Questions 43–52 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from Ed Yong, “Why We Sleep Badly on Our First Night in a New Place.” ©2018 by The Atlantic Monthly Group.

When you check into a hotel room or stay with a friend, is your first night of sleep disturbed? Do you toss and turn, mind strangely alert, unable to shut down in the usual way? If so, you’re in good company. Line 5 This phenomenon is called the first-night effect, and scientists have known about it for over 50 years. “Even when you look at young and healthy people without chronic sleep problems, 99 percent of the time they show this first-night effect—this weird half-awake, Line 10 half-asleep state,” says Yuka Sasaki from Brown University. Other animals can straddle the boundaries between sleeping and wakefulness. Whales, dolphins, and many birds can sleep with just one half of their brains Line 15 at a time, while the other half stays awake and its corresponding eye stays open. In this way, a bottlenose dolphin can stay awake and alert for at least five days straight, and possibly many more. Sasaki wondered if humans do something similar, Line 20 albeit to a less dramatic degree. Maybe when we enter a new environment, one half of our brain stays more awake than the other, so we can better respond to unusual sounds or smells or signs of danger. Maybe our first night in a new place is disturbed because half Line 25 our brain is pulling an extra shift as a night watchman. “It was a bit of a hunch; she says. “Maybe we’d find something interesting.” She invited 11 volunteers to spend a few nights at her laboratory. They slept in a hulking medical scanner Line 30 that measured their brain activity, while electrodes on their heads and hands measured their brain waves, eye movements, heart rate, and more. While they snoozed, team members Masako Tamaki and Ji Won Bang measured their slow-wave Line 35 activity—a slow and synchronous pulsing of neurons that’s associated with deep sleep. They found that this slow activity was significantly weaker in the left half of the volunteers’ brains, but only on their first night. And the stronger this asymmetry, the longer the volunteers Line 4o took to fall asleep. The team didn’t find this slow-wave asymmetry over the entire left hemisphere. It wasn’t noticeable in regions involved in vision, movement, or attention. Instead, it only affected the default mode Line 45 network—a group of brain regions that’s associated with spontaneous unfocused mental activity, like daydreaming or mind-wandering. These results fit with the idea of the first-night brain as a night watchman, in which the left default mode network is more Line 50 responsive than usual. To test this idea, Sasaki asked more volunteers to sleep in a normal bed with a pair of headphones. Throughout the sessions, the team piped small beeps into one ear or the other, either steadily or Line 55 infrequently. They found that the participants left hemispheres (but not the right) were more responsive to the infrequent beeps (but not the steady ones) on the first night (but not the second). The recruits were also better and quicker at waking up in response to the Line 60 beeps when the sounds were processed by their left hemispheres. This shows how dynamic sleep can be, and how attuned it is to the environment. The same applies to many animals. In 1999, Niels Rattenborg from the Max Line 65 Planck Institute for Ornithology found that ducks at the edge of a flock sleep more asymmetrically than those in the safer center. “In this way, sleeping ducks avoid becoming sitting ducks; he says. Lino Nobili from Niguarda Hospital in Milan adds Line 70 that these results fit with a “relatively new view of sleep” as a patchwork process, rather than a global one that involves the whole brain. Recent studies suggest that some parts can sleep more deeply than others, or even temporarily wake up. This might explain not only Line 75 the first-night effect but also other weird phenomena like sleepwalking or paradoxical insomnia, where people think they’re getting much less sleep than they actually are. To confirm the night watch hypothesis, Sasaki now Line 80 wants to use weak electric currents to shut down the left default mode network to see if people sleep faster in new environments. That would certainly support her idea that this region is behind the first night effect. It won’t help people sleep better in new places, Line 85 though. To do that, Sasaki tries to stay in the same hotel when she travels, or at least in the same chain. “I’m flying to England tomorrow and staying at a Marriott,” she says. “It’s not a completely novel environment, so maybe my brain will be a little more so Line 90 at ease. Mean Brain Response to Deviant Sounds during Slow-ware Sleep Response to Deviant Sounds during Slow-ware Sleep over Time

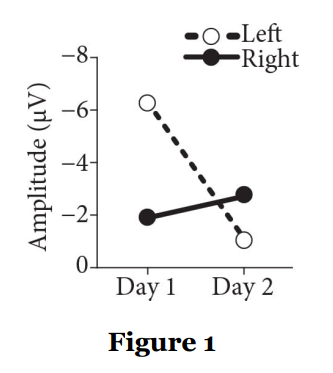

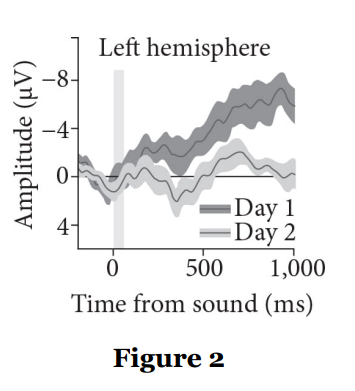

Response to Deviant Sounds during Slow-ware Sleep over Time

43. The primary purpose of the passage is to

- describe a study on how slow-wave sleep activity causes sleep disorders.

- analyze the neural underpinnings of slow-wave sleep activity.

- propose solutions for difficulties sleeping in new places.

- discuss research on a common phenomenon in sleep.

Ans:/Explanation

Ans:D

44. In the third paragraph (lines 19–27), the author uses the words “wondered” and “hunch” primarily to suggest that Sasaki and her colleagues

- believed that the first-night effect would be most apparent in people who had greater awareness of their surroundings when going to sleep.

- had not previously discovered evidence that part of the human brain responds to environmental stimuli when sleeping in a new place.

- questioned whether the link between animal sleep patterns and the first-night effect in humans was related to similarities in their environment.

- did not predict that slow-wave brain activity would have such a great influence on quality of sleep in various locations.

Ans:/Explanation

Ans:B

45. Which statement regarding subjects who had weaker left hemisphere slow-wave activity during the first night in the medical scanner can be most reasonably inferred from the passage?

- They are more wakeful when presented with environmental stimuli while sleeping in a new place.

- They are more restless sleepers overall and have trouble falling asleep in places other than their homes.

- They are more likely to suffer from afflictions such as sleepwalking or paradoxical insomnia.

- They are not able to sleep through the night unless their surroundings are silent.

Ans:/Explanation

Ans:A

46. Which choice provides the best evidence for the answer to the previous question?

- Lines 38–40 (“And the…asleep”)

- Lines 58–61 (“The recruits…hemispheres”)

- Lines 74–78 (“This…are”)

- Lines 79–82 (“To confirm…environments”)

Ans:/Explanation

Ans:A