Quantization of angular momentum IB DP Physics Study Notes - 2025 Syllabus

Quantization of angular momentum IB DP Physics Study Notes

Quantization of angular momentum IB DP Physics Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on IB Physics syllabus with Students should understand

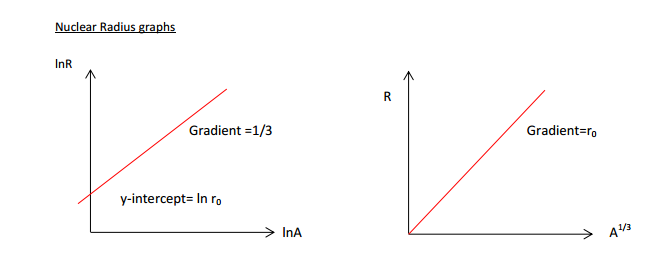

the relationship between the radius and the nucleon number for a nucleus as given by R = R0A1/3 and implications for nuclear densities

deviations from Rutherford scattering at high energies

the distance of closest approach in head-on scattering experiments

the discrete energy levels in the Bohr model for hydrogen as given by $E = − \frac{13 . 6}{ n^2} eV$

that the existence of quantized energy and orbits arise from the quantization of angular momentum in the Bohr model for hydrogen as given by $mvr =\frac{ nh }{2π}$ .

Standard level and higher level: 6 hours

Additional higher level: 3 hours

- IB DP Physics 2025 SL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 1

- IB DP Physics 2025 HL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 1

- IB DP Physics 2025 SL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 2

- IB DP Physics 2025 HL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 2

Nuclear Radius and Nucleon Number

Experimental evidence shows that the radius \( R \) of a nucleus depends on its nucleon number \( A \).

The relationship is given by:

![]()

Where:

- \( R \): Radius of the nucleus (in meters)

- \( R_0 \): Constant \( \approx 1.2 \times 10^{-15} \, \text{m} \)

- \( A \): Nucleon (mass) number

Physical meaning:

Since the radius is proportional to \( A^{1/3} \), the volume of the nucleus is proportional to \( A \).

This implies that each nucleon occupies approximately the same volume, regardless of the size of the nucleus.

Implications for nuclear density:

Nuclear density is defined as mass per unit volume.

Since nuclear mass \( \propto A \) and nuclear volume \( \propto A \), the density of all nuclei is approximately constant.

This means light and heavy nuclei have nearly the same nuclear density.

IB exam points:

- State that nuclear radius increases with nucleon number.

- Explain that volume is proportional to \( A \).

- Conclude that nuclear density is approximately constant.

Example:

Estimate the radius of a nucleus with nucleon number \( A = 64 \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Use the nuclear radius formula

\( R = R_0 A^{1/3} \)

Step 2: Substitute values

\( R = (1.2 \times 10^{-15})(64)^{1/3} \)

Step 3: Calculate

\( (64)^{1/3} = 4 \)

\( R = 4.8 \times 10^{-15} \, \text{m} \)

Interpretation:

This value is consistent with typical nuclear dimensions and supports the idea of constant nuclear density.

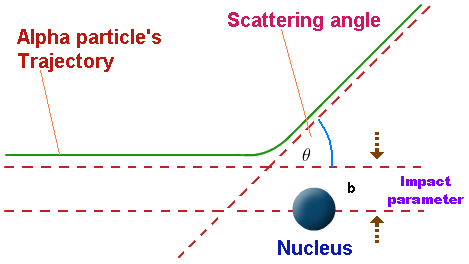

Deviations from Rutherford Scattering at High Energies

Rutherford scattering theory assumes that alpha particles interact only through electrostatic (Coulomb) repulsion with the positively charged nucleus.

At relatively low alpha-particle energies, experimental results closely follow the predictions of Rutherford scattering.

However, at high energies, clear deviations from Rutherford scattering are observed.

Observed deviations:

- More large-angle scattering occurs than predicted.

- Some alpha particles approach much closer to the nucleus.

- Scattering no longer follows the inverse-square Coulomb prediction.

Reasons for the deviations:

- At high energies, alpha particles penetrate deep into the nuclear region.

- The strong nuclear force, which is attractive and short-ranged, becomes significant.

- Rutherford scattering does not account for nuclear forces or the finite size of the nucleus.

Implications:

These deviations provide experimental evidence that the nucleus is not a point charge and that forces other than electrostatic repulsion act at very small distances.

They also support the existence of the strong nuclear force and the finite size of the nucleus.

IB exam points:

- State that deviations occur at high alpha-particle energies.

- Explain that nuclear forces become important at short distances.

- Mention finite nuclear size as a cause.

Example:

Explain why Rutherford scattering theory fails for very high-energy alpha particles.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

At high energies, alpha particles approach very close to the nucleus.

At these short distances, the strong nuclear force becomes significant and alters the scattering pattern.

Since Rutherford scattering only considers electrostatic repulsion and treats the nucleus as a point charge, its predictions no longer hold.

Distance of Closest Approach in Head-On Scattering Experiments

In a head-on Rutherford scattering experiment, an alpha particle is directed straight towards a nucleus.

As both the alpha particle and the nucleus are positively charged, a strong electrostatic repulsion acts between them.

As the alpha particle approaches the nucleus, its kinetic energy is converted into electric potential energy.

At the point of closest approach, the alpha particle momentarily comes to rest before reversing direction.

Energy consideration:

Assuming the alpha particle starts far from the nucleus, its initial electric potential energy is zero.

\( E_{K0} = E_P \)

At the distance of closest approach \( R_0 \), all kinetic energy has been converted into electric potential energy:

\( E_{K0} = \dfrac{kQq}{R_0} \)

For an alpha particle \( (q = +2e) \) approaching a nucleus of charge \( +Ze \):

\( E_{K0} = \dfrac{2Zke^2}{R_0} \)

This equation can be rearranged to calculate the distance of closest approach.

Physical significance:

- The distance of closest approach provides an estimate of nuclear size.

- It represents the minimum distance the alpha particle can reach using electrostatic repulsion alone.

- At very small distances, deviations indicate the influence of nuclear forces.

IB exam points:

- Use conservation of energy.

- State that kinetic energy becomes zero at closest approach.

- Assume initial potential energy is zero at infinity.

Example:

An alpha particle with kinetic energy \( 8.0 \times 10^{-13} \, \text{J} \) is fired directly at a gold nucleus (\( Z = 79 \)). Calculate the distance of closest approach.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Use the closest-approach formula

\( E_{K0} = \dfrac{2Zke^2}{R_0} \)

Step 2: Rearrange

\( R_0 = \dfrac{2Zke^2}{E_{K0}} \)

Step 3: Substitute values

\( R_0 = \dfrac{2(79)(9.0 \times 10^9)(1.60 \times 10^{-19})^2}{8.0 \times 10^{-13}} \)

Step 4: Calculate

\( R_0 \approx 4.6 \times 10^{-14} \, \text{m} \)

Interpretation:

This distance is greater than the nuclear radius, showing that electrostatic repulsion prevents closer approach.

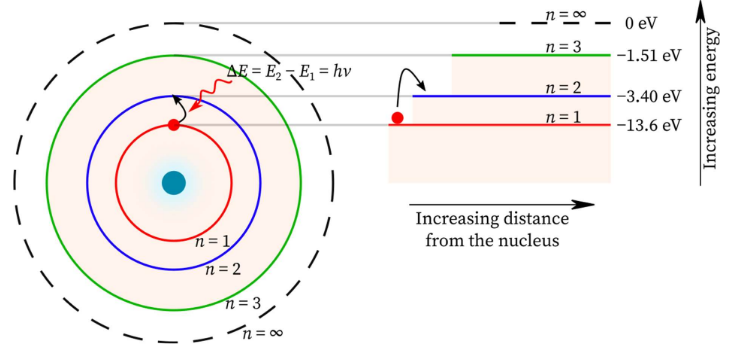

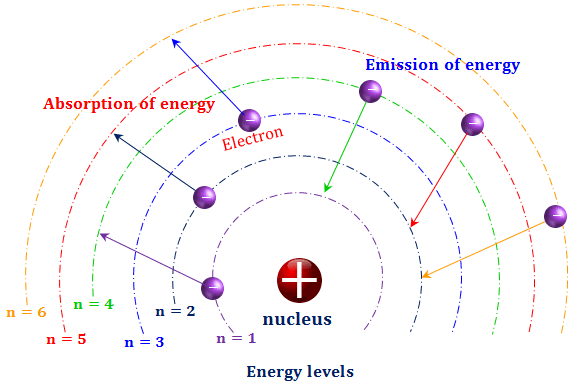

Discrete Energy Levels in the Bohr Model for Hydrogen

The Bohr model of the hydrogen atom proposes that an electron can only occupy certain allowed circular orbits around the nucleus.

Each allowed orbit corresponds to a specific, fixed energy level. These energy levels are discrete (quantised).

The energy of an electron in the hydrogen atom is given by:

\( E = – \dfrac{13.6}{n^2} \, \text{eV} \)

Where:

- \( E \): Energy of the electron (in electronvolts)

- \( n \): Principal quantum number \( (n = 1, 2, 3, \dots) \)

Key features of the energy levels:

- The energy levels are negative, indicating the electron is bound to the nucleus.

- The lowest energy level \( (n = 1) \) is called the ground state.

- As \( n \) increases, the energy levels become closer together.

- At \( n \to \infty \), \( E \to 0 \), corresponding to ionisation of the atom.

Physical significance:

Electrons can move between energy levels only by absorbing or emitting photons with energy equal to the difference between the levels.

This explains the discrete emission and absorption spectra observed for hydrogen.

IB exam points:

- State that energy levels are quantised.

- Use the correct formula for hydrogen energy levels.

- Explain the meaning of the negative sign.

Example:

Calculate the energy of an electron in the hydrogen atom when it is in the \( n = 3 \) energy level.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Use the Bohr energy formula

\( E = – \dfrac{13.6}{n^2} \, \text{eV} \)

Step 2: Substitute \( n = 3 \)

\( E = – \dfrac{13.6}{9} = -1.51 \, \text{eV} \)

Interpretation:

The electron is still bound to the nucleus but has higher energy than in the ground state.

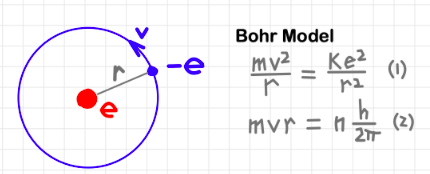

Quantisation of Angular Momentum in the Bohr Model for Hydrogen

In the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom, electrons are allowed to move only in certain stable circular orbits around the nucleus.

Bohr proposed that these allowed orbits arise because the angular momentum of the electron is quantised.

The condition for allowed orbits is:

\( m v r = \dfrac{n h}{2\pi} \)

Where:

- \( m \): Mass of the electron

- \( v \): Speed of the electron in the orbit

- \( r \): Radius of the orbit

- \( h \): Planck constant

- \( n \): Principal quantum number \( (n = 1, 2, 3, \dots) \)

Key implication:

Only orbits for which the electron’s angular momentum satisfies this condition are permitted.

As a result, the electron can occupy only specific radii and specific energies, leading to quantised energy levels.

Connection to atomic spectra:

When an electron transitions between these allowed orbits, a photon is emitted or absorbed with energy equal to the difference between the energy levels.

This explains why hydrogen produces discrete emission and absorption spectra.

IB exam points:

- State that angular momentum is quantised.

- Quote the correct angular momentum condition.

- Link quantised angular momentum to discrete orbits and energy levels.

Example:

Explain why electrons in the Bohr model cannot exist in arbitrary orbits.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

In the Bohr model, an electron’s angular momentum must satisfy \( m v r = \dfrac{n h}{2\pi} \).

Only specific values of \( r \) and \( v \) meet this condition.

Therefore, only certain orbits and corresponding energy levels are allowed, leading to quantised atomic structure.