Radioactivity IB DP Physics Study Notes - 2025 Syllabus

Radioactivity IB DP Physics Study Notes

Radioactivity IB DP Physics Study Notes at IITian Academy focus on specific topic and type of questions asked in actual exam. Study Notes focus on IB Physics syllabus with Students should understand

- the evidence for the strong nuclear force

- the role of the ratio of neutrons to protons for the stability of nuclides

- the approximate constancy of binding energy curve above a nucleon number of 60

- that the spectrum of alpha and gamma radiations provides evidence for discrete nuclear energy levels

- the continuous spectrum of beta decay as evidence for the neutrino

- the decay constant λ and the radioactive decay law as given by N = N0e−λt

- that the decay constant approximates the probability of decay in unit time only in the limit of sufficiently small λt

- the activity as the rate of decay as given by A = λN = λN0e−λt the relationship between half-life and the decay constant as given by $T_{\frac{1}{2}} =\frac{ ln2}{λ} $.

Standard level and higher level: 7 hours

Additional higher level: 5 hours

- IB DP Physics 2025 SL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 1

- IB DP Physics 2025 HL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 1

- IB DP Physics 2025 SL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 2

- IB DP Physics 2025 HL- IB Style Practice Questions with Answer-Topic Wise-Paper 2

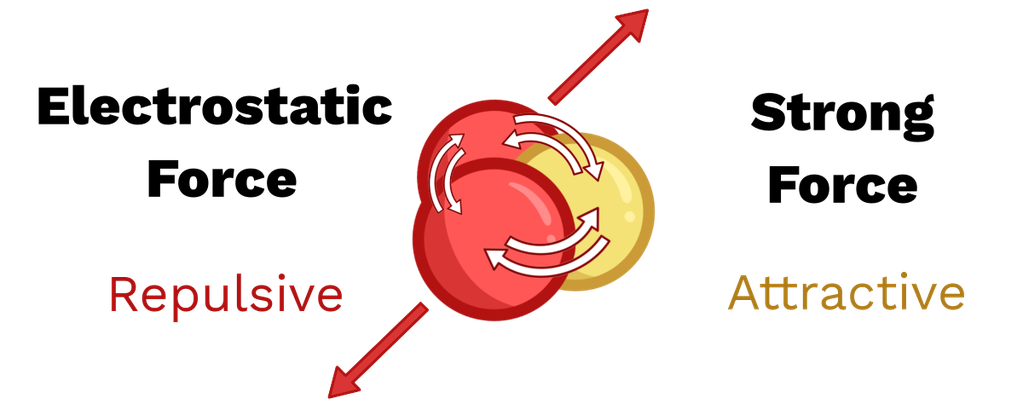

Evidence for the Strong Nuclear Force

Protons within the atomic nucleus all carry positive charge and therefore experience strong electrostatic repulsion.

Despite this repulsion, nuclei (except very light ones) are stable. This provides evidence for another force acting within the nucleus.

This force is known as the strong nuclear force.

Key experimental evidence:

- Stable nuclei exist even though electrostatic repulsion between protons is very large.

- Rutherford scattering experiments at high energies show deviations from purely Coulomb (electrostatic) predictions.

- The distance of closest approach in alpha-particle scattering indicates an additional attractive force at very small distances.

Properties inferred from evidence:

- The strong nuclear force is much stronger than electrostatic repulsion at short distances.

- It is a short-range force, effective only over distances of about \( 10^{-15} \, \text{m} \).

- It is attractive between nucleons (protons and neutrons).

Role of neutrons:

Neutrons contribute to nuclear stability by providing attractive strong nuclear force without adding electrostatic repulsion.

This explains why heavier nuclei require more neutrons than protons to remain stable.

Example:

Explain why the existence of stable nuclei provides evidence for the strong nuclear force.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Protons in the nucleus repel each other due to electrostatic forces.

The fact that nuclei remain stable shows that an additional attractive force must overcome this repulsion.

This force is the strong nuclear force, which acts at very short distances and binds nucleons together.

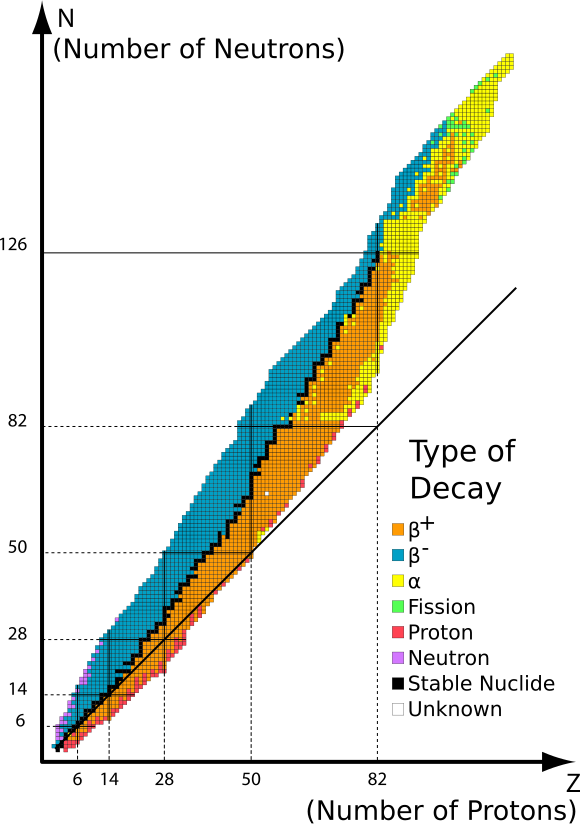

Neutron–Proton Ratio and the Stability of Nuclides

The stability of a nucleus depends strongly on the ratio of neutrons to protons (\( N:Z \)).

Protons repel each other due to electrostatic forces, while both protons and neutrons experience the strong nuclear force.

Neutrons play a crucial role by increasing the attractive strong nuclear force without increasing electrostatic repulsion.

Trends in nuclear stability:

- For light nuclei, stability is greatest when \( N \approx Z \).

- As proton number increases, additional neutrons are required to maintain stability.

- Heavy stable nuclei have \( N > Z \).

Consequences of an incorrect neutron–proton ratio:

- Too many neutrons → nucleus tends to undergo beta-minus decay.

- Too many protons → nucleus tends to undergo beta-plus decay or electron capture.

Physical explanation:

As nuclei become larger, electrostatic repulsion between protons increases.

Additional neutrons increase the binding provided by the strong nuclear force, helping to stabilise the nucleus.

IB exam points:

- State that neutrons contribute to stability without increasing repulsion.

- Explain why heavy nuclei require more neutrons.

- Link instability to beta decay.

Example:

Explain why heavy nuclei contain more neutrons than protons.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

As proton number increases, electrostatic repulsion between protons becomes stronger.

Neutrons add attractive strong nuclear force without increasing repulsion.

Therefore, heavy nuclei require more neutrons than protons to remain stable.

Approximate Constancy of Binding Energy per Nucleon for \( A > 60 \)

The binding energy per nucleon is the average energy required to remove a nucleon from the nucleus.

When binding energy per nucleon is plotted against nucleon number \( A \), a characteristic curve is obtained.

For nuclei with \( A \gtrsim 60 \), the binding energy per nucleon becomes approximately constant.

Physical explanation:

The strong nuclear force is a short-range force and each nucleon interacts strongly only with its nearest neighbours.

As the nucleus becomes larger, each nucleon does not interact with all other nucleons, but only with nearby ones.

Therefore, adding more nucleons does not significantly increase the average binding per nucleon.

Implications:

- Large nuclei are not significantly more tightly bound per nucleon than medium-sized nuclei.

- This explains why binding energy per nucleon reaches a plateau.

- It supports the idea that nuclear forces are short-ranged and saturating.

IB exam points:

- State that binding energy per nucleon is approximately constant for \( A > 60 \).

- Link this to short-range nature of the strong force.

- Mention nearest-neighbour interactions.

Example:

Explain why the binding energy per nucleon does not increase significantly for very heavy nuclei.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

The strong nuclear force is short-ranged, so each nucleon only interacts with nearby nucleons.

As more nucleons are added, they do not significantly increase the number of strong interactions per nucleon.

Therefore, the average binding energy per nucleon remains approximately constant for large nuclei.

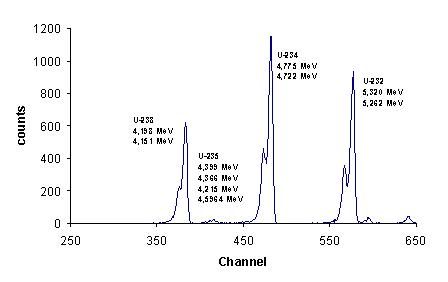

Alpha and Gamma Radiation Spectra and Discrete Nuclear Energy Levels

The nucleus, like the atom, can exist only in discrete (quantised) energy states.

Evidence for these discrete nuclear energy levels comes from the spectra of alpha and gamma radiation.

Alpha radiation spectra:

Alpha particles emitted from a radioactive nucleus do not have a continuous range of energies.

Instead, alpha radiation consists of discrete energy lines, each corresponding to a specific nuclear transition.

This shows that alpha decay occurs between well-defined nuclear energy levels.

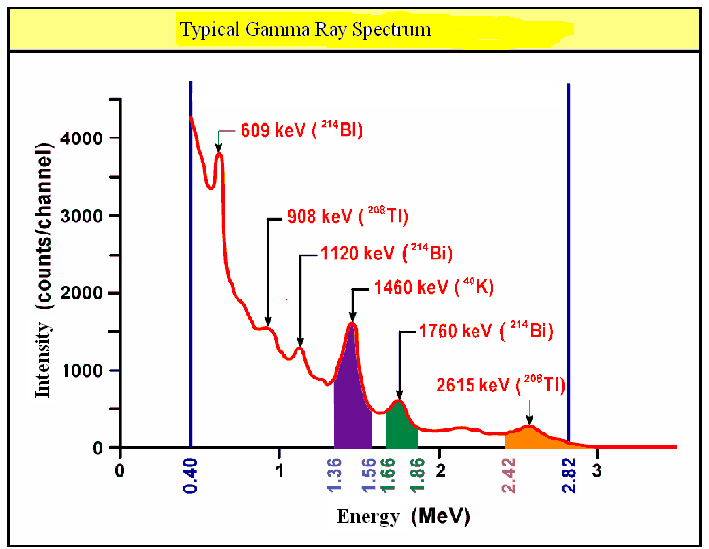

Gamma radiation spectra:

After alpha or beta decay, the daughter nucleus is often left in an excited state.

The nucleus then emits gamma photons as it transitions to a lower energy state.

Gamma radiation also appears as discrete lines in a spectrum, indicating fixed energy differences between nuclear levels.

Key conclusion:

The discrete energies observed in alpha and gamma spectra provide direct evidence that nuclear energy levels are quantised.

IB exam points:

- State that alpha and gamma spectra are line spectra.

- Explain that each line corresponds to a nuclear transition.

- Conclude that nuclear energy levels are discrete.

Example:

Explain why the observation of discrete gamma-ray energies supports the idea of quantised nuclear energy levels.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Gamma rays are emitted when a nucleus transitions between energy states.

The fact that only specific gamma-ray energies are observed shows that only certain energy differences are allowed.

This demonstrates that nuclear energy levels are quantised.

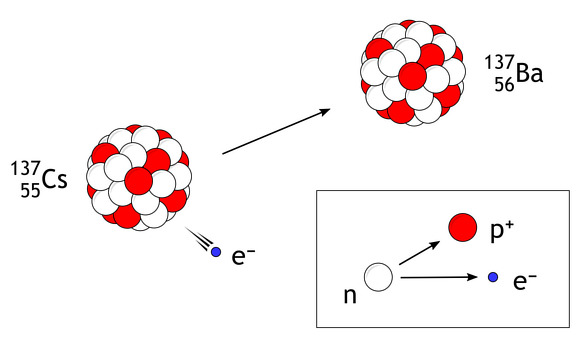

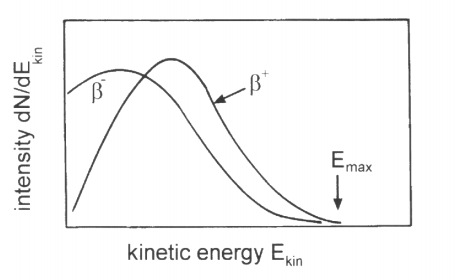

Continuous Beta-Decay Spectrum and Evidence for the Neutrino

In beta decay, an unstable nucleus emits a beta particle (electron or positron).

Unlike alpha and gamma radiation, the kinetic energy of beta particles is observed to form a continuous spectrum rather than discrete lines.

Key experimental observation:

Beta particles are emitted with a wide range of energies, from near zero up to a maximum value.

This contradicts the expectation of discrete energies if only two particles were involved in the decay.

Problem with early interpretation:

If beta decay involved only the nucleus and the beta particle, energy and momentum would not be conserved.

The “missing” energy varied from event to event.

Pauli’s solution:

To explain this, Wolfgang Pauli proposed the existence of a third particle the neutrino.

The neutrino carries away some of the energy and momentum in each decay.

This explains why the beta particle emerges with a range of kinetic energies.

Modern beta-decay description:

\( n \rightarrow p + e^- + \bar{\nu} \)

Energy and momentum are conserved when the neutrino is included.

Key conclusion:

The continuous beta spectrum provides strong evidence for the existence of the neutrino.

IB exam points:

- State that beta spectra are continuous.

- Explain that energy appears to be missing.

- Introduce the neutrino to conserve energy and momentum.

Example:

Explain why the continuous energy spectrum of beta particles implies the existence of a neutrino.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

If only the beta particle and nucleus were involved, beta particles would have fixed energies.

The observed continuous spectrum shows that some energy is carried away by another particle.

The neutrino accounts for the missing energy and momentum, conserving physical laws.

Decay Constant \( \lambda \) and the Radioactive Decay Law

Radioactive decay is a random process in which unstable nuclei transform into more stable nuclei.

The probability that a nucleus will decay per unit time is characterised by the decay constant \( \lambda \).

The number of undecayed nuclei decreases exponentially with time according to the radioactive decay law:

\( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \)

Where:

- \( N \): Number of undecayed nuclei at time \( t \)

- \( N_0 \): Initial number of nuclei

- \( \lambda \): Decay constant (in s\(^{-1}\))

- \( t \): Time elapsed

Meaning of the decay constant:

The decay constant represents the fraction of nuclei that decay per unit time.

A larger value of \( \lambda \) indicates a faster rate of decay.

Key features of radioactive decay:

- Decay of individual nuclei is unpredictable.

- The decay law applies statistically to a large number of nuclei.

- The decay constant is independent of external conditions.

IB exam points:

- State that radioactive decay is random.

- Quote the exponential decay equation correctly.

- Explain the physical meaning of the decay constant.

Example:

A radioactive sample initially contains \( 8.0 \times 10^6 \) nuclei. The decay constant is \( 2.0 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{s}^{-1} \). Calculate the number of undecayed nuclei after \( 500 \, \text{s} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Write the decay equation

\( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \)

Step 2: Substitute values

\( N = (8.0 \times 10^6)e^{-(2.0 \times 10^{-3})(500)} \)

Step 3: Calculate

\( N = 8.0 \times 10^6 e^{-1.0} \approx 2.94 \times 10^6 \)

Interpretation:

About 37% of the original nuclei remain undecayed after 500 seconds.

Decay Constant as a Probability of Decay in Unit Time

The decay constant \( \lambda \) is often interpreted as the probability per unit time that a given nucleus will decay.

This interpretation is only valid in the limit where the time interval considered is very small.

Radioactive decay law:

\( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \)

The fraction of nuclei that decay in time \( t \) is:

\( \dfrac{\Delta N}{N_0} = 1 – e^{-\lambda t} \)

Small-time approximation:

For sufficiently small values of \( \lambda t \), the exponential can be approximated using:

\( e^{-\lambda t} \approx 1 – \lambda t \)

Substituting gives:

\( \dfrac{\Delta N}{N_0} \approx \lambda t \)

Hence, when \( \lambda t \ll 1 \), the decay constant \( \lambda \) represents the probability of decay per unit time.

Important limitation:

For larger values of \( \lambda t \), radioactive decay must be treated using the full exponential law, and \( \lambda \) can no longer be interpreted directly as a simple probability.

IB exam points:

- State that \( \lambda \) is a probability per unit time only for small \( \lambda t \).

- Use the approximation \( e^{-\lambda t} \approx 1 – \lambda t \).

- Emphasise the statistical nature of decay.

Example:

A radioactive nuclide has a decay constant \( \lambda = 5.0 \times 10^{-4} \, \text{s}^{-1} \). Estimate the probability that a nucleus decays in a time interval of \( 10 \, \text{s} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

First calculate \( \lambda t \):

\( \lambda t = (5.0 \times 10^{-4})(10) = 5.0 \times 10^{-3} \ll 1 \)

Since \( \lambda t \) is very small, the probability of decay is approximately:

\( P \approx \lambda t = 5.0 \times 10^{-3} \)

This corresponds to a \( 0.5\% \) chance of decay in 10 seconds.

Activity as the Rate of Radioactive Decay

The activity of a radioactive sample is defined as the rate at which nuclei decay. ![]()

It represents the number of decays occurring per unit time.

Activity is given by:

\( A = \lambda N \)

Using the radioactive decay law \( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \), the activity at time \( t \) can be written as:

\( A = \lambda N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \)

Where:![]()

- \( A \): Activity of the sample (in becquerels, Bq)

- \( \lambda \): Decay constant (in s\(^{-1}\))

- \( N \): Number of undecayed nuclei at time \( t \)

- \( N_0 \): Initial number of nuclei

Unit of activity:

The SI unit of activity is the becquerel (Bq), where:

![]()

Key features:

- Activity decreases exponentially with time.

- Activity depends on both the number of undecayed nuclei and the decay constant.

- A larger decay constant gives a higher activity for the same number of nuclei.

IB exam points:

- Define activity as decay rate.

- Quote the equation \( A = \lambda N \).

- State the SI unit as the becquerel.

Example:

A radioactive sample contains \( 4.0 \times 10^6 \) undecayed nuclei and has a decay constant of \( 1.5 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{s}^{-1} \). Calculate the activity of the sample.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Use the activity equation

\( A = \lambda N \)

Step 2: Substitute values

\( A = (1.5 \times 10^{-3})(4.0 \times 10^6) \)

Step 3: Calculate

\( A = 6.0 \times 10^3 \, \text{Bq} \)

Interpretation:

The sample undergoes 6000 nuclear decays per second.

Relationship Between Half-Life and the Decay Constant

The half-life \( T_{1/2} \) of a radioactive substance is the time taken for the number of undecayed nuclei (or the activity) to fall to half of its initial value.

The half-life is related to the decay constant \( \lambda \) by:![]()

\( T_{1/2} = \dfrac{\ln 2}{\lambda} \)

Derivation outline:

Starting from the radioactive decay law:

\( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \)

At half-life, \( N = \dfrac{N_0}{2} \):

\( \dfrac{1}{2} = e^{-\lambda T_{1/2}} \)

Taking natural logarithms gives:

\( \lambda T_{1/2} = \ln 2 \)

Hence:

\( T_{1/2} = \dfrac{\ln 2}{\lambda} \)

Physical meaning:

- A larger decay constant corresponds to a shorter half-life.

- Half-life is independent of the initial number of nuclei.

- Half-life is a characteristic property of a radioactive nuclide.

IB exam points:

- Quote the correct relationship between \( T_{1/2} \) and \( \lambda \).

- Explain that half-life does not depend on sample size.

- Link short half-life to large decay constant.

Example:

A radioactive nuclide has a decay constant of \( \lambda = 4.0 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{s}^{-1} \). Calculate its half-life.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Use the half-life equation

\( T_{1/2} = \dfrac{\ln 2}{\lambda} \)

Step 2: Substitute values

\( T_{1/2} = \dfrac{0.693}{4.0 \times 10^{-3}} \)

Step 3: Calculate

\( T_{1/2} \approx 173 \, \text{s} \)

Interpretation:

The number of undecayed nuclei halves every 173 seconds.

IB Physics Radioactivity Exam Style Worked Out Questions

Question

When alpha particle scattering experiments were carried out with high-energy alpha particles, deviations from Rutherford scattering were observed. What was deduced as a result of this observation?

A. The size of the alpha particle

B. The size of the nucleus

C. The nature of the electrostatic field inside the nucleus

D. The nature of the weak nuclear force within the nucleus

▶️Answer/Explanation

Ans B

Question

Radioactive nuclide $\mathrm{X}$ decays into a stable nuclide $\mathrm{Y}$. The decay constant of $\mathrm{X}$ is $\lambda$. The variation with time $t$ of number of nuclei of $X$ and $Y$ are shown on the same axes.

What is the expression for $s$ ?

A. $\frac{\ln 2}{\lambda}$

B. $\frac{1}{\lambda}$

C. $\frac{\lambda}{\ln 2}$

D. $\ln 2$

▶️Answer/Explanation

Ans:A