IIT JEE Main Maths -Unit 9- Linear differential equations of type \(\mathrm{\frac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)}\)- Study Notes-New Syllabus

IIT JEE Main Maths -Unit 9- Linear differential equations of type \(\mathrm{\frac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)}\) – Study Notes – New syllabus

IIT JEE Main Maths -Unit 9- Linear differential equations of type \(\mathrm{\frac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)}\) – Study Notes -IIT JEE Main Maths – per latest Syllabus.

Key Concepts:

- Linear Differential Equations of Type \( \displaystyle \frac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) \)

- Differential Equations Reducible to Linear Form (Bernoulli’s Equation)

- Applications of Differential Equations — Growth and Decay, Newton’s Law of Cooling, and Motion Problems

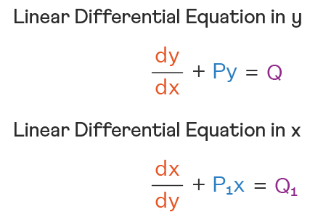

Linear Differential Equations of Type \( \displaystyle \frac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) \)

A linear differential equation is an equation in which the dependent variable \( y \) and its derivative \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} \) appear only to the first power and are not multiplied together.

The standard form is:

$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) $

Here,

- \( P(x) \) and \( Q(x) \) are known functions of \( x \).

- \( y \) is the dependent variable.

Standard Form and Integrating Factor (I.F.)

The equation is said to be in standard form if it can be written as:

$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) $

The Integrating Factor (I.F.)</strong) is defined as:

$ \text{I.F.} = e^{\int P(x)\,dx} $

General Solution

Multiplying both sides of the differential equation by the integrating factor:

$ e^{\int P(x)\,dx} \dfrac{dy}{dx} + e^{\int P(x)\,dx} P(x)y = Q(x)e^{\int P(x)\,dx} $

The left-hand side becomes the derivative of \( y \times \text{I.F.} \):

$ \dfrac{d}{dx}\left[y \cdot e^{\int P(x)\,dx}\right] = Q(x)e^{\int P(x)\,dx} $

Integrating both sides:

$ y \cdot e^{\int P(x)\,dx} = \int Q(x)e^{\int P(x)\,dx}\,dx + C $

Hence, the general solution is:

$ \boxed{y = e^{-\int P(x)\,dx}\left[\int Q(x)e^{\int P(x)\,dx}\,dx + C\right]} $

Steps to Solve

- Write the equation in standard form \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) \).

- Find the integrating factor \( \text{I.F.} = e^{\int P(x)\,dx} \).

- Multiply the entire equation by the I.F.

- Recognize that LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(y \cdot \text{I.F.}) \).

- Integrate both sides and solve for \( y \).

Special Case — When \( Q(x) = 0 \)

The equation reduces to:

$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = 0 $

This is a homogeneous linear differential equation whose solution is:

$ y = Ce^{-\int P(x)\,dx} $

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + y = e^{-x} \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Compare with standard form \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) \).

Here, \( P(x) = 1, \, Q(x) = e^{-x}. \)

Step 2: Find the integrating factor:

\( \text{I.F.} = e^{\int 1\,dx} = e^x. \)

Step 3: Multiply throughout by \( e^x \):

\( e^x\dfrac{dy}{dx} + e^x y = 1. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(y e^x) \). Hence,

\( \dfrac{d}{dx}(y e^x) = 1. \)

Step 4: Integrate both sides:

\( y e^x = x + C. \)

Step 5: Final Solution:

\( \boxed{y = e^{-x}(x + C).} \)

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + 2y = 4x \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Standard form → \( P(x) = 2, \, Q(x) = 4x. \)

Step 2: Integrating Factor:

\( \text{I.F.} = e^{\int 2\,dx} = e^{2x}. \)

Step 3: Multiply the whole equation by \( e^{2x} \):

\( e^{2x}\dfrac{dy}{dx} + 2ye^{2x} = 4xe^{2x}. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(y e^{2x}) \). So,

\( \dfrac{d}{dx}(y e^{2x}) = 4xe^{2x}. \)

Step 4: Integrate both sides:

\( y e^{2x} = \int 4xe^{2x}\,dx. \)

Using integration by parts: \( \int xe^{2x}\,dx = \dfrac{xe^{2x}}{2} – \dfrac{e^{2x}}{4}. \)

\( \Rightarrow y e^{2x} = 4\left(\dfrac{xe^{2x}}{2} – \dfrac{e^{2x}}{4}\right) + C = 2xe^{2x} – e^{2x} + C. \)

Step 5: Divide by \( e^{2x} \):

\( \boxed{y = 2x – 1 + Ce^{-2x}.} \)

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + \dfrac{y}{x} = \sin x \), for \( x > 0 \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Standard form: \( P(x) = \dfrac{1}{x}, \, Q(x) = \sin x. \)

Step 2: Integrating Factor:

\( \text{I.F.} = e^{\int 1/x\,dx} = e^{\ln x} = x. \)

Step 3: Multiply through by \( x \):

\( x\dfrac{dy}{dx} + y = x\sin x. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(xy). \)

\( \dfrac{d}{dx}(xy) = x\sin x. \)

Step 4: Integrate both sides:

\( xy = \int x\sin x\,dx. \)

Integration by parts: \( \int x\sin x\,dx = -x\cos x + \sin x. \)

\( \Rightarrow xy = -x\cos x + \sin x + C. \)

Step 5: Final Solution:

\( \boxed{y = -\cos x + \dfrac{\sin x}{x} + \dfrac{C}{x}.} \)

Differential Equations Reducible to Linear Form (Bernoulli’s Equation)

Some first-order differential equations are not linear in \( y \) but can be converted to a linear form by a suitable substitution. A very important class of such equations is known as Bernoulli’s Equations.

Bernoulli’s Differential Equation — Standard Form

The standard form of Bernoulli’s equation is:

$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)y^n $

where \( n \neq 0, 1 \).

- If \( n = 0 \), it becomes a linear differential equation \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x) \).

- If \( n = 1 \), it becomes a separable equation \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} = Q(x) – P(x)y \).

Method of Solving Bernoulli’s Equation

- Divide both sides by \( y^n \) (to make the right side contain only \( Q(x) \)).

- Make the substitution \( y^{1-n} = z \).

- Differentiate: \( \dfrac{dz}{dx} = (1 – n)y^{-n}\dfrac{dy}{dx} \).

- Substitute this in the given equation to obtain a linear equation in \( z \).

- Solve the resulting linear differential equation using the Integrating Factor (I.F.) method.

Derivation Outline

Starting with \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)y^n \):

Divide by \( y^n \): $ y^{-n}\dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y^{1-n} = Q(x) $

Now put \( y^{1-n} = z \Rightarrow \dfrac{dz}{dx} = (1-n)y^{-n}\dfrac{dy}{dx}. \)

Substitute into the equation:

$ \dfrac{1}{1-n}\dfrac{dz}{dx} + P(x)z = Q(x) $

Multiply both sides by \( 1-n \):

$ \dfrac{dz}{dx} + (1-n)P(x)z = (1-n)Q(x) $

This is a linear equation in \( z \).

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + y = y^2 \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Here, \( P(x) = 1, Q(x) = 1, n = 2. \)

Equation: \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + y = y^2. \)

Step 2: Divide by \( y^2 \): \( y^{-2}\dfrac{dy}{dx} + \dfrac{1}{y} = 1. \)

Step 3: Substitution \( y^{1-n} = y^{-1} = z. \)

\( \dfrac{dz}{dx} = -y^{-2}\dfrac{dy}{dx}. \)

So, \( -\dfrac{dz}{dx} + \dfrac{1}{y} = 1. \)

But \( \dfrac{1}{y} = z. \Rightarrow -\dfrac{dz}{dx} + z = 1. \)

Step 4: Simplify: \( \dfrac{dz}{dx} – z = -1. \)

Step 5: Integrating factor: \( e^{\int -1\,dx} = e^{-x}. \)

Multiply throughout by \( e^{-x} \): \( e^{-x}\dfrac{dz}{dx} – ze^{-x} = -e^{-x}. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(ze^{-x}) \). So, \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(ze^{-x}) = -e^{-x}. \)

\( ze^{-x} = \int -e^{-x}dx = e^{-x} + C. \)

\( z = 1 + Ce^{x}. \)

Step 6: Substitute back \( z = 1/y \): \( \dfrac{1}{y} = 1 + Ce^{x}. \)

Final Answer: \( \boxed{y = \dfrac{1}{1 + Ce^{x}}.} \)

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + \dfrac{2y}{x} = 3xy^2 \), where \( x > 0 \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: Compare with \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} + P(x)y = Q(x)y^n \): \( P(x) = \dfrac{2}{x}, Q(x) = 3x, n = 2. \)

Step 2: Divide by \( y^2 \): \( y^{-2}\dfrac{dy}{dx} + \dfrac{2y^{-1}}{x} = 3x. \)

Step 3: Put \( y^{-1} = z \Rightarrow \dfrac{dz}{dx} = -y^{-2}\dfrac{dy}{dx}. \)

Substitute: \( -\dfrac{dz}{dx} + \dfrac{2z}{x} = 3x. \)

\( \Rightarrow \dfrac{dz}{dx} – \dfrac{2z}{x} = -3x. \)

Step 4: Integrating Factor: \( \text{I.F.} = e^{\int -\frac{2}{x}dx} = e^{-2\ln x} = x^{-2}. \)

Step 5: Multiply through by \( x^{-2} \): \( x^{-2}\dfrac{dz}{dx} – \dfrac{2z}{x^3} = -3. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(z x^{-2}) \). Hence, \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(z x^{-2}) = -3. \)

Integrate both sides: \( z x^{-2} = -3x + C. \)

\( z = -3x^3 + Cx^2. \)

Step 6: Substitute \( z = \dfrac{1}{y} \): \( \boxed{\dfrac{1}{y} = -3x^3 + Cx^2.} \)

Example

Solve \( \dfrac{dy}{dx} – \dfrac{y}{x} = x^2y^3 \).

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Step 1: \( P(x) = -\dfrac{1}{x}, \, Q(x) = x^2, \, n = 3. \)

Step 2: Divide both sides by \( y^3 \): \( y^{-3}\dfrac{dy}{dx} – \dfrac{y^{-2}}{x} = x^2. \)

Step 3: Let \( y^{1-n} = y^{-2} = z \Rightarrow \dfrac{dz}{dx} = -2y^{-3}\dfrac{dy}{dx}. \)

Substitute into equation:

\( -\dfrac{1}{2}\dfrac{dz}{dx} – \dfrac{z}{x} = x^2. \)

Multiply both sides by \( -2 \): \( \dfrac{dz}{dx} + \dfrac{2z}{x} = -2x^2. \)

Step 4: I.F. \( = e^{\int \frac{2}{x}dx} = e^{2\ln x} = x^2. \)

Step 5: Multiply through by \( x^2 \): \( x^2\dfrac{dz}{dx} + 2xz = -2x^4. \)

LHS = \( \dfrac{d}{dx}(x^2z) = -2x^4. \)

Integrate both sides: \( x^2z = -\dfrac{2x^5}{5} + C. \)

\( z = -\dfrac{2x^3}{5} + \dfrac{C}{x^2}. \)

Step 6: Substitute \( z = y^{-2} \): \( \boxed{y^{-2} = -\dfrac{2x^3}{5} + \dfrac{C}{x^2}.} \)

Applications of Differential Equations — Growth and Decay, Newton’s Law of Cooling, and Motion Problems

Differential equations are used to model many real-life physical and natural processes, such as population growth, radioactive decay, cooling of objects, and motion under gravity. Each of these processes is governed by the rate of change of a quantity with respect to time or another variable.

Exponential Growth and Decay

When the rate of change of a quantity is proportional to the quantity itself, the process follows exponential growth or decay.

$ \dfrac{dy}{dt} = ky $

where:

- \( y \): the quantity at time \( t \)

- \( k \): proportionality constant

Solution:

$ \int \dfrac{dy}{y} = \int k\,dt \Rightarrow \ln y = kt + C \Rightarrow y = Ae^{kt} $

- If \( k > 0 \), exponential growth.

- If \( k < 0 \), exponential decay.

Example

A bacteria population doubles in 3 hours. If the initial population is 500, find the population after 9 hours.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Let \( y \) be the population at time \( t \).

\( \dfrac{dy}{dt} = ky \Rightarrow y = Ae^{kt}. \)

At \( t = 0, y = 500 \Rightarrow A = 500. \)

At \( t = 3, y = 1000 \Rightarrow 1000 = 500e^{3k} \Rightarrow e^{3k} = 2 \Rightarrow k = \dfrac{\ln 2}{3}. \)

At \( t = 9 \): \( y = 500e^{9k} = 500e^{3(\ln 2)} = 500(2^3) = 4000. \)

Answer: Population after 9 hours = 4000.

Radioactive Decay

In radioactive decay, the rate of disintegration of nuclei is proportional to the amount of undecayed material present at that moment.

$ \dfrac{dN}{dt} = -\lambda N $

where \( \lambda \) is the decay constant.

Solution:

$ N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} $

- \( N_0 \): initial amount of substance

- \( N \): remaining amount after time \( t \)

Example

A radioactive substance loses 20% of its mass in 5 years. Find its half-life.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Given: \( N = 0.8N_0 \) when \( t = 5. \)

\( N = N_0 e^{-\lambda t} \Rightarrow 0.8 = e^{-5\lambda}. \)

Taking logs: \( \lambda = -\dfrac{1}{5}\ln(0.8) = 0.0446. \)

For half-life \( T \), \( N = \dfrac{N_0}{2} \): \( \dfrac{1}{2} = e^{-\lambda T} \Rightarrow T = \dfrac{\ln 2}{\lambda} = \dfrac{0.693}{0.0446} \approx 15.54 \text{ years.} \)

Answer: Half-life ≈ 15.5 years.

Newton’s Law of Cooling

The rate of change of temperature of a body is proportional to the difference between its temperature and the surrounding temperature.

$ \dfrac{dT}{dt} = -k(T – T_s) $

where:

- \( T \): temperature of the body at time \( t \)

- \( T_s \): surrounding temperature (constant)

- \( k \): positive constant

Solution:

$ T – T_s = (T_0 – T_s)e^{-kt} $

where \( T_0 \) is the initial temperature of the body.

Example

The temperature of a body cools from \( 80^\circ C \) to \( 60^\circ C \) in 10 minutes, when the surrounding temperature is \( 20^\circ C \). Find the temperature after 20 minutes.

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Using \( T – 20 = (80 – 20)e^{-kt} \Rightarrow T – 20 = 60e^{-kt}. \)

At \( t = 10, T = 60 \): \( 60 – 20 = 60e^{-10k} \Rightarrow 40 = 60e^{-10k} \Rightarrow e^{-10k} = \dfrac{2}{3}. \)

\( k = \dfrac{1}{10}\ln\dfrac{3}{2} = 0.04055. \)

At \( t = 20 \): \( T – 20 = 60e^{-20k} = 60e^{-0.811} = 60(0.445) = 26.7. \)

Temperature after 20 min: \( T = 46.7^\circ C. \)

Motion Problems — Velocity and Acceleration

If the rate of change of velocity (acceleration) depends on velocity or position, it can often be modeled as a differential equation.

Example forms:

- \( \dfrac{dv}{dt} = k(v_t – v) \) — approach to terminal velocity

- \( \dfrac{dv}{dt} = -kv \) — resistive medium (exponential decay in velocity)

Example

A particle falling under gravity experiences air resistance proportional to its velocity. If its terminal velocity is \( 50 \, \text{m/s} \), find its velocity after 5 s. Assume \( g = 10 \, \text{m/s}^2. \)

▶️ Answer / Explanation

Equation of motion: \( \dfrac{dv}{dt} = g – kv. \)

At terminal velocity, \( \dfrac{dv}{dt} = 0 \Rightarrow g = kv_t \Rightarrow k = \dfrac{g}{v_t} = \dfrac{10}{50} = 0.2. \)

\( \Rightarrow \dfrac{dv}{dt} = 10 – 0.2v. \)

Integrate using separable variables:

\( \int \dfrac{dv}{10 – 0.2v} = \int dt. \)

\( -5\ln|10 – 0.2v| = t + C. \)

At \( t = 0, v = 0 \): \( -5\ln 10 = C. \)

At \( t = 5 \): \( -5\ln|10 – 0.2v| = 5 – 5\ln 10 \Rightarrow \ln|10 – 0.2v| = -1 + \ln 10. \)

\( 10 – 0.2v = 10e^{-1} \Rightarrow v = 50(1 – e^{-1}) \approx 31.6 \, \text{m/s}. \)

Answer: Velocity after 5 s = 31.6 m/s.