{2} = r^{2} – x^{2} \). Differentiate implicitly: \( 2y\frac{dy}{dx} = -2x \Rightarrow \frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{x}{y} \).

Differentiate again using the quotient rule:

\( \frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{y\cdot 1 – x\frac{dy}{dx}}{y^{2}} = -\frac{y – x(-\frac{x}{y})}{y^{2}} = -\frac{y^{2}+x^{2}}{y^{3}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \).

Method 2 (Chain rule):

\( y = (r^{2}-x^{2})^{1/2} \Rightarrow \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac12 (r^{2}-x^{2})^{-1/2}(-2x) = -\frac{x}{\sqrt{r^{2}-x^{2}}} = -\frac{x}{y} \).

Then \( \frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{y – x\frac{dy}{dx}}{y^{2}} = -\frac{y – x(-\frac{x}{y})}{y^{2}} = -\frac{y^{2}+x^{2}}{y^{3}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \). Noah, since \( r^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2} \).

Method 3 (Product rule on first derivative):

From \( y\frac{dy}{dx} = -x \), differentiate implicitly: \( \bigl(\frac{dy}{dx}\bigr)^{2} + y\frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -1 \).

Substitute \( \frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{x}{y} \): \( \frac{x^{2}}{y^{2}} + y\frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -1 \Rightarrow y\frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -1 – \frac{x^{2}}{y^{2}} = -\frac{y^{2}+x^{2}}{y^{2}} \).

Hence \( \frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{y^{2}+x^{2}}{y^{3}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \).

\( \boxed{\frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}}} \)

(ii) Substitute \( \frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{x}{y} \) and \( \frac{d^{2}y}{dx^{2}} = -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \) into the curvature formula:

\( k = \dfrac{\bigl| -\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}} \bigr|}{\bigl(1 + (-\frac{x}{y})^{2}\bigr)^{3/2}} = \dfrac{\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}}}{\bigl(\frac{y^{2}+x^{2}}{y^{2}}\bigr)^{3/2}} = \dfrac{\frac{r^{2}}{y^{3}}}{\frac{(r^{2})^{3/2}}{y^{3}}} = \dfrac{r^{2}}{r^{3}} = \dfrac{1}{r} \).

Since \( r \) is a constant, \( k \) is constant for all \( x \) in the domain.

\( \boxed{k = \frac{1}{r} \text{ (constant)}} \)

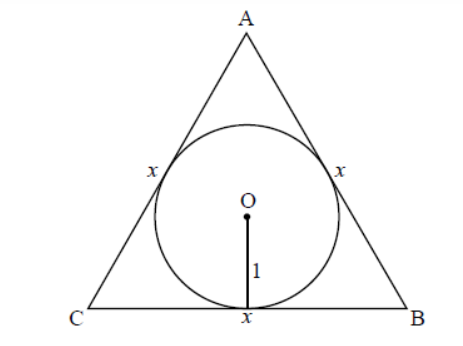

This question investigates regular \( n \)-sided polygons inscribed in and circumscribed about a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit, examining their perimeters as \( n \to \infty \) to approximate \( \pi \). Let \( P_i(n) \) be the perimeter of an inscribed regular \( n \)-gon, and \( P_c(n) \) be the perimeter of a circumscribed regular \( n \)-gon. Consider an equilateral triangle \( ABC \) of side length \( x \) units, circumscribed about a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit with center \( O \).

Let \( P_c(n) \) represent the perimeter of any \( n \)-sided regular polygon circumscribed about a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit.

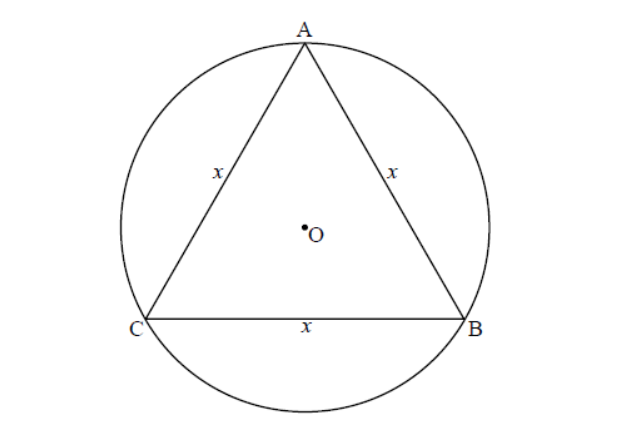

(a) Consider an equilateral triangle \( ABC \) of side length \( x \) units, inscribed in a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit with center \( O \).

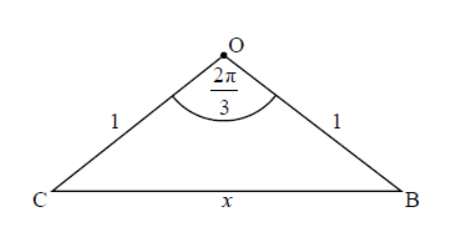

The equilateral triangle \( ABC \) can be divided into three smaller isosceles triangles, each subtending an angle of \( \frac{\text{2}\pi}{\text{3}} \) at \( O \).

Using right-angled trigonometry or otherwise, show that the perimeter of the equilateral triangle \( ABC \) is equal to \( \text{3} \sqrt{\text{3}} \) units [3].

(b) Consider a square of side length \( x \) units, inscribed in a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit. By dividing the inscribed square into four isosceles triangles, find the exact perimeter [3].

(c) Find the perimeter of a regular hexagon, of side length \( x \) units, inscribed in a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit [2].

(d) Show that \( P_i(n) = \text{2} n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \) [3].

(e) Using a Maclaurin series expansion, find \( \lim_{n \to \infty} P_i(n) \) and interpret this result geometrically [5].

(f) Show that \( P_c(n) = \text{2} n \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \) [4].

(g) By writing \( P_c(n) \) as \( \frac{\text{2} \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right)}{\frac{\text{1}}{n}} \), find \( \lim_{n \to \infty} P_c(n) \) [2].

(h) Using results from (d) and (f), determine an inequality for \( \pi \) in terms of \( n \) [2].

(i) Determine the least \( n \) such that the lower and upper bound approximations for \( \pi \) from (h) are within \( \text{0.005} \) of \( \pi \) [3].

▶️ Answer/Explanation

Note: All polygons are regular with side length \( x \), centered at \( O \), in a circle of radius \( \text{1} \) unit. Use \( \pi \approx \text{3.1415926535} \), and numerical answers are exact or rounded to \( \text{3} \) significant figures unless specified.

(a)

Consider triangle \( OCX \), right-angled at \( X \), where \( CX = \frac{x}{\text{2}} \), radius \( OC = \text{1} \), and angle at \( O = \frac{\pi}{\text{3}} \) (see third diagram).

Apply sine: \[ \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{\text{3}} \right) = \frac{\frac{x}{\text{2}}}{\text{1}} \] (M1).

\[ \frac{x}{\text{2}} = \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{\text{3}} \right) = \frac{\sqrt{\text{3}}}{\text{2}} \implies x = \text{2} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{\text{3}}}{\text{2}} = \sqrt{\text{3}} \] (A1).

Perimeter: \[ P_i(\text{3}) = \text{3} \cdot x = \text{3} \sqrt{\text{3}} \] (A1).

Alternative: In triangle \( OAB \), use cosine rule: \[ x^2 = \text{1}^2 + \text{1}^2 – \text{2} \cdot \text{1} \cdot \text{1} \cdot \cos \left( \frac{\text{2}\pi}{\text{3}} \right) = \text{1} + \text{1} – \text{2} \cdot \left( -\frac{\text{1}}{\text{2}} \right) = \text{3} \implies x = \sqrt{\text{3}} \] (M1)(A1).

[3 marks]

(b)

Divide the square into four isosceles triangles, each subtending \( \frac{\text{2}\pi}{\text{4}} = \frac{\pi}{\text{2}} \) at \( O \). In right-angled triangle \( OCX \), \( CX = \frac{x}{\text{2}} \), radius \( OC = \text{1} \), angle at \( O = \frac{\pi}{\text{4}} \):

\[ \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{\text{4}} \right) = \frac{\frac{x}{\text{2}}}{\text{1}} \implies \frac{x}{\text{2}} = \frac{\sqrt{\text{2}}}{\text{2}} \] (M1).

\[ x = \text{2} \cdot \frac{\sqrt{\text{2}}}{\text{2}} = \sqrt{\text{2}} \] (A1).

Perimeter: \[ P_i(\text{4}) = \text{4} \cdot \sqrt{\text{2}} \] (A1).

[3 marks]

(c)

A regular hexagon inscribed in the circle forms \( \text{6} \) equilateral triangles. Each triangle has vertices at \( O \) and two adjacent hexagon vertices, with radius \( OC = \text{1} \) equal to side length \( x = \text{1} \) (A1).

Perimeter: \[ P_i(\text{6}) = \text{6} \cdot \text{1} = \text{6} \] (A1).

[2 marks]

(d)

For an \( n \)-gon, divide into \( n \) isosceles triangles, each subtending \( \frac{\text{2}\pi}{n} \) at \( O \). In right-angled triangle \( OCX \), angle at \( O = \frac{\pi}{n} \), \( CX = \frac{x}{\text{2}} \), radius \( OC = \text{1} \):

\[ \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \frac{\frac{x}{\text{2}}}{\text{1}} \implies \frac{x}{\text{2}} = \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \implies x = \text{2} \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (M1)(A1).

Perimeter: \[ P_i(n) = n \cdot x = \text{2} n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (A1).

[3 marks]

(e)

Find: \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} P_i(n) = \lim_{n \to \infty} \text{2} n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \].

Use Maclaurin series for sine: \[ \sin x = x – \frac{x^3}{\text{6}} + \frac{x^5}{\text{120}} – \cdots \] for small \( x \) (M1).

Let \( x = \frac{\pi}{n} \): \[ \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \frac{\pi}{n} – \frac{\left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right)^3}{\text{6}} + \frac{\left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right)^5}{\text{120}} – \cdots \] (A1).

\[ \text{2} n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \text{2} n \left( \frac{\pi}{n} – \frac{\pi^3}{\text{6} n^3} + \frac{\pi^5}{\text{120} n^5} – \cdots \right) = \text{2} \pi – \frac{\pi^3}{\text{3} n^2} + \frac{\pi^5}{\text{60} n^4} – \cdots \] (A1).

As \( n \to \infty \), higher-order terms vanish: \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \left( \text{2} \pi – \frac{\pi^3}{\text{3} n^2} + \cdots \right) = \text{2} \pi \] (A1).

Geometrically, as \( n \to \infty \), the inscribed \( n \)-gon’s vertices approach the circle’s circumference, yielding the circle’s perimeter \( \text{2} \pi \cdot \text{1} = \text{2} \pi \) (R1).

[5 marks]

(f)

For a circumscribed \( n \)-gon (see first diagram), divide into \( \text{2} n \) right-angled triangles, each with angle \( \frac{\pi}{n} \) at \( O \), opposite side \( \frac{x}{\text{2}} \), adjacent side (radius) \( \text{1} \):

\[ \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \frac{\frac{x}{\text{2}}}{\text{1}} \implies \frac{x}{\text{2}} = \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \implies x = \text{2} \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (M1)(A1).

Perimeter: \[ P_c(n) = n \cdot x = n \cdot \text{2} \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \text{2} n \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (A1)(A1).

[4 marks]

(g)

Rewrite: \[ P_c(n) = \text{2} n \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \frac{\text{2} \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right)}{\frac{\text{1}}{n}} \].

Evaluate: \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{\text{2} \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right)}{\frac{\text{1}}{n}} \]. As \( n \to \infty \), \( \frac{\pi}{n} \to \text{0} \), yielding \( \frac{\text{0}}{\text{0}} \). Apply L’Hôpital’s rule (M1):

Numerator derivative: \[ \text{2} \sec^2 \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \cdot \left( -\frac{\pi}{n^2} \right) \].

Denominator derivative: \[ -\frac{\text{1}}{n^2} \].

\[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{\text{2} \sec^2 \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \cdot \left( -\frac{\pi}{n^2} \right)}{-\frac{\text{1}}{n^2}} = \text{2} \pi \cdot \lim_{n \to \infty} \sec^2 \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) = \text{2} \pi \cdot \text{1} = \text{2} \pi \] (A1).

[2 marks]

(h)

The inscribed \( n \)-gon’s perimeter is less than the circle’s (\( \text{2} \pi \)), and the circumscribed \( n \)-gon’s is greater:

\[ P_i(n) < \text{2} \pi < P_c(n) \implies \text{2} n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) < \text{2} \pi < \text{2} n \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (M1).

Divide by \( \text{2} \): \[ n \sin \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) < \pi < n \tan \left( \frac{\pi}{n} \right) \] (A1).

[2 marks]

(i)

Find the least \( n \) such that the bounds from (h), \( n \sin(\pi/n) < \pi < n \tan(\pi/n) \), are within \( \text{0.005} \) of \( \pi \):

- Conditions: \( |\pi – n \sin(\pi/n)| < \text{0.005} \), \( |n \tan(\pi/n) – \pi| < \text{0.005} \).

- Approximate for large \( n \): Use Maclaurin series, \( \sin(\pi/n) \approx \pi/n – \pi^3/(\text{6} n^3) \).

Then, \( n \sin(\pi/n) \approx \pi – \pi^3/(\text{6} n^2) \), so \( \pi – n \sin(\pi/n) \approx \pi^3/(\text{6} n^2) \).

Require: \( \pi^3/(\text{6} n^2) < \text{0.005} \).

With \( \pi^3 \approx \text{31.00627668} \), compute: \( \text{31.00627668}/(\text{6} \cdot \text{0.005}) \approx \text{1033.542556} \).

Thus, \( n^2 > \text{1033.542556} \), so \( n > \sqrt{\text{1033.542556}} \approx \text{32.148} \) (M1). - Upper bound: Use \( \tan(\pi/n) \approx \pi/n + \pi^3/(\text{3} n^3) \).

Then, \( n \tan(\pi/n) \approx \pi + \pi^3/(\text{3} n^2) \), so \( n \tan(\pi/n) – \pi \approx \pi^3/(\text{3} n^2) \).

Require: \( \pi^3/(\text{3} n^2) < \text{0.005} \).

Compute: \( \text{31.00627668}/(\text{3} \cdot \text{0.005}) \approx \text{2067.085112} \).

Thus, \( n^2 > \text{2067.085112} \), so \( n > \sqrt{\text{2067.085112}} \approx \text{45.466} \). - Least \( n =46\)